Introduction

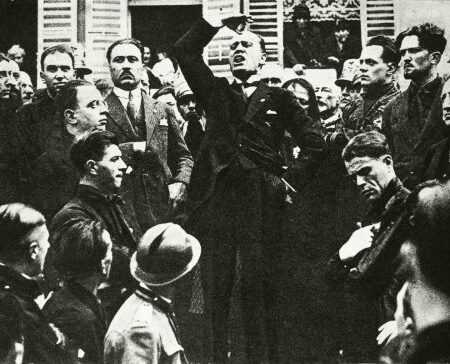

The 20th century is the century of two world wars, and authoritarian regimes such as the Soviet Union, Nazi Germany, and Fascist Italy. The main reason for the rise of these regimes had to do with the ways their ideologies completely penetrated the underlying societies and the strengthening of these dictatorships’ political influence.

In this century, the Soviet Union was born and collapsed, a regime which included 15 countries and was one of the most powerful states of its time. However, in order to maintain its strength and ensure internal order, the Soviet government needed to deploy powerful propaganda in the fraternal countries.[1] In my final project, I am conducting a study of the influence of Soviet propaganda on public behaviors, cultural values and traditions of Soviet citizens, using the example of the Uzbek SSR and, more specifically, the city of Tashkent, because the latter was the capital of this SSR.

My time frame for this work will be the period between 1925 and 1950, since it was during this period – namely in 1924 – that the Uzbek SSR’s territorial delimitation took place. Additionally, propaganda work was carried out through the whole time frame I have chosen. This time frame also includes the important period of the Great Patriotic War (1941-1945), and related motivational slogans and propaganda for the people of Uzbekistan, clearly demonstrating how propaganda was a tool to motivate people and contributed to the rallying of the population of Tashkent for this war effort. For example, I look at the family of the blacksmith Shomakhmudov, a man who adopted 15 children from all countries of the Soviet Union and was hence turned into a propaganda tool.

Also in my project, I will give examples from real propaganda sources used by the Soviet regime. Additionally, though the use of various sources, including interviews with people who personally lived in the Soviet Union, I give a clear idea of life in that era for the inhabitants of the city of Tashkent. I also tried to get information about the real conditions of life and public education from the lips of people of various professions who lived at that time. My project can give new information about the nature of Soviet propaganda in the Uzbek SSR, detailing how an extensive and constant propaganda effort was required, to appease the nationalist feelings of patriotic sections of the general population and, in particular, the intelligentsia that encouraged people to restore the old traditional order.

The Use of Propaganda to strengthen the Regime

In the period after the annexation of the territories of the Emirate of Bukhara, the Kokand Khanate and the Kharezm Khanate, a territorial delimitation was carried out and the Uzbek SSR was founded. On the territory of the Uzbek SSR, Tashkent was the capital. And the government was a Soviet one. People lived in a new country, and the first thing the regime had to do was to strengthen its power; for this, a special tool was needed, namely strong propaganda.

The need to indoctrinate residents of Tashkent also entailed the extensive use of propaganda both in public communication and in the educational environment, where the Soviet system and the policy of socialism were fully glorified. The use of propaganda increased when the regime felt it was vital for its survival, such as when World War II broke out or some nationalist movements took off. On the other hand, the use of propaganda decreased in very stable political contexts. In general terms, a totalitarian form of government was founded and freedom of speech was eliminated, while people were forced to inform on each other and often were arrested for deeds committed against the regime. At times, these opponents of communism were liquidated or otherwise repressed. [2]

Public Perceptions of Propaganda

Over time, the regime in the country became stronger, the regime’s authority in the eyes of the people only grew, and, as a result of the abolition of the old order and the introduction of the ideology of Marxism and Leninism to the masses, propaganda was also introduced into the official educational environment.

Naturally, in Tashkent this propaganda bore fruit over time. And the citizens of Tashkent gradually began to support the regime. In particular, when the Second World War broke out, under the slogans of the Socialist leadership, the people of Tashkent rallied to the cause and eventually the Uzbek SSR contributed to the survival of the USSR by acting as a raw material base during the Second World War. And after the victory over the invaders, the Uzbek SSR needed a hero and it chose the poor blacksmith Shomakhmudov, who managed to adopt 15 children during the war. The dictatorship began to promote him as an illustrious example of the brotherhood of peoples and love for communist comrades. Regime propagandists wrote about him, and he was portrayed in Tashkent as an outstanding example of a Soviet person. A monument was erected to him and his adopted children in the center of the capital, which still stands and vividly shows the ideological atmosphere of that time.

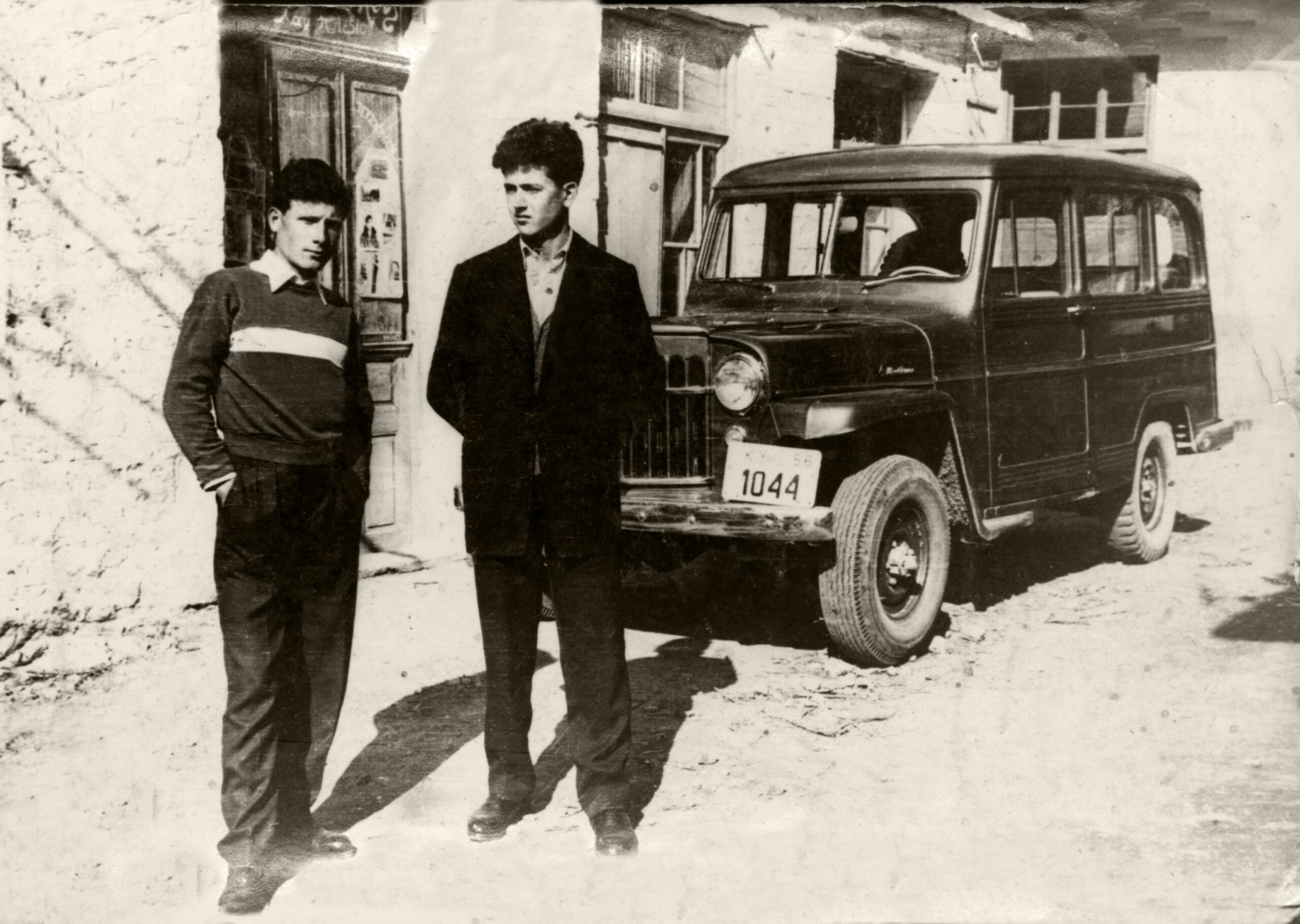

To ascertain the motives that compelled the blacksmith Shomakhmudov to adopt 15 children, despite being poor, and to understand more clearly the influence of propaganda over such a decision, I interviewed Olga Nikolaevna, a neighbor of the Shomakhmudov family, who lived in a house opposite this family. I asked her about the possible reasons the blacksmith adopted the children. Her answer highlights the blacksmith’s attachment to the Soviet polity.

Also, in order to survey the influence of propaganda on the whole population of Tashkent, I interviewed representatives of various professions in the Soviet regime who, in one way or another, experienced the propaganda of the regime, living in Tashkent under the control of the communist Party. I did a short interview with a professor of History at a Soviet educational institution, Saida Burieva. My main question concerned her opinion about life in the Uzbek SSR – the city of Tashkent in particular – and people’s feelings about Bolshevik rule. She briefly answered that propaganda messages were fully accepted by sectors of the people of Tashkent.

At the same time, I would claim that the following two interviews highlight that there were limits to the successful penetration of propaganda within the capital’s society, as both of the related interviewees – a veteran who served in the Soviet army, Khairulla Eshkabilov, and Elnora Siddikova, who was a primary school teacher in Tashkent and witnessed the use of propaganda in the educational system – mention there was some discontent with the regime. I asked Eshkabilov questions about Soviet public communication’s influence over the people and whether there was any fear among them regarding the policy of the Bolsheviks.

As for Siddikova, I asked her about her experience acquainting students with political materials of the Soviet Union and the types of propaganda that were carried out in schools.

Finally, I did an interview with Mirjon Khamraev, who was a simple proletarian worker in Tashkent, and I tried to find out about the working conditions for ordinary workers, and the pros and cons of life under the communist dictatorship according to him. In particular, I asked him about political indoctrination carried out among the workers of his plant and whether he lived better in the Soviet period or now.

In the end, taking into account my interviews and various historical events, I want to say that the propaganda carried out in Tashkent was successful on the whole, as it convinced the majority of the population of Tashkent to comply with the communist regime. However, a certain segment of the population would not cooperate with this regime, ending up persecuted by the latter, as the dictatorship was denoted by a repressive and intolerant attitude towards other ideologies, traditions and values. In general, people in Tashkent who survived the Soviet Union speak well of it, but there are also those who fell victim to persecution and repression by this dictatorship. Propaganda for sure played a key role in the strengthening of the regime. However, it was not just the extensive use of this tool, but also other developments, such as the outbreak of World War II, which strengthened, in the minds of citizens of Tashkent, the belief in the need to support Bolshevik policy.

Conclusion

It might be said that, in order to win the loyalty of the Tashkent people, the leadership of the USSR strove to provide this population with a stable life, a developed economy, and a sense of national might and cohesion. To inculcate the image of a strong country and powerful ideology in the citizens of Tashkent, pupils in schools were taught the ideology of the Soviet government, and they and other individuals were further instilled this image through the public dissemination of daily news. Depending on the situation, the use of propaganda intensified or was stable. Ordinary hard workers from the countries of the USSR were taken as an example of heroes and shown as an example of an ideal Soviet person. Blacksmith Shomahmudov is an example of this pattern.

Generally, the people who lived in Tashkent had an ambiguous attitude towards the regime, as attested by the fact that people espousing other ideologies were persecuted. At the same time, propaganda influenced most people and, on the whole, was partially successful, as indicated by the fact that to this day some people still think back to those times with a positive attitude. Based on this, we might say that indoctrination worked on many Tashkent dwellers, but for those who suffered most severely from the regime’s policies, it did not. In general terms, people held different views of the regime. I believe that propaganda, albeit in part, helped to penetrate the political border separating citizens of Tahskent from the regime, and a large part of the population became loyal to the dictatorship. But I must clarify that the propaganda alone could not secure the support of the people of Tashkent for communism. Only when combined with other tools, such as repression and economic incentives, it ended up being successful.

[1] Kamariddin Usmanov “ History of Uzbekistan ( Tashkent Press, 2007), 279-294.

[2] Kamariddin Usmanov “ History of Uzbekistan ( Tashkent Press 2007), 267-271.

[3] Interview with Olga Nikolaevna, author: Akhmadov Sh., Tashkent, 08/04/22

[4] Interview with Saida Burieva, author: Akhmadov Sh., Tashkent, 20/03/22

[5] Interview with Khayrulla Eshkabilov, author: Akhmadov Sh., Tashkent 30/05/22

[6] Interview with Elnora Siddikova, author : Akhmadov Sh., Tashkent 15/05/22

[7] Interview with Mirjon Khamraev, author: Akhmadov Sh., Tashkent 30/05/22

Bibliography

Academy of Sciences of the Republic of Uzbekistan : https://www.academy.uz/uz/news/ozbekiston-tarixi-1917-1991-yillar-kitobi-chop-etildi

The website is about the Soviet Socialist Republic of Uzbekistan:

https://qomus.info/oz/encyclopedia/ou/ozbekiston-sovet-sotsialistik-respublikasi/

K.Usmanov “History of Uzbekistan”( Tashkent Press,2007)