ALBANIA 1975 -1991

During the final phase of the Cold War (1975 – 1991), Soviet Union (SU) began to open to the West. All Eastern Bloc countries followed faithfully Russia’s lead. There was, however, one exception, as with any rule: Albania.

Albania was a war-torn country with numerous internal flaws and economic shortcomings. In

1945, communism was established in Albania under the leadership of Enver Hoxha (1908 -1985,

Premier of Albania from 1945-1985).The state’s relations with the Soviet Union and other

communist countries were initially cooperative and mutually beneficial.

In detail, using the loans given to it, Albania managed to rebuild itself. Within twenty years, the

country began to produce bread and other foodstuffs, generate its energy, and establish an

education system capable of reducing the illiteracy of its citizens. Meanwhile, Albania had

expanded its commercial relations with the Eastern bloc and built its status as a country.

However, in 1960, the Soviet Union was dissatisfied with the way the country used its loans.

Hoxha, on the other hand, blamed the Soviets for the country’s continued capitalization and

conversion to the West. Therefore, Albania shifted its focus to China and began trading with it

exclusively. Nonetheless, the relationship ended, again, violently. The alliance’s impasse,

combined with the opening of China to the West, prompted the government to reconsider its

position as China’s most devoted European ally.

Albania was completely cut off from all potential allies. Specifically, Hoxha closed every

communication outlet with the outside world. No one could cross the Albanian border without

an official license by the state. Furthermore, all trading relations with the SU and China were

stopped, leading gradually to a lack of supplies. This total estrangement of the country from the rest of the world had a significant impact on his foreign and domestic policy from 1975 to 1985 1.

According to Hoxha and the Communist Party of Albania (the CPA), the SU and the West sought to destroy Lenin and Marx’s legacies in order to establish a world based on capitalism and ruthlessness. Fearing the influence of these changes in the Eastern Bloc and Albania, Hoxha and his colleagues oversaw a policy which promoted xenophobic nationalism, ideological dogmatism, personal survival concerns, and Albania’s absolute autonomy 2. To carry out this plan, four tools were used: propaganda, oppression, harsh authoritarianism and nationalism.

While the rest of the Eastern Bloc opened up, Albania closed down even more and remained an authoritarian regime influenced by Stalin’s doctrine of the 1950’s. The state had complete

control over all aspects of life and imposed rigid punishments. Anyone who opposed or was

suspected of opposing the system was exiled with his family or sent to prison. Collective

responsibility was one of the regime’s main doctrines, claiming that if a family member was

found guilty, the entire family was exiled. No one could leave Albania, no one could express a

different political point of view and no one could protest against the existing order.

WHY STUDYING THE CASE OF ALBANIA?

I grew up in a family where everyone was born and raised in this system. Since I can remember

myself, one of the most common topics in family discussions was life in communist Albania.

Most conversations, however, were general, and no one mentioned their feelings about the

regime.

Therefore, my interest in the honest impression of people who experienced this regime grew.

Specifically, most of the information available concerns the structure of the system and

subsequent expert analyses, but few contain firsthand accounts by the people of the time 3 4.

Having this in mind and the fact that for forty years, the communist system of Albania remained

powerful, I decided to study this case, which many compare to today’s North Korea 5. Did people

align with the state’s politics and ideology, or did they obey passively to guarantee their safety

under the authoritarianism of the time?

Thus, the following essay attempts to focus on the way that people perceived their life then and to understand whether and to what extent authoritarianism and isolation could result in an

impassive and de-ideological society.

In search of researching the above, I discussed with my family members, who lived in this

period and can give an insight about life in Albania from 1975 to 1991. Each had something

unique to contribute to the research since he witnessed the regime’s oppression from a

different perspective. During this decade, my parents, Ermir Maranaku and Dhurata Mema were

children. My aunts, Irma Mema and Vera Derstila were in their late teens, and my uncles, Arben

Zeneli and Albert Derstila were in their early twenties.

THE PERIOD OF COMPLETE OPPRESION: 1975 -1985

As previously stated, the decade between 1975 and 1985 was marked by widespread oppression and autarchy.

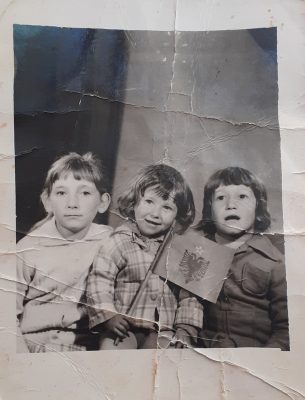

The Μema sisters on the day of the national holiday, November 29, when the liberation of the country from the Nazi army is celebrated.

It all started from younger ages. Education was always a top priority in totalitarian Albania.

More specifically, the educational system was organized in a way that schools could be a tool for keeping society under control. It is well known that all upheavals and changes start from youth.

When a regime manages to subdue the spontaneous nature of young people, it can then

dominate better the society as a whole. Thus, all lessons were designed with an effort to instill

hostility toward imported bourgeois and western cultural traditions. The pure temperament of

children was used by the state to impregnate subconsciously within them the importance of

protecting the Party and, in particular, their homeland from exogenous potential enemies. 6. Example of the cultivation of nationalism is that all kids “gathered in the yard before going into the classes and recited in unison: “Pioneers of Enver! We are ready anytime for the well-being of the Party” as Vera recalls.

Anyone can surmise that manipulation did not stop in the classroom. Instead, regulations were

enforced everywhere. People had few options for what music they listened to, movies they

watched, and clothes they wore. More specifically, music focused on traditional songs and

classical music, films were mostly Albanian-made, and clothing was specific. Short skirts, bell-

bottom jeans, and long hair were strictly prohibited. “Nothing should be overwhelming or

eccentric, you could not stand out,” Arben says.

This demonization of differentiation was a trait that permeated all of society. The movements,

style, words, and behaviors of the people were constantly monitored. Anyone who deviated

even slightly from the norm was prosecuted as a traitor.

In particular, the government had established a secret police force, the Sigurimi 7, comprised of undercover policemen who controlled clandestinely the movements of people. The Sigurimi were tasked with eliminating all forms of opposition. If someone said something against the state’s policy, or disobeyed the laws became a direct target.

“The fact that you didn’t know them made them even scarier,” Irma continues. “My father, even

though he traveled and had seen some other countries of Eastern Block due to his work, he had never told us anything. When I asked him how was life abroad, he replied, “Fine! It’s ok! They live as we do.”

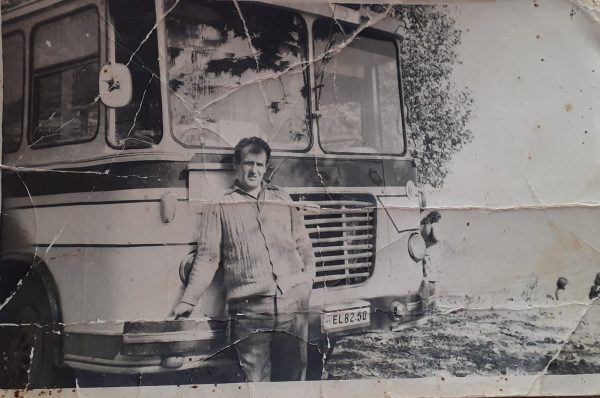

During this time, only truck and bus drivers and special envoys were permitted to cross the border. Everyone was given strict instructions and was not allowed to share any information or experiences from their travels.

Such reactions demonstrate how fear was implanted in the people’s lives. Being unable to speak

openly in your home is a strong indicator that people were constantly on the defensive and on high alert. Every action was carefully considered, because even a single wrong word could send an entire family into exile or prison.

Thus, social relationships were based on suspicion, skepticism, and mistrust. “There was a law

that anyone who spoke out against the system was arrested,” Albert says. “Many people were eager to spy on one another. This was done either to make a decent impression on the Party or to profit from it. Many were ready to betray you for the smallest thing. Among 3 people the 2 were spies. The culture of spying had become part of the society’s identity,” Ermir highlights. The eagerness to maintain a “proper”- according to state’s point of view- behavior had a negative impact both on a personal and social level in Albania.

Consequently, everyone was just trying to safeguard themselves and their family. “We just

minded our business and tried to live peacefully. There were no other options. Either you supported and defended the Party, or you would be persecuted” Irma emphasizes.

Even though the above situation is unbelievable, the most shocking aspect is the lack of personal aspirations and future dreams that characterized this period. In particular, when discussing with someone about their youth, one expects them to communicate their dreams, aspirations, and desire to explore the world. This, however, did not occur in the aforementioned interviews.

“I imagined a simple life as a teacher. After high school, you would apply to university. In this

application, you could only declare three options. For instance, in my application, my first

preference was Albanian language and history, my second was Albanian language and literature, and my third was “wherever my country needs me.” We were forced to have this third option”, Irma claims.

“Consider leaving? No way! Firstly, it was illegal. Secondly, we were raised to believe that there was no such place as Albania. We had no intention of going abroad. We had no idea what it meant to leave the country,” Vera emphasizes.

Looking closer, one can see a group of young people who were unable to dream. Despite being of different ages, they all have the same point of view: one that is restricted in what they were permitted to do. The system was created in a way that the necessities of the state came first. Personal needs and desires were frequently silenced as eccentric or opposed to the common good. The choice to follow a different route did not exist. No one could leave Albania, no one could protest against the regime and no one could dare to dream changing the existing order.

THE YEARS OF SLOW CHANGE: 1985 -1990

These were the most decisive five years in the history of communist Albania. Signs of change started to appear in Albania because of Hoxha’s death, economic instability, and the sociopolitical rearrangements that rocked the Eastern Bloc.

The beginning of the end of this regime was Hoxha’s death, on April 11, 1985 8 . “It came as a complete surprise to us. We didn’t hear anything from him at the time. He had been isolated in his home for a long time” Ermir stated.

“I cried a lot. I was saddened to see Hoxha’s funeral on television. I recall many of my classmates crying as well. It was a devastating blow to me. I was insecure and disoriented. I wasn’t sure if there would be someone better than him to lead us.” -Dhurata Mema (then a primary school student)

On the other hand, many claim that the sadness was not that real:

“People felt compelled to express their grief and cry over Hoxha. People needed to keep their jobs,

so they took photos with Hoxha’s photos and cried. All visits to his grave were planned; they didn’t

go there with their willingness. It was a way for them to secure their future while the system

crumbled. They had no choice but to conform to the norms of the time,” Arben says.

Meanwhile, the state’s economic instability exacerbated the country’s political shift. In

particular, since 1983, the country has been dealing with food shortages and economic

difficulties which made survival more difficult. “We had several shortcomings. I would get up in

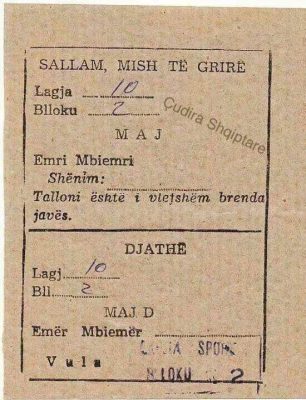

the morning and stand in line for milk. There were times when I did not take it because the stocks were insufficient. Later they gave us some coupons so everyone could get some food.” Ermir underlings.

shift in Albanian society due to the country’s dire financial situation. Consequently, the Party

demonstrated greater tolerance. “Until 1983, we only heard and told what we were supposed to

hear and say. The Party filtered our knowledge of the world. But from there, we began to learn more from abroad and talk a bit more openly. Also, people began to flee and seek asylum in European countries,” Arben explains.

Adding to the above the changes that occurred in the Eastern Block from 1989, one can guess

that Albanian society was somehow starting to feel the upcoming change. “We knew the end

was approaching. The transformation had begun,” says Albert.

THE FALL OF COMMUNIST ALBANIA: 1991

The year of transition arrived. From one day to the next, communist Albania morphed into a

capitalist state. Questioning the regime turned into upheavals. The culmination happened on

February 20, when students in Tirana unearthed the statue of Hoxha 12 . This was a symbol of reaction to oppression. “It was strange. There was a sense of unease,” Arben admits. “Despite the upheavals, there was no bloodshed. However, the fact that the change occurred overnight created social unrest and insecurity that we had never known before,” Ermir remembers.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Jv9bYYorKGo

The fall of communism appeared to be a catalyst for Albanian society. For the first time,

Albanians realized the oppression they had endured and were free to express their aversion to

it. People voiced their desire for change. That year was not a triumph of capitalism over communism, but of liberty over oppression.

The system’s downfall came at a high socioeconomic cost.

“In a single day, thousands of people lost their jobs, many government-run factories closed, and many of our people left. We had no idea what the future held, but we knew Albania needed a change.” – Albert Derstila

The need for survival led many people to migrate. One of them was Arben, who traveled to

Italy. “Albania was in deep trouble. The system shifted abruptly and dramatically. We didn’t have time to adjust. So I made the decision to leave. I traveled to Italy aboard the largest ship at the time. When I arrived, I noticed a significant difference. It was different from what I was used to. People in Italy owned their homes and cars. We didn’t have cars in Albania! The stores were brimming with goods. I went to Italy to work and make a better life for myself. I didn’t go there to do politics. I needed a job so that I could send money back to Elbasan. If I had to travel there and sit, I would prefer Albania. I arrived and immediately began working hard. I had a family in Albania, but I had to leave to survive,” Arben recalls.

behind. However, the situation in Albania was intolerable at the time. The economy and living

standards were at their lowest points. These people who left in 1991 and 1997-1998 were

looking for a better life and a higher standard of living. The only way to a better life was leaving

the country.

CONCLUSIONS

As someone who has never experienced such a regime, I often found it challenging to

comprehend the emotions and stories that surfaced. Also, it was difficult for me to draw any

firm or even speculative conclusions. I gathered information from only six people who come

from various backgrounds. Therefore, their testimonies may have been indirectly influenced by

their later experiences, their social status, or even sometimes by the passage of time.

Despite all the difficulties, reading the words of the above people, allows one to draw some,

even individualized, conclusions about life in communist Albania. Initially, the people did not appear to have any powerful communist consciousness, as depicted by the Media of the period.

On the contrary, a part of society seemed to be de-ideologized. Furthermore, the people’s main concern has been mostly survival within a regime that could turn against them at any time. The constant danger had a catalytic effect on people’s actions. In particular, the main concern was not to provoke and ensure their livelihood, safety, and self-interest. Lastly, it seems that authoritarianism and the absence of a measure of comparison somehow managed to nurture people’s apathetic nature. As long as one managed to create a safe life according to the system’s rules, there was no room for claiming to change or improve his life. People learned to live one reality: to be safe.

This reality, which limited citizens’ ability to act and develop, is reflected strongly in how the people of that generation still define themselves: “We are indeed a lost generation.“, Ermir, Arben and Albert highlight.

All of the above is nothing more than fodder for further discussion and thought. Beyond the way of viewing the past, it is essential to observe how and to what extent this oppression affected the choices and character of people when they finally were free to choose their lives.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

- Cook, Bernard A. Europe Since 1945: An Encyclopedia. London: I.B.Tauris, 2001.

- Fevziu, Blendi. Enver Hoxha: The Iron Fist of Albania. London: I.B.Tauris, 2016.

- Idrizi, Idrit. “Experiencing and Privately Remembering Late Albanian Socialism: A Study Based on Oral History Interviews in the Region of Shkodra.” Mediterranean Journal of Social Sciences, Vol 8, No 5, (2017).

- Mullahi, Anila, and Dhimitri, Jostina. “Educational Issues in Totalitarian state (case of Albania).” Procedia – Social and Behavioral Sciences, 174 (2015).

- Vickers, Miranda. The Albanians: A Modern History. London: I.B.Tauris, 1995.

- Woodcock, Shannon. Life is War: Surviving Dictatorship in Communist Albania. Chicago: HammerOn Press, 2016.

INTERVIEWS

- MARANAKU ERMIR, 12/04/2022, ATHENS, GREECE

- MEMA DHURATA, 14/04/2022, ATHENS, GREECE

- ZENELI ARBEN, 17/04/2022, VERONA, ITALY (through skype)

- MEMA IRMA, 17/04/2022, VERONA, ITALY (through skype)

- DERSTILA ALBERT, 25/04/2022, ELBASAN, ALBANIA (through skype)

- MEMA DERSTILA VERA, 25/04/2022, ELBASAN, ALBANIA (through skype)

*The featured image for this project comes from Mud Sweeter Than Honey: Voices of Communist Albania by Margo Rejmer (New York: Restless Books, 2021). More about the book at https://www.theneweuropean.co.uk/communism-albania-margo-rejmer/

- Miranda Vickers, The Albanians: A Modern History ( London: I.B.Tauris, 1995), 185-209 ↩

- Bernard A. Cook, Europe Since 1945: An Encyclopedia (London: Routledge, 2001), 104 ↩

- Shannon Woodcock, Life is War: Surviving Dictatorship in Communist Albania. (Chicago: HammerOn Press, 2016) ↩

- Idrit Idrizi, “Experiencing and Privately Remembering Late Albanian Socialism: A Study Based on Oral History Interviews in the Region of Shkodra”, Mediterranean Journal of Social Sciences, Vol 8, No 5, 2017) ↩

- Blendi Fevziu, Enver Hoxha: The Iron Fist of Albania, (London: I.B.Tauris, 2016) 180-215 ↩

- Anila Mullahi and Jostina Dhimitri, “Educational Issues in Totalitarian state (case of Albania)”, Procedia – Social and Behavioral Sciences, 174 2015 ↩

- Bernard A. Cook, Europe Since 1945: An Encyclopedia (London: Routledge, 2001), 106 ↩

- Miranda Vickers, The Albanians: A Modern History ( London: I.B.Tauris, 1995), 210 ↩

- Retro View of Mankind’s Habitat, 16 May 2021, https://pastvu.com/p/1349280, (accessed in July 18, 2022) ↩

- Redaksia Lexo.al, “Ja si ushqeheshin shqiptarët me tollona gjatë komunizit”, June 25, 2018, https://archive.lexo.com.al/foto-ja-si-ushqeheshin-shqiptaret-me-tollona-gjate-komunizit/, (accessed in July 18, 2022) ↩

- Redaksia Lexo.al, “Ja si ushqeheshin shqiptarët me tollona gjatë komunizit”, June 25, 2018, https://archive.lexo.com.al/foto-ja-si-ushqeheshin-shqiptaret-me-tollona-gjate-komunizit/, (accessed in July 18, 2022) ↩

- Miranda Vickers, The Albanians: A Modern History ( London: I.B.Tauris, 1995), 219 ↩

- Italian Archives, “Albanian refugees arriving in Italy, 1991”, rarehistoricalphotos.com, November 27,2021, https://rarehistoricalphotos.com/albanian-refugees-italy-1991/ (accessed in July 15,2022) ↩