Introduction

“As the son of African immigrants, Antetokounmpo was unwelcome in Athens. Then he showed promise as a basketball star”, is a phrase implying the truth about being a black person in Greece.

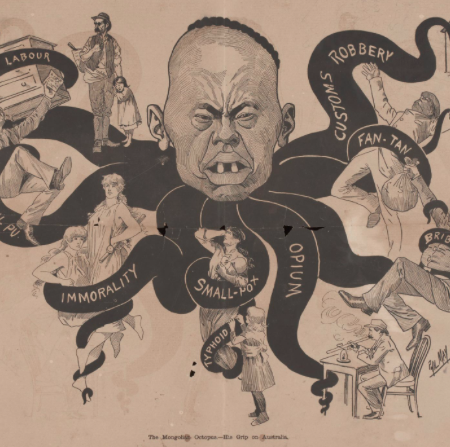

It is widely known that Giannis Antetokounmpo has experienced racism to an intense degree until the moment he became NBA star. He was considered a foreigner and suddenly everything changed. White people in Greece admire his talent and he is officially recognized as a Greek citizen from the state and the public. Being accepted in the NBA brought simultaneously to light the issue of citizenship legislation in Greece. “He was given Greek citizenship in order to prevent him from traveling to New York as a Nigerian,” as Nikos Odubitan claims.[1] The term “Afro-Greek” confers an identity to him, which helped him to be more famous. His story encourages many people of African descent to seek recognition too. Nevertheless, cases like Giannis Antetokounmpo’s do not occur every day, especially when it comes to people who do not have any obvious talent that “attracts” the public interest. Official policy fosters a confusion of identities for people who hail from Africa and live in Greece. The life history of two women will be presented in order to get an insight of how life is in Greece for people of African descent that are not as recognizable as Antetokounmpo.

Research Hypothesis

The Greek state officially recognizes two types of citizens. The first one includes persons who were born and raised in Greece and the second type includes those that were born elsewhere, but grew up in Greece. The second category mostly consists of refugees and immigrants. While Greece Citizenship code offers a clear path for the naturalization of foreign-born persons, the Greek government, unofficially, delays the procedure of granting citizenship to refugees and immigrants and lags behind when it comes to providing intercultural education. Therefore, discrimination against first and second-generation refugees and immigrants, particularly of African descent, is “alive” within Greek society. Despite the difficulties, Afrο-Greek people have already created a solid Greek identity by themselves and are striving to be accepted.

After interviewing two women who came at an early age to Greece from Democratic Republic of the Congo, a different perspective will be presented in this study. Their life histories will give answers and might raise questions about what does it mean to live in a predominantly white, modern, European country.

The interviewees

Fuhayra

The first interviewee was born in 1999 and lived until the age of five in Democratic Republic of the Congo. The current situation in the country became the occasion for her father’s decision to move to Greece for a better life. Democratic Republic of the Congo is considered as one of the “richest” countries in natural sources. This specific fact has become the main cause for political disputes and unfortunately civil wars are often presented as the solution to every problem.[2] The problem of this country is the lack of political will, not of natural resources.[3] The need for a change is obvious as people are leaving Congo and decide to move elsewhere; the population has decreased and those who are staying behind still fight each other.

Specifically, her father was a journalist and during that time it was extremely dangerous to share your opinion to the public, especially about political events. Fuhayra claims: “We left when they started to act in that way to my dad.”

Rebecca

The second narrator was born in 1987 and raised in Democratic Republic of the Congo until the age of ten. She came in Greece without her parents with her two years younger sister and cousin. The three of them lived in an orphanage. She is the daughter of a teacher, who was hoping for a good life and education for the two out of his ten children. The wish of her father was for her to survive in Greece and to learn the language by studying very hard. When she would have grown up enough, she could go back to the country where she comes from and create her life there.

But the memories from her childhood life in Congo were not pleasant: “On one hand, I remember civil wars. The “Great States” were causing issues in order to “do their job”, insidiously. African citizens were fighting each other”.

1. Growing up in Greece as a black person

It is an “irony paradox” to live as a black person in a “self-defined white society”.[4]. Environmental recognition is crucial and the impact on black’s people personality might be different when they are facing phenomena that they have not yet clarified in their minds. Their personality awareness is possible to express itself differently in any occasion. The responses from both interviewees are intriguing when they started to recount their life experiences in Greece as black people. The topics in which they focused most were the school environment, adulthood, entering the labor market and finally the emotional impact their experiences had on them.

1.1 Education

Their answers about how it was to learn a different language were diverse. However, both of them had the same feelings after specific events.

On one hand, Fuhayra narrated the following:

“At the beginning, I was speaking French. The first two years in Greece I was struggling to learn the language”. “I was trying totally alone. Nobody helped me at school”.

Her personality awareness was increased when she had to deal with racism for the first time. She claims:

Fainting ignorance created a safe environment for her. She had never noticed her different skin color until that moment. Being asked that question was the beginning of a journey in “white society” and she was looking for a solution. She eventually decided to choose people who accepted her as she was. She created a great “family of choice” in order to “survive” in Greece, as she claims.

On the other hand, Rebecca’s answer describes a different aspect of being a black student:

“When I went to the orphanage, I met many children in my age. Through playing with other children, especially at the age of ten is definitely easier to speak. There was a teacher, who was giving to us extra help”.

Nevertheless, the phenomenon of racism is similar to her too as Fuhayra:

This specific reaction reveals the “confusion” that society creates. Black people sometimes might not consider themselves as Greeks, even if they are educated and raised in Greece. The reason why this is happening is because they think they do not have “pure” ancestry.[5]

Learning the Greek language was part and parcel of their everyday life. Furthermore, education about the country were growing up in, was extremely important for them. After school was over, Fuhayra had to go home. After her lunch, she spent her time studying, she had the desire to cultivate her intellect. Rebecca adopts this point of view as well. She was going back home after a long day at school and then it was happy “study time”, which also included playing with other children. That was her day, this is what she wanted actually. Both interviewees wanted to learn the language, ethics, traditions and everything else that would give the opportunity to be accepted by their social environment.

1.2 Turning eighteen in Greece

Adulthood as a person who was not born in Greece might make you feel overstressed. These feelings are reflected in the response of Fuhayra:

“When I graduated from High-school, I felt that I was leaving my safe environment. I visualize school as a small society with a control system. In contrast, “the outside world” was not as I was expecting”.

When you turn eighteen in Greece, you are recognized as an adult person. You no longer live in a safe bubble and you have to face reality. You would have to associate with citizens and to deal with the state authorities. Fuhayra had to leave her “family of choice” and to associate with people, who she did not select. Furthermore, there was something that Fuhayra expressed as a “relief”. Acquiring a Greek citizenship document was the chance for her to avoid a huge part of everyday racism phenomena in her adulthood life. More specifically, Greek citizenship acquires mandatory prerequisites governed by the Greek Nationality Code of 1984, which provides citizenship by descent, if one of your parents is a Greek citizen, by declaration, if you have Greek heritage or a Greek adoptive parent, by marriage to a Greek citizen, through investment and, last but not least, by naturalization.

Fuhayra was expecting to get Greek citizenship by naturalization. The whole procedure can be completed after seven years from your move to Greece. Moreover, it is mandatory to speak the language and be knowledgeable about national history and culture.[6] She was always passionate about Greece. Unfortunately, Fuhayra and her family are still waiting for twelve years in order to get Greek citizenship. Bureaucracy was worse than she thought. Moreover, she decided to act in a way that might make her application judged positively; she avoided any contact and connection with her country of origin. This is an unwritten rule. “It is not written anywhere, however you do not have any other choice”.

It is possible that naturalization is not granted to people who are feeling Greeks and they are recognized from the majority of people as a part of the Greek society. In this respect, Rebecca raises the question of whether or not she can be recognized as Greek.

“This issue is very harmful to me. No, I am not a Greek citizen yet. The state asks a specific document from Congo, it is called “birth certificate”, with seals from the Embassy of both countries, located in Congo. My family members did the procedure; they prepared all the documents and the employees at the Embassy did not help them. Specifically, they told them to come back another day and this is what is happening all these years. I realized that I have to deal with it by myself when I will go there. I am 35 years old now and I am not Greek in paper.”

1.3 Entering the Labor market

Interestingly, the narrators also shared their stories about the labor market. In both cases, the conclusion is clear. Working with no full recognition can be a problem. Fuhayra studies Law and she wanted to do her internship. When they saw that she has residence permission, she could easily see people’s facial expressions; they were different than before. Assuming that different skin color is an obvious “disadvantage” for some people, this generates different perspectives. Rebecca’s experience underlines this fact. Specifically, she wanted to find a job and someone was asking for a waitress in a cafeteria. When he saw that she is black he did not hire her. Immediately, her first thought after he said that she is black was “where is the problem? I have values.”

2. Emotions

Each of the storytellers narrated their lives from the moment they came in Greece since now. The novel term “Afro-Greek” showcases their origins, but also their lived experiences all these years and the crucial impact they had on their emotional subjectivity.

Fuhayra has always been a person calling herself Greek. The term “Afro-Greek” conveys a positive meaning for her. It reminds her where she comes from and what she is now. Nobody has used this term to call her up to now. In addition, she claims that she would welcome this term. She knows who she is. According to her, Afro-Greek should be an accepted and better-known term.

Rebecca’s definition indicates the same as well. She wants to go and visit all her family in Congo. She never had the chance. She was always working or did not have enough money to go. Thankfully, they come to visit her in Greece. Living in a European country was one of her dreams. In this way, she is grateful for living in Greece, for learning the history and the language of this country. This is what she knows, this is who she is. The only drawback, she claims, is the issue of recognition from the society. “I do not understand why after all these years…morally I am Greek, what about the documents?” Moreover, talking about the term “Afro-Greek”, her response was positive. She likes Afro-Greek as a term. However, she had never heard it, no one called her like that, but she would like to.[7]

Conclusion

Taking everything into consideration, the participants recognize their selves fully as Greeks. Above and beyond anything else, their identity is absolutely “clear” to them. They know where they were born and where they belong to as well as they know that they have every right to live in Greece without cutting ties with the country where they came from.

Nevertheless, Greek society does not create an amiable, friendly environment; many people do not accept them. Moreover, both narrators have faced racism at least one time in their lives. They got singled out because of their skin color and because of the delaying tactics employed by Greek authorities in order to deny them Greek identification papers. Residence permission is the main document for dealing with the civil service; it provides safety, albeit without acceptance. In addition, the lack of intercultural education also “preserves” the negative attitude of Greek society towards first and second-generation migrants. As a result, creating “a family of choice” of welcoming friends and like-minded acquaintances represents the safest environment for them. Through this specific arrangement, they are not afraid of unfair judgment and preclusion.

Finally, the two narrators would like to live without the fear of being strangers, foreigners in the country where they have been raised and consider their own. There is no confusion of identities to them. “Afro-Greek” should be an acceptable term as a hybrid identity, as a reminder of both where they came from and where do they belong now and, finally, as “a source of comfort” in a society that does not always appreciate difference.

Sources

Blackshire-Belay, C. Aisha. “The African Diaspora in Europe: African Germans Speak Out.” Journal of Black Studies 31, no. 3 (2001): 264–87. http://www.jstor.org/stable/2668033.

Dobbins, James, Laurel E. Miller, Stephanie Pezard, Christopher S. Chivvis, Julie E. Taylor, Keith Crane, Calin Trenkov-Wermuth, and Tewodaj Mengistu. “Democratic Republic of the Congo.” In Overcoming Obstacles to Peace: Local Factors in Nation-Building, 179–204. RAND Corporation, 2013. http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.7249/j.ctt3fgzrv.16.

Goodman, P. S. “Giannis Antetokounmpo Is the Pride of a Greece That Shunned Him” (2019): https://www.nytimes.com/2019/05/03/sports/giannis-antetokounmpo-greece.html

Ministry of Foreign Affairs. https://www.mfa.gr/index.htm

Prunier, G. “Why the Congo Matters.” Atlantic Council, 2016. http://www.jstor.org/stable/resrep03452.

Endnotes

[1] Goodman, P. S. “Giannis Antetokounmpo Is the Pride of a Greece That Shunned Him” (2019): https://www.nytimes.com/2019/05/03/sports/giannis-antetokounmpo-greece.html

[2] Dobbins, James, Laurel E. Miller, Stephanie Pezard, Christopher S. Chivvis, Julie E. Taylor, Keith Crane, Calin Trenkov-Wermuth, and Tewodaj Mengistu. “Democratic Republic of the Congo.” In Overcoming Obstacles to Peace: Local Factors in Nation-Building, 179–204. RAND Corporation, 2013. http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.7249/j.ctt3fgzrv.16.

[3] Prunier, G. “Why the Congo Matters.” Atlantic Council, 2016. http://www.jstor.org/stable/resrep03452.

[4] Blackshire-Belay, C. Aisha. “The African Diaspora in Europe: African Germans Speak Out.” Journal of Black Studies 31, no. 3 (2001): 264–87. http://www.jstor.org/stable/2668033.

[5] Ibid.

[6] For more information, see www.mfa.gr

[7] For efforts to disseminate the term “Afro-Greek” as a means of gaining acceptance, see https://www.facebook.com/menelaoskm/videos/288752285413211/?extid=ID-UNK-UNK-UNK-IOS_GK0T-GK1C-GK2T&ref=sharing