Introduction

Cloth weaving had been in existence from pre-historic times in Nigeria. It came into being when the earliest man discarded the use of leaves and animal skin to cover his nakedness. The bark of certain species of trees formed the material from which the first woven cloth was produced. The barks of the tress were always beaten into fibre, while the fibre was then woven into cloth sometimes Raffia fibre was also woven into cloth though much of it was woven as bags and cotton became of use instead of weaving.1

The Yoruba people are renowned for the production of two types of traditional clothes. It is called traditional because of it is a very long practicing tradition of cloth production of Yoruba people ever before the coming of foreigners whether Muslim merchants or the Christian missionaries. These two clothes production practice include the hand-woven textile called “Aso-Oke/Aso-Ofi” and pattern-dyed cloth called Adire”. The traditional textile art tradition of Yoruba people is an hereditary craft passed from one generation to the other.2 The weaving of Aso-Oke is an old age craft among Nigerians as different groups have local fabrics cherished among the members. More importantly, Aso-Oke is very significant to the Yoruba group of southwestern Nigeria. This is evidenced in its usage in socio-cultural events.3

Aso-Oke is usually worn by Yoruba men and women throughout southwestern Nigeria which basically include contemporary Ekiti, Oyo, Ondo, Osun, Ogun and Lagos State. Yoruba stocks in part of Kwara, Kogi and Edo States and other parts of the countries also wear this kind of cloth. The term Aso-Oke (also known as Aso ofi-both names can be used interchangeable) generally refers to the product from the horizontal loom and cloths made from it.4

The etymology of the name dated back to late 19th century when people of Iseyin Area (Oke Ogun) were referred to by Lagos merchants as “Aso-Oke (people from Oke-Ogun or Yoruba hinterlands). When the cloth made in Iseyin is taken to Lagos for sale, the people in Lagos would called the cloth “Aso awon ara Ilu Oke (cloth of the people from hinterland). It is called Aso-ofi because the process through which it is made, particularly the loom. Aso is the Yoruba name for “cloth” which “ofi” is the loom. Cotton, primary raw materials used in the production of Aso Oke is either locally sourced or imported, although current trends in production adopt the use of synthetic yarns for weaving.5

Common fashion styles often used Aso oke for in Yorubaland was Buba and Iro (top and wrapper), Gele (head gear), Agbada (large gown) and Buba and Sokoto (top and trouser).

Aso oke is a major artifact among the Yoruba and it’s a form of identity that links generation of the Yoruba race. It is a tool for traditional marriages in Yorubaland.6 Although the origin of textiles production and usage in Nigeria, most especially among the Yoruba remain unknown, there are evidences of Yoruba long use of textiles as attire been reflected in ancient sculptures which has been dated back to the 10th and 12th centuries.7

The British policy in Nigeria from 1886 has been said to be designed to knock down the home industries in order to guarantee continuing importation of British made goods on her colonies which Sir Lord Fredrick Lugard implemented. New varieties of cotton introduced during this time, many have been responsible for the large scale production relative to pre-colonial period. Cotton cultivation was promoted in the regions of Yorubaland by the British Cotton Growing Association (BCGA), created in 1902.8 There was huge imposition of tax on the cotton planters and weavers, which made the workers to work harder and earned little profits, because most of the profits have gone into taxes paid to the colonialists through middlemen. Consequently, there was inflated prices in the Aso ofiproducts at this point in time and other reverberating socioeconomic effects like 1916 Iseyin-Okeho riots.

In essence, British attacked local industries through legislations, banning the production of certain goods by the local craftsmen. It later discouraged the production of Aso ofi as well as usage of the cloth.

The study aimed to examine the origin of textiles production (Aso-oke) in Iseyin and the colonial impact on Aso Oke, identifying the factors influencing the production and usage in Iseyin and Yorubaland. It is obvious that much have not been written about the colonial policies and its impact onAso-Oke, its production and usage. This work will examine the colonial impact, particularly the harmful consequences of colonial policies, on Aso Oke production and usage.

Questions like how Aso Oke developed in Iseyin, its production process, types and sourcing for materials-locally or imported, factors influencing the production of Aso Oke will be discussed. In addition, the impact of colonial economic policies on Aso Oke production, the outcome of these policies on Iseyin and its environs, and the measures put in place in revamping the lost glory of Aso Oke in postcolonial period will be explicitly explained.

Iseyin the study area is one of the notable town in Oyo state and sixth largest town in the state. It is located and accessible through road networks from Ibadan, Oyo Abeokuta Saki and Ogbomoso. It has a total landmass of 1,419km and approximately 100km from the south of Ibadan. It currently has a total population of more than 359, 100.9 The period covers 1900 till date as the study covers the background history of cloth (Aso Oke) production, course of indigenous knowledge, colonial impact and what it is in recent times.

The research adopts a historical narrative and interpretation both primary and secondary data (including interviews, newspapers and archival materials, books journals and other internet materials.

The Iseyin Production of Hand-Woven Textiles (Aso Oke) in Historical Perspective

From time immemorial, it was said that the production of the traditional cloth requires relatively more complex processes such as the preparation of yarn from cotton plant materials, the dyeing of the yarn into required colourful thread, the acquisition of highly-technical skills for cloths weaving and the fabrication of tools and equipment such as looms, motor, spreaders, rollers and peddlers used by the entrepreneurs to produce the cloth. This, therefore, implies that a lot of entrepreneurial spirit, skills and culture are needed to carry out the activities involved in the weaving process so as to have positive result of the production.10

The promotion of the Aso-Oke ofi at this point goes through a very vigorous process, in an interview conducts on the 29th June, 2022 with Alhaji (Chief) Muraina Alarape Kangunhan (Aare Egbe Alaso/President of cloth weavers in Iseyin) he said the cloth production started from Iseyin community and that all the materials that are been used for cloth production are gotten from their farm.11

The production of the hand-woven textile in Iseyin have been said to have taken place one step after the other. Aso oke was handcraft which was passed down through the family linage and so almost all families in Iseyin are involved in the production of Aso-Oke even to the youngest of the family.

Iseyin cloth production can be classified into pre-weaving process and the weaving process. According to Alhaji Muraina Alarape Kangunhan the process of the production of Aso Oke by the Iseyin people basically include the following: planting and harvesting of cotton, seed separation of the seed from cotton, extraction of the thread from the cotton wool, stretching of the thread, dyeing of the thread and finally weaving.12

In Iseyin town the women were also the ones responsible for the extraction of thread from the cotton this process of extraction is called “riran Owu” with the use of molded machine made of clay and “Oparun” (bamboo) tree. To remove the seeds, ginning usually involves placing cotton balls on a block of wood and rolling an iron rod over them. The pressure exerted on the turning cylindrical object pushes out the seeds of the cotton fibres. After the seeds are removed, the fibres must be aligned and this process is called ginning. The ginning process which was confirmed to be done indigenously through a bow type device called Okure. This process produces the fluffy product which is ready to be spun into thread. Between five and six of the thread are said to be extracted at a stretch and folded into 60 roll.13

After all the thread have been extracted from the cotton, it is said that the women will prepare pots of dye and pour the extracted thread into the dye to bring out different colour. After ginning the process of spinning takes place in a traditional cumbersomely-manual way. The spinner pulls and twists enough fibres to secure it to a spindle. Though it was gathered that spinning sets can take two major forms, but in the case the spindle is weighted by a clay whorl. The spinner sets the spindle in motion draws fibres into a thread and winds them on the spindle. This instrument is called akowu. The extracted threads are them dyed into different colours, in which these dyes colour are responsible for the naming of any aso ofi produced at this time for instance the magenta colour dye used was what gave birth to the name alaari and for sanyan is the champagne colour dye and the sample are said to never go old in years.

There are three major types of Aso-Oke: etu, alaari and Sanyan with many variations, have been identified.14 However, modern names have been given to the designs such as baby computer, carpet, wire-to-wire among others. While etu is dark blue, sanyan has carton brown colour while alaari is crimson.

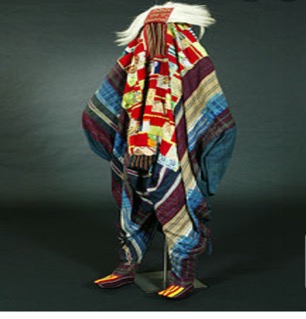

In Yoruba society, the Aso-ofi/Aso oke performed socio-cultural cum religious, gender and political functions. It is always socio-culturally reserved for special occasions where it is worn in a show of societal class, means of expression of communal, loyalty, solidarity and love and used in ceremonies like Yoruba traditional wedding (a compulsory groom’s gift item for the bride), burial ceremony, and for traditional religious purposes (like the Oro and other festivals where it is used to decorate religious objects). A testament to its religious usage is the hand-woven Egungun (Masquerade) costume made out of Aso Ofi as seen below:

Aso Oke is also gender indicative considering its differing usage among Yoruba men and women. Yoruba women use Aso Oke as girdle (oja) to stray babies, Ipele used as a covering cloth because of its thickness, buba (blouse), Iro (wrapper), gele (b) head-tie), Osuka (head pad for head-porters) and Iborun (shawl), which is usually hung on the should of the user were commonly worn by the Iseyin and generally the Yoruba women of precolonial, colonial and postcolonial Iseyin. Depending on the functions and textures, these clothes were classified into casual cloth (aso iwole/Iyile) traditional hand-woven textile for everyday use and traditional hand spun thread or with industrial threads to produce lighter cloth as domestic and social function clothes known as kijipa or ikale, otigba meta and ala which are sown up buba (blouse) and iro (wrapper).15 The Yoruba men also cloth themselves in aso-oke for work and other social ceremonies. For the Yoruba men, the aso-ofi in the ancient times was worn as work dress on their farms, and sow it with full agbada for ceremonial occasion, agbada siki, sokoto kembe mostly used by the chiefs, abeti-aja for cap and they also use it for social, religious and traditional ceremonies. They wear a complete dress consisting of Sokoto(trousers, buba (top) agbada (large embroiled flaming gown) and abeti aja (cap).

In Iseyin where men’s weaving is very prominent, a small percentage of the women also weave and though some of the cloth produced are used to mark important events in the life of the women (including marriages, birth of babies and other social functions), most of their cloths serve domestic purposes in the form of blankets, towels, and work clothes.16

Aso-oke was often used as symbols of political prestige. According to Pa Dauda Olajori:“In the history of the old Oyo Empire, Iseyin was part of the area under the old Oyo empire, and part of the tribute which the Alaafin collected from Iseyin was their hand-woven cloth which was said to be rated high in terms of tribute paid to Alaafin”.17 Also is in the case of Christian missionary who received the gift of Aro-oke from Alaafin Abiodun in old Oyo empire.18

Factors Influencing Weaving

Generally, weaving is sometimes influenced by the availability of capital, low patronage and the cost of maintaining the loom. Others include low profit, weather condition, the influx of Western garment and occasion people want to do. Availability of capital to purchase raw materials in bulk often affects the weavers. When the level of patronage is low there will be less motivation to produce in large quantities. Besides, weaving on a loom is equally demanding as it involve exertion of strength and energy among the weavers. Today, wearers are using more colour fast yarns to produce a more durable fabric. Light might and shrink resistance could enhance a better product.19

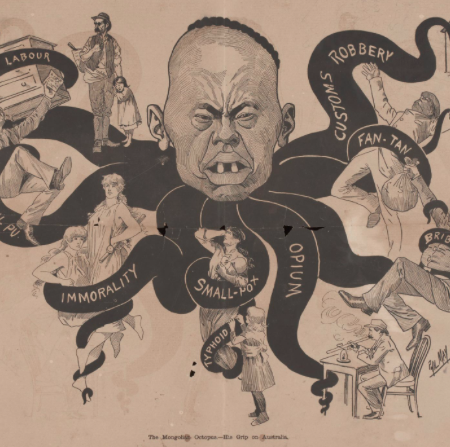

The Colonial Impact on the Aso-Oke Production and Usage

The British policy in Nigeria from 1886 has been said to be designed to knock down the home industries in other to guarantee continuing importation of British made goods to her colonies which Sir Lord Lugard implemented. With Lugard’s policy of indirect rule (the use of traditional rulers and chief as intermediary to help implementing British government policies in Yorubaland) which was predominant in Yorubaland the colonialist was able to gain direct access to the land, human and farm produce of the Yoruba people. During the colonial era, cotton was widely cultivated as an export commodity. Now varieties of cotton introduced during this fine may have been responsible for its large-scale production relative to the pre-colonial period. Cotton cultivation was promoted in the British reigns of Yorubaland by the British cotton growing Assocation (BCGA), formed in 1901.20

The policy of commercial forming introduced greatly affected cotton farming Iseyin. This gave impetus for the production of cotton exportation to foreign market rather than using it locally. So the thread became scarce. This limiting the production of Aso-Oke in Iseyin. There was also the huge imposition of tax on cotton planters and textile weavers, which made the farmers and the weavers to work harder and earned little as profit because the profits have gone to the taxes paid to the colonialists through the middle-men. In corollary to this policy of indirect rule, there was a report of riot in 1916 which took place in Iseyin/Okeho axis at this point and was said to have happened in Ode-Oba. There was a fight against the British representative on huge levies of taxes which was placed on the cotton produces and cloth weavers in Iseyin. While reacting to this, Alhaji (Chief) Muraina Alarape said, the riot was a self-caused riot because the intention of the colonialist was to attack the Okeho, but the Iseyin people barri-coded the road with timber and rocks for two days and cutting off the Odo-ogun bridge fighting branchy in solidarity with Okeho but were overpowered by the superiority of the colomalists.21

As a result of these colonial polices in Yorubaland, handcrafted textiles with smuggling activities along Nigerian coastal towns and land boarders became a major obstacle to the growth of the textile industries. In essence the British colonialists attacked local industries through legislations banning the production of certain goods by the craftsmen. Other crafts were systematically taxed to raise their general cost of production, making them uncompetitive against foreign goods.

On a final note, the implication of these policies discouraged the production of Aso-Oke as well as its usage. The cotton produced were no longer meant to serve local hand-woven textile industry rather to serve the European industry to produce the western clothes.

Western Influence on the Production of Aso-Oke

After colonialism, much more developments have been discovered to have taken place in the production of Aso-Oke in Iseyin which has led to changes. The changes start with the production process of Aso-Oke, there emerged the large importation of different kinds of threats, rather than the usual manual production of thread.

No one is interested in the cultivation of cotton and manual extraction of thread which were said to be long lasting compared to the imported ones. In fact there was a notion of lazy attitude which has taken over the textile production and business. According to Alhaji (Chief) Muraina Alarape “the youth are no longer interested in working hard to sustain legacies of the forefathers in the Aso-Oke business and more so putting on Aso Oke today depicting that you having an occasion”22.

In the contemporary time, due to the Western influence of the importation of all kinds of production material particularly thread have expanded on the use of the Aso-Oke, a single panel of cloth may even be worked into a wooden chain to serve as the backrest as well as the seat, curtain, bed sheet, bags, shoes and other commonly used materials.23

Also the new textiles being cut and sown into different style, some even go to the extent of merging the Aso-Oke with other textile materials such as lace and Ankara. The western styles have also taken charge of local textile industry.

Revamping the lost Glory of Handwoven (Aso-Oke)

With the attainment of Independence, there was the re-emancipation of the traditional clothes in Nigeria, thereby people had to go back to their wardrobes and bring out their originality made clothes including the Aso-Oke just to express themselves and portray freedom from the hand of the colonialist, this therefore again popularized the traditional clothing tradition and later at the turn of the 20thcentury aso-oke became tied to Yoruba (and Nigerian) cultural identity. Yoruba intellectuals (often from slave returnee families) rejected the formal wear of the British Empire in favour of this local cloth. The twentieth century witnessed an increasing surge in demand for Aso-ofi which has meant that its production is widespread throughout southwestern Nigeria. it has become synonymous with Yoruba identity and the cloth is used for the manufacture of garments associated with prestigious moments such as weddings, graduations, religions festivals (of all beliefs) and other important events.24

In a bid to promote the production, marketing and usage of Aso Oke, on the 16th September 2017. Aso-Oke international market was established in Iseyin. The market since establishment has promoted and still promoting production, sales and usage of Aso-Oke in contemporary times.25

Also, the programme tagged “Aso-ofi day” is also a way of revamping the lost glory of Aso-Oke, it is a way of celebrating tradition, culture, tourism as well as economic opportunities of the Iseyin people and also interested by dignitaries from different walks of life.

Conclusion

This research has documented the history of weaving activities, process of production, usage and the colonial impact. It revealed that colonial impact affected the production and sometimes availability of capital and cost of maintaining the 100m. Though up till recent times, these has been increase in the purchase and patronage or Aso-Oke in Iseyin which has also helped in sustaining the production of hand-woven textiles in the area; that is why when you get to Iseyin today, most of the family are still very much involved in the business, in fact there is no other vocation in Iseyin than the production of Aso-oke. This goes with the popular saying that “show me a place in Iseyin without where they are doing Aso-ofi and I should you bank without money” which means all the compound in Iseyin are Aso-ofi producers.26 This is relatively true in the sense that Aso-ofi production is the major vocation of these people and almost all the compound are endowed with this indigenous knowledge.

Despite the fact that the Iseyin people are still preponderantly involved in the hand-woven textile business there has been much wind of change over the years in the production process, these which ranges from procurement of equipments and use of foreign thread which gave way for mass production of the Aso-ofi compared to the past. The obnoxious attitude toward the production and involvement of the youth should be adequately revived by supporting them and promoting the production and usage of Aso-Oke/Aso ofi.

END-NOTES

1‘Wole Adeniran. (2010). Economic History of Nigeria up to 1800 for Undergraduates. Oyo: Adexsea Publisher.

2Fakunle, O.A. (2022). Historicizing Dress (As[–)f8) production in Iseyin Town, Southwestern Nigeria https://www.research gate. Net 1358752114.

3Diyaolu, I.J. & Omotosho, H.R. (2010), “Role of dress in socio-cultural events among the Ijebu-Yoruba, Ogun State, Nigeria: Journal of Home Economics Research 13,35-41.

4Ademulaya, B.A. (2014). “Ondo in History of Aso-Okewearing in Southwestern Nigeria Mediterranean Journal of Black and African arts and civilization 5(II) 129-114.

5Interview conducted with Mr. Kaolawole Akeem on Aso-ofi weaver and seller in Iseyin Town-Age 41 29/06/2022.

6Olutayo, A.O. & O. Akinle (2009). “Aso-Oke (Yoruba hand-woven textiles) usage among the Youths in Lagos Southwestern Nigeria: International Journal of Sociology and Anthropology. 1(3) 62-69.

7Ibid (2009).

8Asakitipi, A.O. (2007) “Function of Hand-woven Textiles among Yoruba men in Southwestern Nigeria. Nordic Journal of African studies 16(1) 101-115.

9www.citypopulation.php>iseyin.

10Interview conducted with Alhaji (Chief) Muraina Alarape Kangunhan (Aare Alaso oke/President of Cloth weavers Association in Iseyin, Age 91 on 29/06/2022.

11Interview conducted with Alhaji (Chief) Muraina Alarape Kangunhan (Aare Alaso oke/President of Cloth weavers Association in Iseyin, Age 91 on 29/06/2022.

12Interview conducted with Alhaji (Chief) Muraina Alarape Kangunhan (Aare Alaso oke/President of Cloth weavers Association in Iseyin, Age 91 on 29/06/2022.

13Interview conducted with Mr. Kolawole Akeem an Aso ofi weaver in Iseyin Town Age 41, on 29thJune, 2022.

14Aremu, P.S.O. (1982). “Yoruba Traditional Weaving: Kijipa Motifs, colour symbols “Nigeria Magazine, No. 4.

15Rea, W. (2013). Yoruba Textiles, cloth and tradition in West Africa. University of leads International Textiles Archive. http://www.adireafricantextiles.com.

16Interview conducted with Pa Dauda Alajori an Aso ofi weaver in Iseyin Town Age 62, on 29th June, 2022.

17Interview conducted with Pa Dauda Alajori an Aso ofi weaver in Iseyin Town Age 62, on 29th June, 2022.

18Interview conducted with Alhaji (Chief) Muraina Alarape Kaghnahan (Aare Alaso oke/President cloth wearers Association Iseyin Age 91 29th June, 2022.

19Interview conducted with Pa Muka Afonfere as aso oke wearer in Iseyin Town. Age 60 29th June, 2022.

20Asakitipi A.O. (2007). Functions of Hand-woven Textiles among Yoruba women in South western Nigeria Nordic Journal of African Studies 16(1) 101-115.

21Interview conducted with Alhaji (Chief) Muraina Alarape Kangunhan (Aare Alaso oke/President Weavers Assocaition? Iseyin Age 91 29th June, 2022.

22Interview conducted with Alhaji (Chief) Muraina Alarape Kangunhan (Aare Alaso oke/President Weavers Assocaition? Iseyin Age 91 29th June, 2022.

23Interview with Mr. Kolawole Akeem an Aso ofi weaver in Iseyin Town Age 41, on 29th June, 2022.

24Atanda F.A. (2015). An Evaluation of the Indigenous Textile (Aso-Oke) Industry Performance in Yoruland Southwestern Nigeria. foundation Journal of Management and social sciences: 4(1), 114-131.

25Interview conducted with Alhaji (Chief) Muraina Alarape Kangunhan (Aare Alaso oke/President of Cloth weavers Association in Iseyin, Age 91 on 29/06/2022.

26Interview conducted with Alhaji (Chief) Muraina Alarape Kangunhan (Aare Alaso oke/President of Cloth weavers Association in Iseyin, Age 91 on 29/06/2022.

Good morning publisher,

I do not know if I can get a direct contact of the above article author.

Thanks and warm regards.