Introduction

On the morning of February 1, 2021, Burma woke up to its incomplete past. Encountering the fourth military dictatorship, re-emerging from its political hideout, changed the atmosphere of the country into chaos, altogether with the effects of the pandemic. The longevity of authoritarian rule patterns has inflicted fractures and inequalities in the social fabric of society. Burma is almost a time capsule with just a dash of globalization in its veins. Land of golden pagodas as well as wars. It was only within the past decade that its development shows a slow shift towards democratization. Burma has lived through different forms of governance: the pre-colonial era of various dynasties, the British colonial rule, the four years of Japanese rule (1942-1945), post-independence parliamentary rule, and the military government, succeeded by a then-quasi-civilian government. The result is the phenomenological experience of Burma, from the inside, which is a mixture of several historical remnants: colonial legal system, conservative Buddhism, and superstition influenced political views and moral systems, which entrench from the time of the kingdoms. The long-term sequelae of these historical, socio-political affairs and conflicts are deeply rooted within the daily lives of people living inside Burma.

A day in Burma can be influenced by almost everything. Its social education system has failed to protect people from all sorts of basic epistemic illogical news and rumors. Social Media hatred and false information spread have no safeguard, and push of rights by activists have drowned to death in the sea of misinformation in the most needed times. The concept of rights and the contemporary understanding of democracy in Burma, as a concept, is also not widely developed. The liberal tradition of rights-based democracy is credited to Aung San Su Kyi by scholars. In the west, she is seen as a bringer of change to Burma, both a Nobel laureate and an effective liberal leader. But in reality, it is a different matter. When she says to the people,“ We have the right to something,” people absorb and amalgamate that into their Buddhism-influenced discourse. People, thereby, think of rights in the duality, and these dual-viewed rights are embodied in the figure of Daw Aung San Suu Kyi, as Burmese people see her sacrifice together with that of Siddhartha prince (Than Myint-U) and anything she did become forgivable and tautological, Aung San Su Kyi became people’s reference for rights. As U Kyi Maung, one of the founders of the National League of Democracy party stated in the interview with Dominic Faulder:

Her political goals became the shared political goals of her supporters, the majority of people. Aung San Su Kyi and her fellow civil politicians from 2010 and onward faced challenges, encountered crimes against humanities but they had failed to overcome and speak out the matters, rather they compromised, and the public in those years seemed to agree with their politicians too. Those years saw the rise of Bamar-centric nationalism centering around the National League of Democracy party’s political charisma, with civil politicians and the military on one side and the other ethnic groups on the other side. There were removals of ethnic leaders’ statues, declaration of the Arakan Army(AA), an ethnic armed organsation led by General Htun Myat Naing, as a terrorist group, and the active negligence of majority people upon civil wars causing great harm to properties of ethnic minorities all across the nation. In an 2019 interview with the Irrawadddy news, AA Chief General Htun Myat Naing anticipated the current political turmoil and warned the central government:

We start with a short study on citizenship in Burma, followed up by a report on discrimination against religious and ethnic minorities. Next in order is a case study on how suppression and marginalization of Arakanese people gave rise to their own quest for freedom, and we finally finish up with the enrolling narratives of contemporary Burma.

Citizenship Laws in Burma and Systemic Discrimination against minorities

Public reflection of citizenship in Modern Burma does not strictly follow the conception of a citizen as a political agent or a person with legal status and protection, obtained either from recognizing the birth or participation of that person by the state. Rather, it serves as a tribalistic identity, shaped by nationalism, religion, and military incentives, that you navigate through the state apparatus of inclusion hierarchy. In pre-colonial times, if a person presents himself or herself as loyal to the king, he or she becomes a subject of that king and others will view the concerned person as a subject of the sovereign power, still, the subject’s identity holds a foreignness but not a foreign threat. Even when foreigners in Burma’s history decided to take an offense against then-existing kingdoms, they were seen as a threat only to sovereign power and were battled against accordingly (see Filipe de Brito e Nicole). The anti-immigrant sentiment dates back to the colonial period. The economic recession in the late 1930s and the rise of nationalist independence movements coincided. Burmese politicians at the time viewed migrants as a factor in exploiting Burma’s land and labor (Walton, 2013).

The earliest laws regarding citizenship first appeared under British partial rule in 1864, before the third Anglo-Burmese war. This was the first legal development of categorizing foreigners and non-foreigners in the Burma context. The 1864 Foreigners Act, India Act III enforced the prevention of ‘Foreign subjects’ from residing in Burma without consent. The first passport act which is still in effect with minor amendments and the first use of certification to identify foreign residents were implemented by the British in 1920 and 1940 respectively (José María Arraiza and Olivier Vonk, 2017). The 1947 Constitution of the Union of Burma, ratified right after independence, defined being a citizen as uniform throughout the union. It adopted the concept of being indigenous and foreign from the colonial era, that is to imagine the primary citizens of Burma as the ones living in the country before the colonial invasion. The result is that the eight main ethnic groups: Kachin, Kayah, Karen, Chin, Burmese, Mon, Arakanese, and Shan became the references for being native citizens. Besides these criteria, any person descended from ancestors who have lived for two generations and any person whose parents and himself were born in Burma were qualified to be a citizen, as defined in the Union Citizenship Act of 1948. Although the constitution required citizens to apply for certificates, it was not mandatory, only foreigners are required to register through the 1940 foreigner registration act. This was how a legal framework between an indigenous citizen and a foreigner started to take shape.

In 1962, the military took over the government and formed a ‘Revolutionary Council’ led by General Ne Win. And, in 1974, the Council ratified a new constitution. This new Constitution of 1974 alternated the being citizen as “born of parents both of whom are nationals of the Socialist Republic of the Union of Burma” (Constitution of the Socialist Republic of the Union of Burma). However, it did not yet repeal the 1948 Citizenship Law.

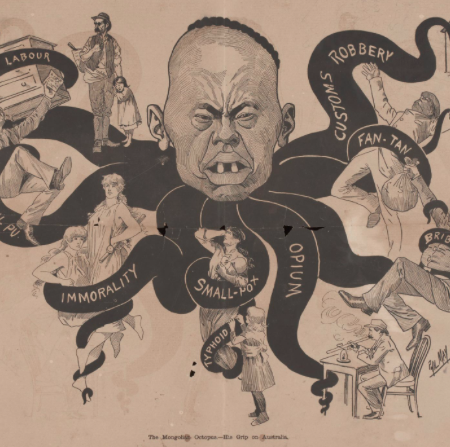

During the time of drafting the constitution, Bangladesh was going through a war of liberation. The end of the war with the triumph of Indian–Bangladeshi forces, worried the military government for the borderland crisis between dividing lines of two nations which had not solidified yet, and there was a certain chance that the military regime might view the refugee crisis as a foreign invasion threat. The military council increasingly issued foreign identification cards and enforced them. In the year 1978, the government initiated “Operation Dragon King” (Nagamin), which purpose was to identify people in Arakan, Chin, Kachin, Mandalay, and Sagaing as either citizens or foreigners. Accelerating of discrimination meant a need for a profound legal foundation which was facilitated by the citizenship law of 1982. This 1982 citizenship law introduced the three tiers of citizenship, each with varying degrees of rights. It inherited the idea of full citizenship belonging to the eight main ethnic groups from previous laws. Citizens become members of the eight national ethnic groups. Associate and Naturalized citizens were subjected to give “conclusive evidence” to be certified in their respective citizenship, and that mentioned citizenship could be stripped away without any reason. The controversial 1983 nationwide census immediately followed the limitations of the newly enforced law. Notably, the Arakan state census report categorized people not belonging to the indigenous races as “Bangladeshi” (1983 Census), and the Government refused to issue them a proper certification. The regime also introduced the controversial 135 national races categories.

The creation of 135 nation races itself has embedded characteristics of coloniality. Colonial administrations used ethnic compartmentalization as a technique of rule across Southeast Asia, the view of Europeans on orient identities affected the colonial practice, and ethnic fences were constructed, an example would be the ethically compartmentalized Malaya 1921 census. (Stockwell, A. J. 1998) These colonial methodologies were accepted even by the nationalists and institutionally persisted throughout post-colonial Burma as the state’s governing tools. The exact genesis of 135 national races is still ambiguous. One explanation is that the national races are a continuation and adaptation of the 1931 British census which listed 135 spoken languages in Burma (Ferguson 2015). However, the earlier lists of national races by the Burma Socialist Programme Party, before the 1973 census, did include Burmese Indians, and Burmese Muslims.

The discriminative nature of institutionalized 135 national races excluded many groups: Panthays Chinese Muslims, Burmese Indians, and Rohingyas, and the categorization of “national race” has become the gold standard to enjoy citizenship rights and other rights in Burma. The current 2008 constitution maintained the discriminatory status. Burma citizenship laws are exceptionally problematic for people who do not have historical documentation to be eligible for full citizenship. Consequently, marginalized groups become stateless and are forced to obtain a foreigner status, thereby omitting the chances of new generations of marginalized people from becoming nationals of Burma, violating the children’s rights granted in article 7 of the ‘Convention on the Rights of the Child’ that every child must acquire a nationality right after birth.

The most internationally renowned case of human rights abuse from Burma is that of Rohingya people. Rohingya people are ethnic Muslim minorities who practice a Sufi-inflected variation of Sunni Islam. Explaining the origin of Rohingya Muslims is quite a thorny case. There are two questions presented in search of Rohingyas origin. One is how long Muslims in Arakan have resided in the region. And the other is that of the equivalence between early Muslims to the present-day Rohingyas (Nemoto, Kei 1991). According to the third-party perception of Moshe Yegar, an Israeli national, the first Muslims settled in Arakan from 1526 to1857. They were mostly from Bengal. He viewed this first migration as an origin of the Rohingya people. Another two waves of immigrants arrived during the nineteenth and twentieth centuries when Arakan was governed by colonial rule as part of British India, and those migrants assimilated into pre-existing Rohingya communities. (Nemoto 1991).

Between 1952 and 1956 minorities seeking citizenship can be registered through the Burma registration act (Arraiza and Vonk,2017) and Rohingya people who met the criteria got the National Registration Cards (NRCs) along with other ethnic groups since the law in effect at that time provided citizenship to “every person born in any of such territories. Britannic Majesty’s dominions” (Constitution of 1947). The problem of denying minorities’ citizenship accelerated after General Ne Win’s government took power in a 1962 coup d’etat. Established regions such as the Mayu frontier district which was a major Arakanese Muslim region, created under the first prime minister U Nu government, were dissolved back into Arakan after a direct rule by the military (Nemoto 1991). In the 1970s, with the concern of illegal immigration from Bangladesh, the military government issued Foreign Registration Cards in the area and forcefully labeled Rohingyas as Bengalis. Operation Dragon King (Nagamin) and Operation Clean and Beautiful Nation (Pyi Thaya) in the years 1978 and 1991 also forced out Rohingyas to Bangladesh. The modern-day displacements began in 2012 when violent affairs broke out between Buddhists and Muslims in Arakan, and State-backed armed forces targeted Rohingyas and Muslim townships in Arakan, essentially displacing 200,000 Rohingyas. Following up this series of events was the 2014 census which excluded Rohingya people from citizenship with its discriminatory 135 national races categorization. The military again struck the Rohingya communities after the attack on Burmese police officers by the Rohingya militants in 2016, from this point on, the genocide continues even under the quasi-civilian government in the name of reconciliation, and Rohingya were labeled as illegal immigrants from Bangladesh, despite their ancestral roots, and generations of residence. Before 1962, some Rohingya even got high positions in politics and got rewards too. Rohingya gentlemen had been appointed to be the Honorary Magistrates of the third class in the Akyab District by the U Nu Government in February 1947.

We interviewed the grand-grand daughter of one of the Honorary Magistrate. Interviews with her are conducted via the internet in 2021 November, for the sake of interviewee security she will be described as Hsu. Hsu is a 22-year-old Rohingya girl, living in Sittwe Camp, Arakan. With a feeling of betrayal, she described the events, which she had gone through, vividly:

Indeed, Rohingyas are not welcome in secondary schools and high schools in Arakan. One of the main obstacles is the lack of proper certification. If both of the minority parents do not have citizenship certification cards, the child cannot have access to higher education or jobs and many parents withdraw their children from schools due to this lack of promising future. The treatment in the schools also affects the minority Islamic students. There have been overwhelming Islamophobic discourses in the region, plus school systems and lessons in Burma are very Bamar-centric. Libelous terms are used against minorities such as ‘Kalar’ by peers and teachers.

Hsu was one of the victims who lost her chance to pursue higher education due to her identity as a Rohingya. The Ministry of Education did not grant her permission to study at Yangon University, despite her academic performance. They only allowed her to submit to Sittwe University in Arakan State; this university did not also accept her. She melancholically recounted:

Chaos in Civil Society: Precursors to the Present Situation

Religious freedom and the right to publicly profess Islam and other religion such as Christianity have been colliding with the Bamar-Buddist majority State. Religious conflicts are intrinsically linked to the Christian identity of ethnic peoples with an assumption that the Burmese Christians are not loyal to Burma culture and that Christianity is a religion designated for the Western population. During the colonial period, people viewed the Burmese Christians as the same as the British, subsequently ensuing the exodus of foreign missionaries from Burma.

The Burmese military government always presents itself from state-controlled press media to disseminate the idea of Buddhism and use it to bolster their legitimacy. Through this media, they showed them making donations to pagodas, monasteries, and Buddhist temples, All these activities by the Burmese military were meant to seek some semblance of the legitimacy of themselves through Buddhism by the unspoken ideological statement that they are the only one trying to keep Theravada Buddhism in practice.

In the case of Islam, Muslims have participated in the political and social positions of Burma since the British colonial days and the early years of independence. They included U Razak, who is one of the 9 martyrs of Burma, and U Raschid, who was the first general secretary of the Rangoon University Students’ Union. Minorities formed an indispensable part of governmental positions and civil society.

Modern religious frictions and conflicts between Muslims and Buddhists first erupted in 1997 which is now known as the 1997 Mandalay riots, which followed after reports of Muslim men allegedly attempting rape against a Burmese girl. Over a thousand Buddhist monks and other people burningly spearheaded anti-Muslim demonstrations, including the acts of destroying Muslim mosques, vandalization of houses, shops, and vehicles, looting and burning of religious books and sacred relics. In 2001, religious riots also broke out in Taungoo, in the Bago division, resulting in the deaths of around 200 Muslims, the demolition of 11 mosques, and the burning of over 400 houses. About 20 Muslims who were praying in a mosque were killed and some of them were beaten to death by the junta forces and the mosques in Taungoo were shut down (CNN 2012).

This marked the commencement of numerous riots erupting all over central and eastern Burma, mostly led by Buddhist monks who declared to go on a crusade of Buddhist nationalist movement against Islam. The propagation of this militant Buddhism was highest between 2010 and 2018. The Patriotic Association Of Myanmar (Ma Ba Tha), a nationalist Buddhist organisation, was formed in 2014, which lobbied for protection of race and religion bills. There were summer youth Buddhist camps everywhere, teaching how to protect Buddhism from external threats. Those camps taught the young that Burma is their land, soil and Buddhism is their religion and if someone disturbs this status quo they must restore it even if what it takes is “fencing the borders with their bones.” The most recognizable figure among the radical monks would be Wirathu and indeed, the figurative place of religious officials play a huge role in stirring up anti-Muslim sentiment and conflicts.

The Bamar-centric education system also adds up to systemic discrimination. A typical morning of a student goes like this, he or she wakes up, goes to school. At the school, there awaits a national flag. When the time arrives, the national anthem rings from the school intercom system and every student has to give a salute and remain still for the time being. In the classroom, before the lessons start, regardless of their religion, students have to pay homage to Buddha. Dress codes other than “Bamar-like” are not allowed. All anti-Muslims personals give the same and repeating nauseous answers that the minorities will engulf and take over Buddhism.

The so-called “Burmanization” or “Religious Nationalism” ensued devastating persecution not only towards Burmese Muslims but also towards Burmese Christianity, too. There were widespread proselytization campaigns against the Christians by the Burmese military since the 1990s, restrictions on churches, and freedom to profess Christianity, forced labor conscription, physical violence as well as massive displacement of Burmese Christians, especially in Kachin and Chin states of Burma (Harvard Divinity School, n.d., UCA News, 2021).

Suppression, Marginalization and Quest for Self-Determination in Arakan

The impacts of Burmanization can be well witnessed in the case of Arakan State, Arakanese Buddhists and Rohingya Muslims. The crisis in Arakan State is multifaceted with nationalism, religion, financial and resource allocation, history, and socio-economic conditions being inexorably linked to each other. Among different nationalities fighting for self-determination in Burma, the context of Arakan is different in terms of political aspiration and the meaning of self-determination. The widely held notion of self-determination for all ethnic nationalities in Burma through the framework of federal democracy by many ethnic armed organizations is perceived to be incomplete by Rakhine political forces. Self-determination of Arakan under the framework of confederation has become one of the principal goals of Rakhine political forces, such as the Arakan Army (AA) (Pwint N. L., 2019).

Hence, it is worth exploring what drove the Arakanese people to consider confederation instead of federation as the only means to sustain peace in Arakan State, how the actions of the civilian government of Burma under the influence of the military made political means completely off the table, and what the future of Burma lies ahead. Herein, the questions arise as to whether the Arakanese are truly able to exert their right to have a say and make a difference in Arakan State, and Burma to a wider extent. This entails how the widely acclaimed Burma democratic transition of 2011-early 2021 revealed wider disparity between Bamar and other ethnic nationalities.

Historical grievances of Rakhine Buddhists have given rise to militaristic forms of nationalism. Bitterness started when Burmese King Bodawpaya of Konbaung Dynasty conquered the Kingdom of Mrauk U (the modern-day Rakhine State) in 1785, and the revered, Mahamuni Buddha image was transported to Mandalay in Bamar heartland. The Rakhine were only granted to have ‘Division’ instead of ‘State’ after independence due to a lack of collective front within Rakhine Buddhists and Rohingya Muslims, and the political maneuverings of Bamar leaders (Yunus, 1994). Myanmar’s 1974 constitution under the military dictator Ne Win constituted the “Rakhine” State from Arakan Division (Yunus, 1994). On the eve of Myanmar’s incomprehensive democratic transition in 2010, Rakhine was the second poorest state in Myanmar after Chin State despite possessing substantial natural gas reserves (Integrated Household Living Conditions Survey in Myanmar, 2009-2010).

Apart from socio-economic destitution, Naypyitaw failed to reconcile with the Arakan populace through political means under both the Union Solidarity and Development Party (USDP) and National League for Democracy (NLD) governments. Political transition and the resulting relaxation of freedom of expression, did not result in greater autonomy and self-determination of Arakan people. For instance, the chief ministers of Arakan State between 2011 and the beginning of 2021 were members of the then-ruling USDP and NLD parties, despite both parties winning seats second to an ethnic the Arakan National Party (ANP) in 2010 and 2015 general elections (Kyaw, 2016). People of Arakan had hoped the NLD, headed by a Nobel Laureate Aung San Suu Kyi, would recognize their political rights, so, the NLD’s appointment of the Arakan State cabinet with its own party members especially without the consultation with Arakan political forces failed to reconcile the central government and Arakan people. The Arakan people’s loss of faith in central civilian government and electoral democracy did not end there,

In January 2018, 7 people died and many people injured after police had opened fire on the audience commemorating the fall of Mrauk U Kingdom (Myint, 2018). Dr. Aye Maung, a prominent Arakan politician from the ANP, was also charged with high treason for speaking out about systematic suppression of Bamar political elites on the Arakan, and suggesting that military means could be the only way to achieve Arakan’s self-determination (Lynn, 2018). In fact, the option of armed struggle had already been on the table with a Arakan ethnic armed organization, the Arakan Army (AA) having trained and moved troops along the Arakan-Chin state border since early 2015.

Since its attack on police posts on Burma Independence Day in 2019 , the AA and Burma military had been embroiled in frequent, intense clashes and skirmishes including the military’s use of air strikes and artillery under so-called clearance operations, killing and injuring many civilians. The AA and its relatively young leadership want the status of Arakan State to not be lower than that of confederation, being enjoyed by the United Wa State Army (UWSA) in the Wa Self-Administered Division, which has long had close ties with China (Pwint N. L., 2019). Unlike other ethnic armed organizations (EAOs) in burma, the AA has mainly used asymmetric warfare, and social media to spread its revolutionary ideology of #ArakanDream2020 and “the way of Rakhita”, via social media platforms particularly via Twitter.

With the growing popularity of the AA due to its tactics, the prospects for political settlement became gloomy with subsequent actions of the-then civilian government, which held the belief that uncompromising military response is the key to ending the crisis. The NLD government and President Win Myint designated the AA as a terrorist group under the 2014 Counter-terrorism Law and the 1908 Unlawful Associations Act (Nyein, 2020). In addition, the two biggest Arakan media, Narinjara and Development Media Group were designated as fake news outlets, and the government instructed telecom services to block their contents in fear of the spread of news outlets’ reports of government’s brutal response to Arakan people and human rights violations conducted by the military (Human Rights Watch, 2020). In line with the uncompromising nature of the-then civilian government, the military excluded the AA from its unilateral ceasefire with ethnic armed organizations Furthermore, over 1.4 million people were affected by a prolonged internet ban which had been put in place by the government upon the military’s request since June 2019 (Hlaing, 2020). The internet ban has undoubtedly restricted dissemination of information about the COVID-19 pandemic. Several townships in Arakan were declared unsafe to hold 2020 general elections by the-then Union Election Commission with poor transparency and without proper consultations with the Arakan people and politicians (ReliefWeb, 2020).

The political landscape of Rakhine State has changed in an unprecedented and uncertain way following the military coup of 1 February 2021. In order to portray themselves a magnanimous political force to reconcile different ethnic nationalities and to deter another battleground amid popular protests and strikes, the junta removed the AA from a terrorist designation on 11 March 2021, and released a Rakhine nationalist politician Dr. Aye Maung on February 13 (Hlaing, The Diplomat, 2021). The Arakan National Party, which is the largest Rakhine party which won majority of votes in 2015 and 2020 general elections, accepted to take up a seat of the military’s State Administative Council (SAC), while the majority of ethnic parties rejected the SAC’s offer (Hlaing, The Diplomat, 2021). Furthermore, Dr. Aye Maung, who had been charged with high treason under the NLD government and released by the SAC, is showing signs of agreement with the SAC’s proposal to adopt a proportional representation (PR) electoral system (BBC Burmese, 2022). On the other hand, other prominent ethnic parties, such as the Shan Nationalities League for Democracy (SNLD) rejected the junta’s proposal, Stating that the adoption of PR is fruitless with the presence of the military in Myanmar political arena and the military orchestrated PR elections will only enhance the military’s grip on power (The Irrawaddy, 2021). These factors along with Arakanese political forces’ relatively late response to military’s brutal crackdowns were criticized by the Bamar public, which further deteriorated relations between two ethnic nationalities. However, it does not mean that Arakan State is peaceful and the AA is colluding with the military. In fact, the AA is accelerating the process of the “Way of Rakhita”, the move towards complete self-determination of Rakhine nationality step by step, while fighting alongside other EAO allies against the SAC in other parts of Myanmar (Hlaing, The Diplomat, 2021) (Lynn K. , 2021). It is worth noting that grievances and ethnocentric views are not the only motivators that have led to the birth of the AA and Rakhine nationalism. Contrary to what some media outlets and politicians predicted, the AA leadership has shown a tolerant and inclusive outlook on all ethnic nationalities with different faiths in Rakhine State. For instance, the AA promised to include Rohingyas in local administration (Hlaing, The Diplomat, 2021) Above all, the AA chief Twan Mrat Naing in his recent interview stated that the AA recognizes the human rights and citizenship rights of Rohingyas (Altaf Parvez, 2022).

The contemporary situation in Burma: Rights and Democracy

Since the recent overthrow of the government, unionists and activists’ voices are propagating and growing larger in public political discourse and they offer an alternative view to past political views, and it is through this activism that most of the people in Burma started major strikes and breakthroughs in the course of the current political timeline. The first major strike was that of the Civil Disobedience Movement (CDM) by hundreds of thousands of civil servants including students, bankers, medical workers, engineers, teachers who refused to go to work. The response of the 2020 election winning politicians, majority of whom are partisans of National League of Democracy party (NLD), was by creating a counter committee-Committee Representing Pyidaungsu Hluttaw (CRPH), grouped with ousted lawmakers of Burma’s Lower and Upper house. Massive protests broke out from the side of the Myanmar citizens demonstrating their dissent of the coup, starting from the sixth of February. As protests went on, the military banned gatherings in townships across ten regions as of February 9, and continued its use of lethal force against protesters. On 14 March 2021, 38 civilians were killed and countless more were injured by security forces. This marked the deadliest date since the coup on February 1st. By the end of March, 2729 people were in detention, 120 were issued warrants and 536 people were killed in brutal crackdowns (Assistance Association for Political Prisoners, 2021). On March 30, CRPH released the federal democracy charter. The charter outlined to form the interim National Unity Government (NUG). On April 16 CRPH announced the line up of National Unity Government, composed of 11 ministries and 26 members. On May 5, the National Unity Government (NUG) announced the creation of a “People’s Defense Force” (PDF) to oppose the military regime as a “forerunner of the federal armed forces”. PDFs were formed by NUG with Myanmar youths and pro-democracy activists in response to the violence happening throughout the country. Many PDFs are also trained by ethnic armed organizations (EAOs). On 28 May 2021, the NUG released a video of the PDF’s graduation ceremony, announcing that the armed wing was ready to challenge the military junta’s forces. Throughout the country, there are estimates of 193 PDF groups and another 12 independent armed groups in this political scene (Institute for Strategy and Policy Myanmar, 2021).

Starting from the day of the coup, the military formed the State Administration Council (SAC), which oversees all the governmental issues in Burma right now. The narrative carried by the junta is that 2020 general elections were unfair, and they are the one restoring Burma from authoritarian turmoil. On May 12, 2021, the newly formed Union Election Commission under the State Administration Council (SAC) met with a total of 59 political parties in Nay Pyi Taw to replace the existing first-past-the-post (FPTP) with proportional representation (PR) arguing that FPTP suffer minority ethnic groups and small political parties in terms of parliamentary representation and favor large political parties due to its inherently built-in, significant vote-seat anomaly. Based on the newspapers by Junta between January 1st and 8th, they are disseminating the narrative that SAC promotes the well-being of citizens through religion, particularly emphasizing Buddhism. The newspaper also promotes the electoral system to change from FPTP to PR under the 2008 constitution scope. They highlight the National Ceasefire Agreement and dialogue approach and invite all stakeholders to join peace talks-excluding PDFs and NUG. But the State Administration Council has been propagating PDF as the terrorists by describing that they attack the civilians throughout the country by PDF and people who attended training in the EAOs areas. In fact, the actions of SAC contract with its narratives.

From February to 3 December 2021, there had been at least 1948 battles between PDFs and the military, and an estimated 1000 battles happened within the last three months of 2021. Civilians who are against military junta support PDF directly or indirectly. Civilians support them either through direct money or by donating necessary things. People also help in donations by clicking Click to donate, playing games and others, which generate ad revenue. These ad revenues had generated considerable funds towards people defense forces. The biggest challenges for the people’s defense forces is firepower and the threat of the military’s air superiority. The National Unity Government is also struggling to equip its armed wing with automatic weapons and supplies. Due to this inability, it has been receiving several criticisms from the PDFs since the battles are becoming more and more frequent.

The international community is scrambling as well to bring peace and stability to Burma. The Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) proclaimed the ‘Five-Point Consensus’ in the Chairman’s Statement on the ASEAN Leaders’ Meeting on 24 April 2021. In summary, the Five-Point Consensus includes (1) immediate cessation of violence with utmost restraint from all parties, (2) constructive dialogue among all parties, (3) mediation of the dialogue process through a special envoy of the ASEAN Chair, (4) provision of humanitarian assistance to Myanmar through the ASEAN Coordinating Center for Humanitarian Assistance (AHA), (5) the special envoy and delegation to visit Myanmar to meet with all parties concerned (ASEAN’s Five-Point Consensus on Myanmar, 2021). The United Nations, amid statements of condemnation and calling for restoration of democracy and implementation of the Five-Point Consensus of ASEAN, Myanmar people’s faith in the UN has been on the wane due to the lack of further immediate actions and responses in place.

The consequences of the coup are striking considerable damage to the nation’s economy and many people are affected by this free falling economy. Along with massive foreign investment withdrawals, rampant inflation in the economy such as rising food prices has entailed acute cash shortages, pushing the country to the precipice of an economic collapse. Myanmar’s nascent stock exchange has plunged. Myanmar currency, kyat, has lost more than 60 percent of its value. In the current period, laborers are now at risk of their income being reduced to 3600 kyats per day on which they cannot even live from hand to mouth, let alone provide for their families.

The most notable transformation in public sentiment aroused by the revolution was the shift in consciousness of the Bamar people towards the Rohingya population and ethnic minorities, exemplified by mass social media comments apologizing to those populations for being kept in the dark about the military persecution against them over the decades.

We interviewed several people in Burma facing the struggles of everyday Burma. People include students, and CDMers. They described to us their experience from the day of the coup d’état and onwards and hustles they had to face along the way. This was an account from a 17-year-old boy recounting how he felt in the morning of February 1:

He added that he wanted to go meet his brother who was a student unionist, but his mother didn’t allow it. He told us that Burmese people were already scared even before the start. People were scared of going out in the streets, there was also a spreading rumor, which sprung from Facebook, that if people stayed still for 72 hours, the United Nations peace-keeping forces would come. This was also a proof of how social media giants are affecting the society’s response to certain things and Burma was and is still a victim of false information on Facebook. The boy fiercely told us:

The civil disobedience movements (CDMs) were the movements advocated by the activists that included officers not going to government works, students not attending schools under military appointed system, doctors not going to hospitals and covid centers. These were extremely effective towards military mechanisms but the people who were disobeying had to face all sorts of difficulties, so do people who are needing essential service during the time of global pandemic. With the covid centers closed, there are no state managed quarantine centers nor covid hospitals. Patient Numbers couldn’t be tracked anymore. Vaccine management is not transparent. There was a surge of covid patients, deaths and need of huge oxygen supply in the mid July. People were for themselves. It is only through charity oxygen supply organizations and mutual help that people got through the crisis. But in the future with new covid variants spreading across, there are no measures for safety. And with the time ticking few CDMers have returned to work for living needs. One of the former government officials who joined the civil disobedience movement and the people defense force told us that:

After joining the CDM movement, she lived in a village in Karenni state with her family. Increasing armed fighting between military and people defense forces in her village and the military’s targeted arrest of CDMers, she fled to the India-Burma border and joined the defense force by taking up the duty for fundraising and management. When junta soldiers took over her village, people including her parents and siblings had to flee to the nearest forest. From that time on, she has not seen her family, and has been struggling on the India-Burma border. Despite the hardship, she said, she believes that the people’s defense force will beat the military one day, and the winning journey of revolution will be shorter if the international communities support the Burma pro-democracy side. She added:

Another CDMer from the education sector depicted her asperity. She is the only one in her family who has positive opinions about CDM movements. Almost all of her family members phoned her several times and said “mind your own business,” she told us. Her father was a retired military sergeant and she and her sisters grew up in the military family. Both her parents are conservative could not see how much their rights are violated under the title of military principles. She eloquently stated:

Her parents called her back to return home but she said she did not want to. She told us that she already knew that they would scold me for whatever I did or will do in the future. Her parents told her that her decision was totally wrong and forced me to work back into my office. She mournfully expressed her feeling during the times:

Select Works Cited

Anonymous CDM student, interview by the author, Burma, December 6, 2021

Anonymous CDM government officer, interview by the author, Burma, December 1, 2021

Anonymous CDMer from educational sector, interview by the author, Burma, December 1, 2021

1947 Constitution of the Union of Burma.

2008 Constitution of Burma. Retrieved from https://issat.dcaf.ch/download/112205/2034666/burma-%20Burma%20-%20Constitution-2008.pdf

“Arakan Army Launches Deadly Raids on Police Posts.” Aljazeera. (January 2019). Retrieved from https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2019/1/4/burma-Arakan-army-launches-deadly-raids-on-police-posts

CNN, “Riots in Burmese History,” 20 June 2012.

COVID-19 and Conflict in Burma (2020). The Asia Foundation. Retrieved from https://asiafoundation.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/08/Covid-19-and-Conflict-in-burma-Brief_En.pdf

Hlaing, K. H. (2020, November). Retrieved from https://time.com/5910040/burma-internet-ban-Arakan/

Hlaing, K. H. (2021, August). The Diplomat. Retrieved from https://thediplomat.com/2021/08/Arakan-army-rebels-seek-inclusive-administration-in-Arakan-state/

Human Rights Watch. (2020, September). Retrieved from https://www.hrw.org/news/2020/09/01/burma-end-harassment-Arakan-media-outlets

(2009-2010). Integrated Household Living Conditions Survey in Burma. United Nations Development Program. Retrieved from https://www.mopfi.gov.mm/sites/default/files/upload_pdf/2020/08/IA2_Poverty_Dynamics_Report_0.pdf

Kyaw, K. P. (2016, May). Frontier Burma. Retrieved from https://www.frontierburma.net/en/nld-goes-it-alone-raising-ethnic-party-ire/

Lwin, N. (2019, April). “Interview with AA Chief, Part 2.” The Irrawaddy. Retrieved from https://burma.irrawaddy.com/opinion/interview/2019/04/13/188989.html

Lynn, N. H. (2018, January). Frontier Burma. Retrieved from https://www.frontierburma.net/en/Arakan-political-leader-dr-aye-maung-arrested-in-sittwe-after-mrauk-u-violence/

Myint, M. (2018, January). The Irrawaddy. Retrieved from https://www.irrawaddy.com/news/burma/9-people-reported-dead-police-crackdown-protest-mrauk-u.html

Nyein, N. (2020, March). The Irrawaddy. Retrieved from https://www.irrawaddy.com/news/burma/burma-govt-declares-Arakan-army-terrorist-group.html

Panglong Handbook: Defining Panglong Agreement, Panglong Promises and Panglong Spirit (2016).

Pwint, N. L. (2019, January). The Irrawaddy. Retrieved from https://www.irrawaddy.com/news/confederation-option-Arakanese-people-aa-chief-says.html

Radio Free Asia. (2021, June). Retrieved from https://www.rfa.org/english/news/burma/citizenship-06042021204200.html

ReliefWeb. (2020, October). Retrieved from https://reliefweb.int/report/burma/burma-election-commission-lacks-transparency

Stockwell, A. J. (1998). Conceptions of Community in Colonial Southeast Asia. Transactions of the Royal Historical Society, 8, 337.