This paper is about a rather strange refugee experience, that of the Greek refugees from Turkey who, in 1923, were obliged to leave their home and property and travel all the way from Turkey to Greece. Through the story of my great grandpa Zacharias, I tried to examine the story of the Pontic Greeks, who found themselves between a new reality, in mainland Greece, and their struggle to preserve memory of their birthland in Pontus. Their story is interesting because they were a part of the compulsory exchange of populations between Greece and Turkey, through a treaty that left those people no other choice[1]. It is also fascinating because of the way they managed to combine their two identities, the Pontic and the Greek, loving at the same time two homelands. Many of those refugees settled in villages in Northern Greece. Specifically, my ancestors settled in Agistro village, at the province of Serres.

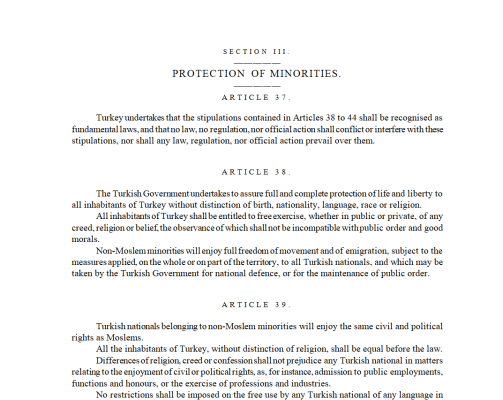

The Treaty of Lausanne

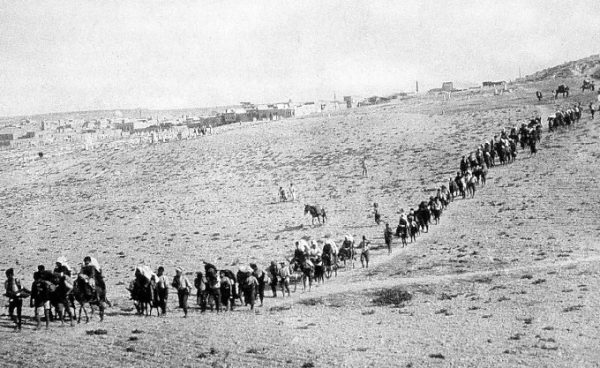

In July 1923, the Treaty of Lausanne was signed, as a final act to end the state of war between Greece and Turkey in the Minor Asia. The war in Anatolia was a product of its time –Turkey fought to uphold its sovereignty and to create a homogenous political entity, trying to transform an old empire into a modern nation state as an answer to Greek demands and fight over their so-called ‘fair rights’ in regions of Anatolia, such as Smyrna or Constantinople. While Greece tried to expand its limited borders in Anatolia, Turkey had to defend its territory, so the outcome of their collision was a massive refugee movement back and forth between the two countries. What was significant about this Treaty was the unprecedented decision to grant the compulsory exchange of populations as the only practical solution and the only guarantee to maintain peace. The Treaty of Lausanne, when signed, solely established and certified an already existing status in Anatolia of violent transfers and persecutions, implied ethnic cleansings and general aggressive policy towards heterogeneous ethnic entities. The Greco-Turkish War of 1919-1922, known in Greece as the «Minor Asia Catastrophe», reached its climax in 1922 when the Turkish army launched its offensive, pushing the Greek army to a constant retreat. A large great group of the Christian population followed the fleeing Greek soldiers while the Turkish forces set fire on the Christian quarters of Smyrna leading to the exit of many refugees that reached the shores of Greece[2].

Northern Greece

The Pontic refugees that left from the region of Pontus are recorded to be 182,169[3] –the majority settled in rural areas near the borders with Bulgaria and Yugoslavia. The internal “Colonization of Macedonia” was an excellent opportunity to settle refugees in arable lands so they would have productive employment, as most of them were farmers, but also to reassure them by allocating lands upon them as a factor to spread radicalism amongst them. Moreover, the ethnological change in Northern Greece prevented neighbor states to pursue any ethnically justified territorial claim. Refugees in Macedonia were settled in camps, public buildings, storehouses, generally supported by world organizations[4]. Regardless all of the political considerations harbored by the state, thousands of people left their houses, properties, employments, animals and took the long journey to Greece. The arrival of so many refugees was a shock to local communities, the defeat in Anatolia was indescribable but, also, Greece only targeted in freeing their brothers and sisters in Minor Asia and regaining the historical Greek territories and was definitely not ready to host so many economically destroyed refugees.

To note, Greece was already in turbulence, its financial state was not capable to support this arrival, as it was a classic, post WWI weak economy, while soldiers’ and civilians’ morale was low and there was a political struggle between King Konstantinos and Prime Minister Venizelos. On top of that, locals were obligated to pay taxes, open houses and farms to host refugees, gather food and clothes. We will not focus overly on the hostility, offence or repugnance of the natives because in our research such examples were not distinguishingly remembered or mentioned. It is just necessary to note that the ‘long Greek brothers and sisters’ of Minor Asia were not exactly welcomed as such, but we cannot also ignore the difficulties Greece already faced.

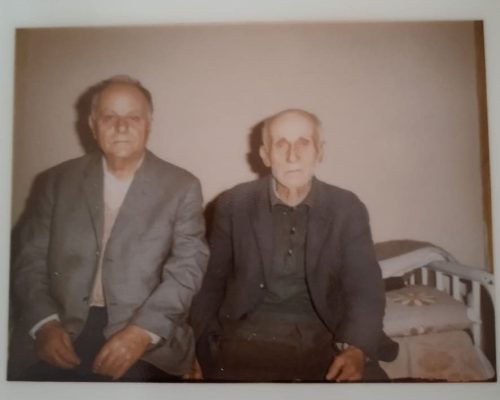

Story of great grandpa Zacharias

The life story of my great grandpa Zacharias is a great example of a Pontic refugee in Greece regarding the exodus, the arrival and the aftermath. For the purposes of this research, I had conversations with my grandpa Dimitris and two other elderly men in my village Agistro, grandpa Iordanis and grandpa Milonidis, that their families traveled and settled in the village Agistro at the same time with my great grandpa. He was from a village in Pontus called Fatara, near the town Erbaa. He then embarked to Greece in 1923 and he arrived in Kalamaria, Thessaloniki, where most refugees were settled in camps, in order for the competent authorities to check their papers and health condition and organize their distribution. Great grandpa Zacharias came from a family of nine boys and three girls and they all arrived in Greece safe and sound. Grandpa Zacharias was born in 1909 on papers, but grandpa Dimitris, his son, says he must have been some years older, without knowing the reason, but assuming it had something to do with the legalities of his departure or resettlement. They spent approximately six months in Kalamaria, a district of Thessaloniki. Kalamaria is remembered by most of the refugees as an ugly area, full of mud and surely they did not want to stay there. My informers confirmed that, but did not say anything more about this first stop. Most probably, they do not know because their parents never mentioned anything particular , although many testimonies point out that refugees’ arrival was not well prepared as well as not very welcoming.

What had be done next was to find a place to resettle. Great grandpa Zacharias with some two or three other men, one of which was his cousin, travelled to some villages in Serres province until they met the army that advised them to stay put in Agistro. Eventually, the rest of their families moved there. My grandpa Dimitris said that ‘it was the welfare services’ who pointed them where to settle, which is where vacuumed houses and spare land were available. All this empty space was created by the departure of Muslims (Turks) during the exchange of populations. Their properties were requisitioned for the purposes of the housing of the refugees as it had happened to the Greek refugees’ properties in Pontus and Minor Asia. Although, a common complaint among the refugees and their descendants is that the land, animals and tools they received by the Greek state were not comparable to what they left in Pontus. My grandpa Dimitris often says with grievance:

Grandpa Iordanis adds to this complaint that the lands were:

Many of the refugees travelled through the area of Thessaloniki –Serres –Drama only to beg for some food until they settled and found a job. I believe this is something grandpa Iordanis mentioned as a detail that indicated the dispassionate reaction of Agistro’s natives towards refugees. Grandpa Lefteris says that:

Greece, despite incidents of harsh reactions or discrimination against refugees, is loved and respected by the refugees. The exile and fighting in Pontus caused many paybacks and one of great grandpa’s brother, Captain Giorgis, avenged Turks for the violence against a pregnant women while being a captain in the profession, having some previous troubles, was wanted and was the main reason my family changed its last name!

The refugees spent some time living in others’ houses as guests or workers until the state allocated them land, repaired or built houses or until the refugees gathered some money to start their life. Great grandpa Zacharias lived for one or two years in a widow’s house as a worker. This proves that locals were rather neutral regarding this new situation of coexistence, but they did not want to push it any further and establish closer relations with the refugees. This widow’s daughter, grandpa Dimitris says, was in love with great grandpa Zacharias but her family asked her disapprovingly ‘you want to take a refugee?’, so nothing happened between them. Eventually, my grandpa married a refugee Pontic girl, great grandma Anastasia, that travelled from Amasya and resettled in nearby Ano Karidia, Serres.

Around 1925 the program for the settlements took shape and the first ‘nucleuses’ were erected. Nucleuses were the houses destined for the refugees and were founded from the central clock tower of Agistro village and below. At first, it was a dense area of houses built very close to each other and as a result many families lived together. Grandpa Lefteris said that: ‘Grandpa Zacharia’s house had only a living room and the bedroom. But grandpa Zacharias was a good householder and managed okay. Very hard –working. He did no harm to no one, everyone says that, not me, whoever met him. He was a good barba!’. And I come to wonder, how could one not be hard –working and easy to live with, when he had lost everything and tried to live in peace and fit in?

However, as time passed, some houses became stables and storage houses, the yards got larger and the houses were modified and improved. But that happened after World War II, which was another great shock to the refugees that were obliged to move again. The ‘German War’, as it is called by this generation of Greeks, vanished all the differences between ‘refugees and locals and created the division between communists and patriots’, as all of my informers said. This is an obvious reference to the Greek Civil War (1946-1949), whose origins hark back during the Occupation of the country (1941-1944) by the Axis forces. World War II is a turning point in history and memory of the Pontic refugee community. Pontic refugees capitalized on the shifting political priorities of that time: being a Pontic became a honorable identity and they became recipients of relief aid. Refugees had to relive the same situations of evacuation and war all over again, although sometimes meeting other Pontic soldiers helped them stay safe, find some bread or pharmaceutical aid.

This generally generated and formed a solid, proud Pontic identity of survival and comparison. Some of them had not completed their homes yet and many still worked to improve their fields and generally restore their life after the Minor Asia Catastrophe and already faced another catastrophe. Grandpa Iordanis’ dad said to him ‘Do not go outside to see, do not act like we did in Turkey’ while German armies walked through the village. Families had to relocate again and move their belongings and animals with carriages or by foot through the mountains because my village’s geographical position was crucial for the war. Some accommodated in others’ houses, natives’ or Pontics’, relatives or not, and some were at the appropriate age to join the war. Families were lost and met again years later. Grandpa Dimitris, Iordanis and Lefteris all stated that ‘Pontics resettled two times’, including themselves, while the entire Pontic population fought, resettled and lost their relatives and properties twice in twenty years. What is very representative of the way they moved, is that they tried to stick together. Grandpa Lefteris informed me that: ‘With your grandpa we were together in all the resettlements. And from Turkey. Our elders fought together in Turkey and then, me and your grandpa were together in the German War and during the Civil War and then we came back to Agistro together’.

My grandpa Dimitris often recalls this encounter he had on a train from Athens to Thessaloniki, around 1970. On this route, he ran into a man from Constantinople and they spent the entire time talking to each other. The interesting fact is that they both felt very familiar with each other and came to question whether they were lost relatives. The most interesting fact is that my grandpa always mentions that this man looked alike his mother’s brother, who was lost during the 1923 exchange. My grandpa knows how this lost uncle looked like because another relative was said to be similar in appearance with this uncle! Unfortunately, my grandpa could not visit this man in Constantinople because he never had the money or the time to do so. Nevertheless, this story always makes me think about this vacuum in their hearts and the expectation of meeting someone hoping he is a relative. I believe this is s habit many Pontics have and it is quite logical, considering the amount of relatives they lost during the wars.

Pontic Identity and Integration

Leaving Pontus, seems to me, like a shock inherited through generations. I believe an appropriate way to understand and describe the Pontic identity is that it is an ethnoregional identity[5]. This means that the identity is not either solidly national nor ethnic. Firstly, the group is a part of a wider, Greek, nation and secondly, the geographical reference of Pontus has been lost. The collective memory of the Pontic Hellenism shares common memories and cultural affinities that has shaped generations into being very close to their roots in Pontus, their “lost but not forgotten” ancestral land, but also love Greece as their home. That feels to me, like a way to cope with the new reality. Pontus, as a birth land, was lost for good. We have to not forget that nation states fought for homogeneity and refugee groups always do not add up to the expectations of the nation state. Pontics felt Greek, they were Christians and they fought alongside with the Greek army, however their home was Pontus and they fought with the expectation of staying there. My grandpa Dimitris, and generally my informers, talk about Pontus with love and nostalgia, although they never lived or visited those places but heard stories, limited but still, and tried to learn and talk the Pontic dialect. However, everyone notices that first generation refugees did not talk much. Surely, it was painful and stressful to talk about what they lost. The way they lost their homeland was brutal but I feel like this silence helped them remember the good and put aside the bad. Also, sometimes it was tricky to reveal your identity and refugees wanted to protect themselves and their children from discrimination.

The main dispute and accusation against Pontic refugees was that they were not “Greek enough” and they were derogatorily called “Turks”. In my village, these kind of comments may not have been common, but they were heard everywhere. Therefore, parents payed great attention in educating their kids, also learned themselves to speak Greek fluently and did not talk in the Pontic dialect, except privately in family level. An informer noted that “Don’t you notice that most Pontics speak Greek better? I think it’s because our elders insisted on us going to school. Natives didn’t care so much about their kids’ education”. Often, many groups were either obliged or chose not to speak the Pontic dialect but they kept their cuisine and folk dance alive. They maintained many Pontic songs and traditional instruments, such as the “kementzes”, the pontiac lyre. Next generations also wrote and sang many songs dedicated to their lost home. What seems to me kind of strange, is the fact that although many elders did not talk much about Pontus and tried so hard to prove their “Greekness”, managed somehow to pass all this love about the lost homeland onto their children and so on. It is remarkable in such desperate times, to keep memory alive, even if it is through a recipe done every Sunday or through a song sang in every wedding.

New generations are more brave to face, explore and maintain memory and history. Pontus is still somehow the original point of reference, but Pontics are now integrated into Greek society and there is no longer any question about being “Greek enough” or not, neither is there any hostility or repugnance towards them. One hundred years after the Minor Asia Catastrophe, seems like a great time to uncover stories, educate ourselves and preserve the history of our ancestors, their culture, their tradition without being afraid of discrimination or marginalization. It is also interesting to research how traditions and cultures mix up, cross-fertilize each other, like something that always transforms and represents a wider group of Pontic descendants or non –Pontics who are interested in this history.

Sometimes, people get stuck in the middle of great transitions and alterations in history but these people are actors of this history and not exclusively its victims. We cannot homogenize all types of refugee experience. Through my bibliographical and oral history research, they seemed at times very oppressed and doomed, but for a group of people that were lost and found twice in a twenty year period, they did quite okay.

Citations:

[1] The other exchanged population were the Muslims of Greece, that were obliged to travel to Turkey.

[2] Zurcher J. Eric, Turkey: A Modern History, London: I.B. Tauris, 2004. Stavrianos, L. S., The Balkans since 1453, London: C. Hurst, 2000, 582-591.

[3] Maria Vergeti, “Ethno-regional identity: The case of the Pontic Greeks”, PhD diss., Athens, Panteion University, 1993, 54 (in Greek) and Elisabeth Kontogiorgi, Population Exchange in Greek Macedonia: The Rural Settlement of Refugees 1922-1930, New York: Oxford University Press, 2006, 111.

[4] Ibid., 92, 112, 121-124, 141.

[5] Vergeti, “Ethno-regional identity”, passim.

Bibliography:

- S. Stavrianos, The Balkans since 1453, London: C. Hurst, 2000.

- Elisabeth Kontogiorgi, Population Exchange in Greek Macedonia: The Rural Settlement of Refugees 1922-1930, New York: Oxford University Press, 2006.

- Maria Vergeti, “Ethno-regional identity: The case of the Pontic Greeks”, PhD diss., Athens, Panteion University, 1993, (in Greek).

- Zurcher J. Eric, Turkey: A modern history, London, I. B. Tauris; 3rd edition , 2004.