An event, when recounted by just one person, is their fate.

But, when recounted by many, it is history.

And this is the hardest of missions:

to reconcile the two truths- the personal and the universal.[1]

Svetlana Alexievich,

Voices from Chernobyl: The Oral History of a Natural Disaster,

Picador, 2006

Introduction

The island of Cyprus lies in eastern end of the Mediterranean Basin, sheltered to the North by the Turkish shores and to the east- southeast by the shores of Syria and Lebanon. Cyprus is populated by two prominent ethnic communities, Greek Cypriots and Turkish Cypriots. It was under Ottoman rule for three centuries, between 1571 and 1878, the year when it was placed under British administration. It was subsequently formally annexed by the UK in 1914. After the British rule was implemented (1881 census data), there were 342 mixed, 342 Christian and 114 Muslim villages in Cyprus[2].

During their rule, the British kept in place the ottoman administrative “millet” system, a form of autonomy and self-governance of communities on the basis of their faith (discerning between muslim and non- muslim populations) institutionalizing communal representation in various political bodies. This form of separation between the two ethnic communities precipitated the transformation of ethnic-religious identities (Christians and Muslims) into national ones (Greeks and Turks) respectively; starting as early as the 1920s, these national affiliations were solidified by the end of the first half of the twentieth century. Historically, relations between the two ethnic communities were mainly smooth, albeit small skirmishes of violence. At the same time, the tendency for separation and divergence between the two communities that was ever-present, was also expressed in separate intercommunal agricultural, political, social and cultural formations.

During the 1950s the development of distinct “national consciousnesses” was sped up by the possibility of the British withdrawal. Both communities advocated for ‘Enosis’ and ‘Taksim’ respectively. ‘Enosis’ embodied the wish for the whole island to be annexed by Greece, whereas ‘Taksim’ (meaning ‘Partition’ in Turkish) supported the permanent division of the island in Turkish and Greek portions. Armed guerilla organizations were founded to advocate for these nationalistic narratives (EOKA, TMT)[3], while officially they were resisting and undermining the British rule. Political leaders in both communities (as well as political leadership in Greece and Turkey respectively) supported these organizations, both actively and covertly. 1958 marks the escalation of inter-communal violence, when the British engineered the physical division of the capital Nicosia for the first time. Communal markets were split and lines between ‘Greek’ and ‘Turkish’ neighborhoods began to be more definitively outlined in a climate of fear, suspicion and threat, giving way to nationalistic hardliner narratives.

On August 16, 1960, Cyprus attained independence after the Zürich- London Agreement (1959), as one state consisting of two politically equal communities and became a member of the UN. The Zürich- London Agreement attempted a balance between interests of Britain, Greece and Turkey, excluding both ‘Enosis’ and ‘Taksim’ from the public political discourse. Although this presented a new set of opportunities for intra-communal coexistence, it was wildly sabotaged by leaderships in both communities letting rather small armed paramilitary groups act unmolested. At the same time, Cyprus’ actual independence was undermined by the Greek and Turkish state respectively (both officially and unofficially– by channeling material and human resources to paramilitary groups).

This contrived animosity, fueling the inter- communal conflict from 1963 to 1967, combined with the unyielding nationalistic stance of the Greek military junta (ruling in Greece between 1967- 1974) led to the culmination of the Cyprus conflict and the division of the island. In July 1974, the boiling point of the conflict, the Greek military junta backed a military coup against Makarios (President of the Republic and undisputed leader of the Greek Cypriot community), which in turn led the Turkish military to intervene and land on the northern part of the island in order to protect the Turkish- Cypriot population. The Turkish army’s occupation caused a great movement of populations, violently displacing great numbers of both Greek Cypriots to the south (180k) and Turkish Cypriots (90k) to the north respectively.

These devastating developments gave the island its current appearance, namely the dividing line between the Republic of Cyprus (southern part) and the Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus (northern part). This ‘Green Line’, splitting the capital of Nicosia in two, was designed in 1963 by a British military officer as a temporary ceasefire line separating the armed groups of the two communities. After 1974 and the population displacements, Nicosia remained the only divided city in the country, until the ceasefire line was extended eastward and westward, dividing the whole of the island in two. Officially the ‘Green Line’ is not recognized as a border but it is rather regarded as a ceasefire line, marking the ‘free’ from the ‘occupied’ areas[4].

The imposition of the ‘Green Line’ cemented the island’s division on an ethnic basis, essentially obliterating any contact between the two communities from 1975- 2003. The geographical dichotomy was absolute and moving from one part of the island to the other was impossible. Up until 2003, each side of the island was known only through narrations of displaced persons to the other side, describing their lived experiences from before 1974. Subsequently, there is a whole generation of Cypriots (on each side of the border) that grew up with this division as a given, unable to get to know the other community, as well as the rest of the island, in conditions of absolute segregation. The Green Line has divided both space and time and has damaged individuals’ identity[5]. Ever since its imposition, the two communities took totally divergent courses. The vast majority never met a compatriot from the ‘other’ community. There was absolutely no contact between them, no news circulating regarding the other side, other than totally state propaganda[6]. Ioannou, in his latest work about the normalization of Cyprus’ partition (Palgrave Macmillan, 2020), quite eloquently describes this situation (absence of intracommunal contact) as an “echo from the dead zone, an echo where each community heard back their own voice[7]”. From 1974 onwards, the Turkish Cypriot community’s existence was totally stripped from the Greek Cypriot public narrative- and vice versa.

In 2003, just a year before the Annan Plan referendum[8], the authorities of the Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus opened several checkpoints along the Green Line. For the first time in decades, the division line, the line between “us and them” was no longer “impassable”[9]. Since 2003 and the opening of the checkpoints in Nicosia, Turkish Cypriots and Greek Cypriots became once again gradually naturally visible to each other. This event marked the biggest and most important development in recent Cypriot history since 1974, since both communities gained access to the other side. The mass movement of populations from either side to the other was unprecedented in size and intensity, lasting for months[10]. From 2003 to 2005, five checkpoints were opened in different spots of the ceasefire line. These checkpoints are included in the EU’s Green Line Regulation (Council Regulation 866/2004), as part of Protocol 10 (on Cyprus) of the 2003 Act of Accession- Cyprus’ act of inclusion in the EU.

This “momentous event”[11] of the opening of the checkpoints had a notable impact on intra-communal relations and on people’s perceptions of Cyprus and the Cyprus problem[12]. It is estimated that during the first three months 200.000 Greek Cypriots crossed to the north through the newly opened checkpoints[13].

By conducting interviews with members of both communities (Turkish- & Greek -Cypriot) who had not formed their own lived experience of the 1974 incidents and only formed their experiences and perceptions on an island already divided, we can examine if and in what way was their perception of the ‘Other’ shaped by collective memory passed down by elder generations and whether the opening of the checkpoints and the reestablishment of contact between the two communities affected their perception of the ‘Other’, which is important because it can resonate with the ongoing debate of whether there is realistically room for the peace and reunification movement’s requests for a political settlement of the Cyprus problem along the lines of a federation state scheme (Bizonal bicommunal federation (BBF). The premise was that this liberating experience had compelled people into actively pursuing the island’s reunification, not only by changing their perception of the other ethnic community, but rather that this change would be reflected in policies of both communities’ leaderships, inspired and required by the people.

I chose to interview people aged 25-55 from both communities, who did not live through the imposition of the ceasefire line and thus possess no lived memory of the events leading to the island’s division. It was especially daunting to find participants willing to take part in this research, while going through a pandemic. I resorted on one hand to the help of Social Networks and specifically the Twitter community where I mainly encountered my Greek- Cypriot interviewees. The Turkish Cypriot participants were introduced to me through a Greek Cypriot professor of mine in the university, whom I thank for his instrumental help. Meeting with members of the Turkish Cypriot community willing to take part in my research proved quite challenging, mainly due to the language barrier, as I speak no Turkish at all, as well as due to a general hesitation on their part. Their number may seem too small to make a difference (only two interviews), but their experiences and insight proved invaluable in presenting a much overlooked and otherwise unknown side of history. Beyond the interviews, the backbone of my research was G. Ioannou’s recent book, (The Normalisation of Cyprus’ Partition among Greek Cypriots: Political Economy and Political Culture in a Divided Society, Cham: Palgrave Macmillan, 2020) and a broad selection of articles and papers that sadly were mainly Greek Cypriot oriented. I suspect academic research is tilted this way partly due to the language barrier in the northern part of the island, and partly due to the lack of access to the north, until 2003.

Growing up with a border so close to home

Andreas, 33, a journalist whose father is a displaced Greek Cypriot refugee from Karavas (Alsancak) in Keryneia (Girne) District, was born to a Czech mother and grew up in Greece. His paternal family still lives in Cyprus, and he tries to visit as frequently as possible. To him, the Green Line represents a no man’s land boundary, a border in the sense that there are certain procedural prerequisites in order to cross through it. It signifies a “dead zone” between two parties “that should not have this space between them in order to coexist”.

Loizos, 36, a historian, born and raised in 250 meters from Nicosia’s Green Line, shares that from very early in his life he understood that “my known world stops right here”. His father being a civil engineer, they always had on their balcony a quickset level[14], which has a sort of a telescope on top of it. Loizos recalls zooming in Pentadaktylos mountain, gazing on the Turkish and TRNC flags etched on the mountain, as a child’s game.

Eliza, 34, an English language professor, feels the Green Line evoked a sense of impenetrability before the opening of the checkpoints. “To me, it does not signify a border, although from many aspects it functions as one. I see it as the mark from which the occupied territories begin” she says. Growing up, she loved being a listener of discussions and stories of adults. Both her parents come from the outskirts of Nicosia and she lives in Dali, which was a mixed village before 1974. Learning about the Green Line as a child, she pictured it as a literal wall dividing the island, feeling the proximity with the northern part of the island, while at the same time sensing a great divide between the two parts.

Rania, 34, who studied translation and is now working in the event industry, believes she knows very little history. She too, lives very close to the Green Line mark in Nicosia. She remembers it being there all her life, and confesses that as a child it gave her the chills, but at the same time the division line was considered something normal. To her the Green Line is not a border, but rather it stands for the utmost point of access.

She first came face to face with the reality of living in a split town, through the eyes of a classmate born in Greece, who felt boxed in. and said to her: “I feel that if I run one way the Turks will get me, and if I run the other way I will fall into the sea.” This is what made Rania herself understand how restricted her daily life could come to feel. Growing up, she came to see “the ridiculousness of it all; it was easier for me to get on a plane, visit a foreign country, while being unable to move 5-6 blocks from home”. The view from her house in Nicosia “the first thing I see every morning”, is the same as Loizos’, Pentadaktylos mountain, the Turkish and TRNC flags etched on it, lately being lit up at night too.

Umut, a Turkish Cypriot university professor, now 45, was born in Nicosia, her mother coming from Lapithos (Lapta), a mixed village on the northern coast of the island and her father from a mixed village as well, called Ayios Theodoros in Larnaca (Larnarka), having been forcibly relocated to Nicosia. “Before 2003, my generation never had the chance to cross to the south. I had never met a Greek Cypriot”.

Maria, now in her sixties, is Greek and has lived in Cyprus for almost 40 years. She now considers herself a full-fledged Cypriot, in the sense that living in Cyprus from her early twenties helped shape her as a person. “When I first moved to Cyprus in 1983, it was just 9 years after the invasion, and the family of my boyfriend were refugees from Keryneia, so all wounds were very raw at the time. There were pictures of their house and of the city they left behind all over the place”. Seeing the roads of Nicosia cut up in two by the Green Line was really shocking for her.

Moving out of this house and relationship, Maria stayed literally on the edge of the Green Line, her yard ending on the fence. She could hear the voices of both Greek- and Turkish Cypriot guards in the military outposts on each side of the line. “Only sound was moving freely about; I could hear life on the other side, but I had no images to go along with the sounds” she told me.

Kyriacos, 35, is a journalist in one of Cyprus’ daily newspapers. He lives in Nicosia, close to the Green Line. He grew up in Nicosia, and always remembers that “the city was split in two. You could not go beyond a certain point.” He says growing up in a politically liberal and humanist family, the curiosity grew inside him, to meet Turkish Cypriots, “to see who was on the other side, to experience what was unknown to me then. I had no greater curiosity than this!”. He remembers seeing the northern part of the island “only through pictures”. To him the Green Line marks an open wound, functioning as a vivid reminder that to this day “we fight for peace”.

Passing down memories of coexistence and conflict

Loizos’ maternal grandfather was the director in the reform school[15] of Lapithos (Lapta), a town on the northern coast of the island. The school, groundbreaking for its time, had a mixed population of students (Greek- and Turkish Cypriots). He remembers listening to stories from his mother where naturally both communities were represented, and coexistence was neither always ideal nor always difficult.

His father on the other hand, comes from a village near Limassol on the southern coast of the island. His stories, mainly from the 60’s, when the family relocated in the urban area of Limassol and the intercommunal conflict was in full fledge, evoked a sensation of unrest to young Loizos’ ears. At the same time, when walking through Nicosia with older members of the family, he would frequently hear stories about neighbors, now relocated (forcibly or not) to the northern part of the island. He remembers his grandmother using the word “Tourkoú” (woman of Turkish descent), while pointing to an empty house during their stroll. “The past merges with the present in very strange ways” he concludes.

On life before the island’s division, “I had a very murky view on what lies beyond the Green Line” Andreas says, and stories in the family about life in Karavas were scarce. Instead, the memory passed down to him contains few narrations on the atrocities mainly by the Greek Cypriot paramilitary organizations, as his father comes from a village with exclusively Greek Cypriot population.

Eliza, 34, admits that both communities obviously did coexist before 1974, and that “the Turkish Cypriots were part of the island”, making the classical distinction between members of the Turkish Cypriot community and the settlers from Turkey who came after 1974. What differentiates the Turkish Cypriot population from the settlers is mainly the language, as most of them -especially older people- speak the Greek Cypriot dialect, but also the settlers appear and seem different, Eliza claims, the cultural divide is bigger, they look as if they are from a faraway place.

Umut’s maternal grandmother used to tell her a lot of stories from Lapithos, about how good the relations between Greek Cypriot and Turkish Cypriot residents were, the help the women were extending each other in caring for babies or other housework. When the family decided to move after violent incidents against the Turkish Cypriot population in 1963, her grandmother recalls a Greek Cypriot neighbor pleading with her not to leave. “This kind of stories define you” she concluded. Eliza’s testimony adds to Umut’s; her family shared similar stories of neighborly relations in the mixed village of Dali. She remembers her uncle saying “we saw no difference between us; they (Turkish Cypriots) were part of the island as we are”.

From narrations in his family about life in Morfou, Kyriacos recalls that there used to be a rather good accord between the two communities, although he too admits that this was not always the case, not always and not everywhere either. His grandfather has shared stories where Greek Cypriots were perpetrators of atrocities towards Turkish Cypriots. Kyriacos attributes these events (from either side) mainly to ultranationalist elements in each community.

During the events of 1974, Loizos’ family fled their Nicosia home to stay safe, as there were clashes and fights close to the Green Line; they stayed with relatives in Limassol (to the south). While not a direct descendant of refugees, he admits surmising through the stories and the memories of elders that the feelings and experiences from 1974 were still very raw, although he claims that as a child, the fact that it had already been 11 years, seemed like a really long time had passed since.

Andreas, 33, had heard stories from his father, who fought in 1974, during the Turkish invasion. His paternal family relocated to the refugee settlement of Anthoupoli in Nicosia after being violently displaced from Karavas (Alsancak) in Keryneia (Girne) District in 1974, leaving behind their home, as well as farm properties. He remembers listening to all stories with great interest, emotion, and a sense of definite loss, but admits that he could not identify with the feeling, and mostly lived through the storytelling as an observer.

Rania, 34, is one of the few whose parents and extended family did not share stories with them, neither from before the island’s division, nor from the events of 1974, even though she has uncles who went missing during the conflict of 1974. She describes this not as a pact of silence, since her parents for example share memories between the two of them, and discuss them; it seems like a rather exclusive event, where there is no objective of passing down the memories.

As they were growing up, Umut remembers talks and stories being shared in her community, exclusively about the Turkish Cypriot experiences. “We never talked about what the Greek Cypriots went through” which is interesting on its own, since no Greek Cypriot participant demonstrated such an insight. Only after leaving to study abroad did she learn about atrocities on the Turkish Cypriot side’s behalf. “This is not to say that my community has not suffered, on the contrary, they too were displaced and lived in difficult conditions for about 11 years (1963 to 1974).” But she points out the one-sided narrative, confirming its definitive existence in both communities.

Kyriacos’ mother is a refugee, displaced at age 10 from Morfou (Guzelyurt) a city in the north, after the Turkish invasion. Her own father was also persecuted by the military junta in the south after arriving as a refugee for having resisted the coup before the Turkish invasion. He makes a point to disassociate his own perception and feelings from the ones of his mother and everyone else who lived through the island’s violent partition. He said he cannot identify with these experiences, as he is not the one who lived through them: “I can understand why they feel the way they do, but I cannot share the feeling”.

The school notebooks of Greek Cypriot schoolchildren

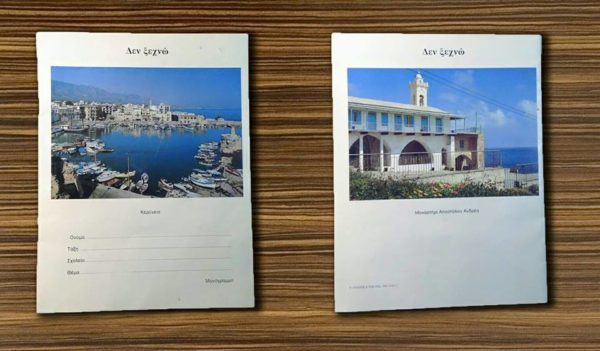

Narrations and memories of coexistence were crushed inside the Greek Cypriot school system. State funded education funneled nationalist, ethnocentric[16] propaganda to its pupils Schools are prime sites for the construction of national identities[17], as national identity is often closely related to the way history is taught in schools. Nationalism has constructed youngsters’ perceptions regarding their social identity, the country and its partition, but also about the ‘other’ community, the past and the future of the Cyprus problem[18]. The dominant narrative especially in primary schools of the Greek Cypriot side is that of invented traditions; Turkish Cypriots are viewed as a minority with feeble historical and civil rights to the island and its future.[19] The school notebooks with pictures of the occupied territories in the north, along with the very popular cue “Den Ksehno” (‘I am not forgetting/ I’m not letting go’), that were given to the children, are absolutely integrated in the reproduction of this narrative.

Rania remembers being given these notebooks, and she still can see the pictures before her eyes. Although she knew that all these pictures are from places right over the border, she couldn’t shake off the sense that they were from some faraway place, from abroad; “someplace that you would have to travel to, but then again, you cannot visit”. Eliza shared an analogous experience as well, and eloquently says, “we were actually bombarded with this information, the pictures, the sense of loss, and the obligation ‘to not let go’. These images were ever-present while I was growing up, seeing them made me want to visit all those places. Naturally, when the checkpoints opened, I wanted to see them from up close. When we crossed, my first though upon seeing those places was ‘look, they are the same as on the textbook!’” This was Rania’s words as well, “it looked exactly the same as our school textbooks It was so impressive mainly because we grew up with the belief that these were places inaccessible to us”.

Umut too recalls nationalist propaganda being disseminated through the schooling system, especially in an incident where the children were taken to visit the so-called “Museum of Barbarism”[20], which was a “pretty traumatizing” experience for her. She attributes this nationalist stance of the state to the long-standing right-wing governments in the north.

Opening up: experiences from crossing over to the Other side

Loizos remembers rumors about the opening circulating in the bicommunal groups and in the village of Pyla[21] for quite some time before the ban was lifted.

Unlike Loizos’ experience with the bicommunal groups, Kyriacos recalls being rather surprised when recounting what a momentous and historical event the opening of the checkpoints was, as there were no rumors circulating earlier.

Eliza cannot forget her desire to see the whole of the island, “up to that point it was as if the rest of the island was in some sort of limbo, like it existed and did not exist at the same time. It is a bit surreal. I was in disbelief, I kept asking my parents again and again: does that mean we can go now?”.

When the checkpoints opened up in 2003, Umut was studying in Ankara, Turkey and heard about through the news. It was a widely covered event in Turkish media at the time. “I remember reading all these emotional stories and crying until I was able to come back and cross” says Umut. “It was a relief, and it was a new thing for us. For me it was a turning point, because it enabled me to meet Greek Cypriots” she recalls.

Maria and her family were rather hesitant about crossing, mainly worrying -along with a great number of Greek Cypriots- if by doing so they were giving some sort of legitimization to the Turkish Cypriot polity. “We decided then, that no matter the administration, the whole of the island is a place for us all; Keryneia for example, I felt our steps needed to echo through those streets, our voices needed to echo in them.” Most of the Greek Cypriot interviewees reported a similar hesitation about crossing; mainly about timing- there was a sort of an unspoken pact that those who had left their homes and properties behind, the displaced, should definitely precede all others.

There were also those who decided not to cross, like most of Andreas’ family, including his father, who never visited their home in Karavas (Alsancak) after being uprooted. On the other hand, Kyriacos confesses, “I had no second thoughts whatsoever about crossing, this is my land, this is my country, not going would be like losing a part of myself; desire and curiosity is what I felt”.

Another commonplace hesitation was about not spending any money while traveling to the northern part. “We did not want it to feel like a vacation”, said Eliza. To this end, many used to pack lunches from home, fill their tanks with gas from the south and avoided overnight stays.

For Umut’s father it was really sentimental; visiting his old school and seeing his house deserted in Larnaca left him in tears. Everyone admits that for those belonging to previous generations, who lived through the events of 1974, the experience of visiting their childhood homes and towns was a rather difficult, emotionally overwhelming experience.

Andreas crossed with an uncle of his, and they went searching for the family’s old house in Karavas. They met its new inhabitants, a Turkish Cypriot woman married to a settler from Turkey. He describes this encounter as really emotional and awkward on both sides, although “the people there were very courteous, they greeted us and offered us coffee in an overwhelmingly emotionally charged atmosphere.” At the same time, he says he observed a lurking sense of ire in his relatives, fueled mostly by the traumatic loss they had experienced back in 1974.

Sevgi’s & Eliza’s grandmothers

Eliza met Sevgi and her family after the checkpoints opened. The two families got in touch through Eliza’s younger sister, when she and Sevgi took part in an exchange program for English language learners. The girls kept in touch, and after 2003, they were finally able to meet again. Both families exchanged visits, where they spoke the Greek Cypriot dialect to communicate (none of the parents spoke no English). Eliza remembers being amazed when she met Sevgi’s grandmother: “although we had already met her parents, and I had seen all we had in common, I was shocked to meet the grandmother! She looked exactly like my own grandma, she spoke exactly like her (Greek Cypriot dialect), the only thing different was her colorful headscarf- whereas my grandma always wore a black one”. Eliza admits she would never have guessed that Sevgi’s grandma was not a Greek Cypriot had she met her on the street. “I would be sure she couldn’t be anything else.”

The women’s bazaar

Maria too shared a very special experience she had upon crossing. She really wished to walk the full length of Ledra street (traditionally the main shopping street of the capital) which was also cut in two, ending on the northern side of Nicosia, on a building called “To Pantopoleio”[22]. She had heard stories from elderly neighbors, that, up until 1958, there used to be a makeshift weekly market on its entrance, were the vendors were exclusively women, hence the term “Gynaikopazaro” (the women’s bazaar). Every Friday, women from Nicosia and villages close by, gathered all around this building and set up their market stalls to sell or exchange produce, embroidery, hand- woven textiles, homemade goods and delicacies. Along with her husband, they walked the length of Ledra street beyond the checkpoint and came to the “Pantopoleio”. They entered this vibrant street market, and wandered through the stalls. “Suddenly we came to a deserted part of the market, where the stalls were closed. There was only an older man there, and he seemed busy with something[23]. Passing before him, we heard him speak in Greek– Cypriot dialect, telling us, in a rather familiar and playful tone: ‘you could at least have greeted me with a ‘good morning’. “We were dumbstruck”, recalls Maria, and felt the need to apologize to the man for not thinking he might be speaking Greek Cypriot. He was called Enver, a Turkish Cypriot from Dali (a mixed village close to Nicosia in the south), and when they started talking, he turned out to be a very good friend of her husband’s uncle in Limassol back before the ‘60s. Unfortunately, the two men did not manage to meet after all these years, but Maria and her husband had a chance to experience a very emotional encounter, abridging past and present.

Beyond the many snapshot stories of meetings, feelings and experiences, some themes seem to pop up repeatedly throughout each participant’s narrations. The long, winding lines of cars and people waiting to cross from the south to the north is an unforgettable image, and one confirmed by many interviewees at that. Rania says “it was a long wait in the car, to go through the necessary checks”.

Among stories by those who decided to cross, I sensed a common pattern; almost all participants described the land as means of identity; that the wholeness of the land functioned as a self- completing experience, what has also been defined as a “sensorial experience, an experiential, embodied sense of identity”[24]. Suddenly the land presenting as one unit again, gave these young people an unprecedented sensation of fulfilment. Upon crossing, Loizos says “You suddenly get the feeling that space has grown”.

Most participants recall a strange feeling after crossing, an oxymoron of being at home and visiting a new unknown place all at the same time. Others described it as a sense of familiarity in an unfamiliar place; a place that was not empty until then, but rather populated, and weighed by other peoples’ histories and experiences.

Another common theme was the shock one gets when they cross- experiencing first hand an array of antitheses, merging two totally different realities. Many Greek Cypriots attested that “time had stopped in the north”, “it was like entering another era”. Living conditions in the north were marked by visible signs of poverty, such as old, unmaintained edifices. On the flip side, it was equally shocking for the Turkish Cypriots who crossed into the south: Umut openly admits “We got the shock of our lives, 15 minutes from home we saw an entirely different world! It was a pleasant, shocking and sad experience at the same time”, regarding the south being much more modernized and affluent than the northern part of the island.

Beyond the emotional aspect, when asked about what changed in Greek Cypriots’ daily lives after the opening, Andreas’ opinion was rather cynical. “Nothing much I guess, they just had access to cheap gas, dentists and shopping”, while admitting at the same time, that Turkish Cypriots got the better end of the bargain, “gaining access to better employment offers and cash flow; it was purely a financial decision.”

By the participants’ impressions after having crossed, I gathered two important takeaways:

- the dominant Greek Cypriot narrative about them being the aggrieved and weaker link in history was toppled- mainly due to the flagrant economic inequality between north and south

- all of the Greek Cypriot interviewees reach a common conclusion about the “other” community. They are “like us, Cypriots”.

Growing up with freedom of movement

Ilgın, now 27, a Turkish Cypriot currently living in Greece, was obviously very young (9 years old) when the checkpoints opened, and in that sense, her lived experiences were mostly defined by this newfound freedom of movement. She grew up in the northern part of Nicosia with her family. Her mother comes from a mixed village in the north, thus speaking also Greek with Ilgın’s grandparents at home, “especially when they did not want us to understand what they were saying”. Through that, Ilgın says she experienced ‘second-hand’ the consequences of the two communities’ coexistence. “I knew people used to live together, I knew the ‘other side’ existed, but in my family, they were not talking much about it”. Her father on the other hand, comes from Larnaca (Larnarka), a city on the southern part of the island, thus presenting the other side of the story of displacement. His family, parents and five siblings, crossed to the north not as a unit, but rather tumultuously; first the mother with two children, another sibling on their own as they were of age, the father last. Ilgın’s paternal grandfather also speaks Greek and recounts that in Larnaca there were separate neighborhoods according to one’s ethnic origin[25]. Her father remembers collecting bullets as a child from the streets in Larnaca each morning after the night’s clashed between armed groups from each community during the 60s. The Turkish Cypriots who left their homes in the south, were subsequently installed in abandoned properties of Greek Cypriots who in turn had fled the north.

From 2003 and the opening of the checkpoints, Ilgın remembers a rather jubilant atmosphere as a child. She recalls having a rather strange feeling, hearing Greek being spoken for the first time outside her home and her family during the visit of Greek Cypriots in the neighborhood. A very interesting aspect of the opening in 2003 is what one would describe as ‘courtesy calls reloaded’. Families who left their homes behind (in the north as well as the south), could now meet with their houses’ new owners for the first time. In many cases, this sparked new friendships, and visits were exchanged on a regular basis (such as Eliza’s and Sevgin’s example above). A family from the north for example, welcoming Greek Cypriots who had left their home, and then, the Greek Cypriot family would invite the Turkish Cypriots for a visit in their home in the south. And vice versa; displaced Turkish Cypriots visiting their old homes in the south, and meeting with the current Greek Cypriot owners, who then would visit the former in the north.

Ilgın traveled to Larnaca with her grandmother for the first time, and still carries the image of her tears clear in her memory. Concerning her paternal family, her grandfather was adamant about not crossing in the beginning and only much later decided to cross, some 6 or 7 years later. She points out an oxymoron in his views, where he states “it is impossible to become friends with the Greek Cypriot” while at the same time he reminisces that their coexistence in Larnaca was peaceful and smooth. This internal antinomy is not unique, but appears in narrations of both Greek- and Turkish Cypriot interviewees, not only as stories passed down to them by older members of their family, but also as part of their opinion. Eliza, despite her awe- inciting experience with her Turkish Cypriot friend’s grandmother, and the familiarity she felt, stated a similar reservation.

When she was 12, she went to high school in the southern part of Nicosia, and thus she used to cross the border daily to go to school. While she herself did not encounter any problems in going to a mixed school, there were incidents in her first years where Greek Cypriot parents collected signatures to ask for separate classes for Turkish Cypriot children so as to keep Greek- and Turkish Cypriot pupils from intermingling. She left to study abroad, but plans on returning.

Is there a common Cypriot identity unifying the two communities?

The opening of the checkpoints in 2003 was generally regarded as a hopeful development. It was believed that as Cypriots on both sides gained visibility and each community familiarized with the other, Cypriots would find it possible to move forward towards reunification. So far, the divide materialized by the Green Line has proved impervious[26]. The process of division in Cyprus started long ago, and has continued unabated ever since. The once porous social boundaries between the religious communities in Ottoman times, transformed through the years, following the island-wide division in 1974, while ethno-national ideas were deeper and deeper entrenched, dominating the narratives at both sides[27].

Most participants gave positive answers, making the clarification that such commonality is better discernible in older generations. Both Ilgın and Eliza for example said the same thing about their friends’ grandmothers looking the same as their own. “When I saw Sevgi’s grandmother, she looked exactly the same as mine, only her scarf was different” says Eliza, and Ilgın “older people are more alike in the two communities; when I met my Greek Cypriot friend’s grandmother, she was like mine. There was and there is common ground, although our generations are in more ways different. You can see the difference in our generation, but not in our grandmothers’”. As Madeleine Leonard puts it “sameness and otherness become two sides of the same coin and national identity constructions are full of inconsistencies and contradictions”[28].

This divergence is mostly due to the island’s division and lack of any sort of communication for almost 30 years, which compartmentalized each community in their own impermeability. Loizos directly points to the partition as the cause for lacking familiarity with people and places in the north.

“We have a lot in common, but politics on each side complicate the matter” Eliza says. The consensus between all participants is that coexistence was crushed through the rocks of nationalism. Ilgın characteristically states, “The Greek Cypriots are much more nationalists than us, there is no comparison. On the other hand, we (Turkish Cypriots) feel a lot more helpless, like it is not us who are deciding for ourselves, because we still have the Turkish army on our land, and our government is basically a straw government, and we cannot shake the feeling that Turkey will never let go of us”. Such a bold statement, coming from a young adult belonging to an ethnic group as underrepresented as the Turkish Cypriot community in academic research, has an important resonance of the Turkish Cypriot’s popular feeling, something to ponder on, the victimization process of peoples by state authority. Speaking with another Turkish Cypriot, I heard another sort of radical opinion. He claimed that Turkish Cypriots are nowadays the only ethnic group in the EU whose right to free movement has been suspended (once again during the time of the pandemic- as the checkpoints were closed in an effort to halt the pandemic from spreading).

In lieu of a conclusion -Can the Cyprus problem be solved?

The “Cyprus problem” has defined Cyprus in the public sphere. One cannot think of the island without pondering on the how’s and why’s, while its history, its division and future take up most of the conversation around it. When asked, Ilgın rather pessimistically said she didn’t think so, although she wishes “we could all live together” -a common place in all interviews. According to a totally unfounded optimistic view, a solution along the lines of a “consociational democracy”[29] could work in Cyprus as it would in general, in cases of countries deeply divided by national, ethnic, or religious factors. In such schemes, minority populations possess a greater percentage of political power and participation than would normally correspond to their absolute numbers, in order to feel safe and respected while coexisting with greater communities in said state formation. An administration scheme along those lines (weighed representation) was supposed to be implemented in the 1960s, after Cyprus gained its independence. It was practically never tested in action though, as at that time, it was wildly sabotaged even by Makarios himself.

Intentionally, I made a point to pose an open- ended question to all participants: what would be the ideal solution to the Cyprus problem for each one of them. The word ‘federation’ was the one I heard most, and all seemed to agree that this was the only feasible way forward. At the same time, in a quite self-contradictory admission, most participants were indeed rather unhopeful and pessimistic when talking about a possible solution due to nationalism and geopolitical interests in the area, a view shared by most scholars as well. However, all participants outlined the need and desire for coexistence, which makes the discrepancy between current political realities and the peoples’ needs and wishes all the more visible.

There is -in a sense- no going back to the times of blanket division. The experiences from 2003 onwards make sure of that. What is however undisputable, is that jubilation and enthusiasm alone were not enough in shaking off deeply embedded stereotypic views of the ‘other’ in each community. Coexistence might have been the norm in the distant past, but the younger generations grew and matured with no direct memory of it, in a different daily reality, one where the norm is a divided land.

Gradually though, the excitement of crossing, of meeting the Other, abated. The Annan Plan referendum had much to do with this development, as the Greek Cypriots’ rejection ultimately reanimated the island’s divided existence. To this day, the question very much remains as to why the plan was so widely rejected. It might be helpful to note that all political parties in the south, even those of the left (communist and socialist) more or less openly supported a negative vote.

Ultimately, although opening the checkpoints and reestablishing direct communication between the two communities was undeniably a positive development, its effects were cut short by the Annan Plan’s rejection. On the other hand, there is a well- founded belief that this potential has still much to produce in terms of this reinstatement of contact and maintaining a rapport between the two communities. Despite their quite dark predictions, most participants left me with the impression that this process of reacquainting themselves has yet to reach its full potential.

The pandemic came to deteriorate this situation. Leaderships in both north and south of the Green Line, used it as a pretext to shut down free movement between the two communities. In February 2021, this sparked a grassroots movement in both sides of the dividing line, where Turkish- and Greek Cypriots –each on their side- took to the streets to demonstrate against authoritarian state measures under the motto “Os Damé” (That’s enough). The movement gathered the largest crowds in Cyprus in a very long time, protesting also state corruption and asking for a united federal Cyprus. Loizos and Kyriacos where among those who took part, in agreement with the movement’s imperatives. There was no corresponding political expression in the parliamentary election that came shortly after, in May, mainly because it gathered supporters on the left of the political spectrum.

Despite the discouraging reality, Cypriots deserve to share a common future, in an undivided land. The ground broke in 2003, and this newfound freedom of movement, this rapprochement, could work as the bedrock upon which the pillars of reunification should be built.

[1] Translated from the Greek edition of the book

[2] Nicos Peristianis & John C. Mavris, The “Green Line” of Cyprus: A contested boundary in flux, Aldershot: Ashgate, 2011.

[3] EOKA was the Greek Cypriot group (Ethniki Organosis Kyprion Agoniston – National Organisation of Cypriot Fighters) and TMT was the Turkish Cypriot one (Türk Mukavemet Teşkilatı – Turkish Resistance Organisation).

[4] Nicos Peristianis & John C. Mavris, The “Green Line” of Cyprus: A contested boundary in flux, Aldershot: Ashgate, 2011.

[5] Copeaux E. &.Mauss-Copeaux, C., “Dividing Past and Present, The Green Line in Cyprus 1974-2003”, in State Frontiers: Borders & Boundaries in the Middle East, Edited by Inga Brandell, London & New York: IB Tauris, 2006

[6] Ioannou G., The Normalisation of Cyprus’ Partition among Greek Cypriots: Political Economy and Political Culture in a Divided Society, Cham: Palgrave Macmillan, 2020, 79 (Greek edition)

[7] Id, p.79

[8] A referendum on the Annan Plan (the UN Secretary General’s plan for a solution to the Cyprus problem) was held in the Republic of Cyprus and the non-recognized Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus on 24 April 2004. The two communities were asked whether they approved of the fifth revision of the United Nations proposal for reuniting the island, which had been divided since 1974. While it was approved by 65% of Turkish Cypriots, it was rejected by 76% of Greek Cypriots. Turnout for the referendum was high at 89% among Greek Cypriots and 87% among Turkish Cypriots

[9] Copeaux E. &. Mauss-Copeaux, C., “Dividing Past and Present, The Green Line in Cyprus 1974-2003”, in State Frontiers: Borders & Boundaries in the Middle East, Edited by Inga Brandell, London & New York: IB Tauris, 2006

[10] Ioannou G., The Normalisation of Cyprus’ Partition, 101

[11] Bryant R., The Past in Pieces: Belonging in the new Cyprus, Philadelphia & Oxford: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2010, 1

[12] Ioannou G., The Normalisation of Cyprus’ Partition, 103

[13] Demetriou O., “To cross or not to cross? Subjectivisation and the absent state in Cyprus”, Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute 13 (2007), 987-1006

[14] Equipment used by engineers to measure altitude and distance.

[15] The reform school of Lapithos, was a boarding school for male juvenile offenders and an orphanage

[16] Ioannou G., The Normalisation of Cyprus’ Partition, 193

[17] Leonard M., “Us and them: Young people’s constructions of national identity in Cyprus”, Childhood Journal 19 (4), 2011, p. 467-480

[18] Christou M. & Spyrou, S., “What is a border? Greek Cypriot and Turkish Cypriot children’s understanding of a contested territorial division”, in Children and borders. Studies in childhood and youth, Edited by Christou M. & Spyrou S., London, Palgrave Macmillan, 2014.

[19] Ioannou G., The Normalisation of Cyprus’ Partition, 193

[20] This monument, is set in the house of Dr Ilhan in northern Nicosia, where his family was murdered during intercommunal attacks in 1963.

[21] Pyla is a village in the southeast of the island, the sole in Cyprus to have retained its mixed population after 1974. Before 2003, the minimal contact between Turkish- and Greek Cypriots would usually take place there or abroad.

[22] This literally translates as deli/bodega, but in Greek Cypriot dialect it refers to a roofed bazaar with small stalls, where one could find clothes, spices, jewelry, common in cities that lived under ottoman rule (ott. Bezesten).

[23] Maria later found out that he was making reeds for zurnas (traditional instrument)

[24] Christou M. & Spyrou, S., “Border encounters: How children navigate space and otherness in an ethnically divided society”, Childhood Journal 19 (3), 2012, p. 302-316

[25] This was the norm in cities that lived through Ottoman occupation (a division based on the millet system)

[26] Peristianis & Mavris, The “Green Line” of Cyprus, 165.

[27] Id, 166

[28] Leonard M., “Us and them: Young people’s constructions of national identity in Cyprus”, 478

[29] Heraclides, A. “Foreword”, in Ioannou, The Normalisation of Cyprus’ Partition.