Author and Researcher: Rez Latif

Instructed by: Dr. Barin Kayaoglu & Dr. Leslie Carr-Riegel

Transcribed into Kurdish by: Raz Latif

Abstract:

After her family decided to cross the boundaries and leave to their newly established country, Israel, teenage Nahida chose to stay behind and continue living among the people she grew up with. Nahida was a daughter of one of the several Jewish families in Chamchamal before the 1950s. These families left Iraq amid the creation of the State of Israel and the tension of the first Arab-Israeli war. This research approaches the theme of crossing boundaries from a different angle, an angle that is about not crossing national, religious, and cultural boundaries. The importance of this research and similar research are primarily in preserving and keeping alive stories that otherwise will die out and become victims of time. It is also a source for future researchers that will work on issues related to the case of the Middle East and Non-Arab communities in the region such as Kurds, Iranians, Jews and many other minorities in the region. After the establishment of Israel in 1948, Jews from all over the world headed to their promised land in hopes of better lives than the previous decade in Europe–especially the nightmares of the Holocaust. However, it was not only the Jewish communities of Europe who traveled to the promised land but rather Jews from all over the world, including those living in the Middle East and Arab countries, which became more hostile to Jews due to the creation of Israel in the late 1940s.

In Iraq and specifically, a small town called Chamchamall in Sulaimani province, a few Jewish families decided to leave for Israel in 1948 due to the first Arab-Israeli war. One of those few families was Abdullah the Jew’s family who had a dried products store in Chamchamall and was living with his two kids and wife. Haji Nahida, who is the main character of this research, was Abdullah the Jew’s (عبدلله جولەکە) daughter that chose to stay behind and convert to Islam rather than leave for Israel.

Nahida’s story is only one of the many interesting and historically important stories of the region that is related to the Jewish communities of Iraq. While this might be one of the first attempts to preserve that history, especially in English, this research aims to plant a seed of hope that more researchers and academics will achieve the motivation to work on other similar stories. Thus, this research will be dedicated for all the yet to be rediscovered Nahidas out there.

Introduction:

Before exploring the depth of Haji Nahida’s story, it is important to introduce the research first. The idea of this research started with some stories about an older Jewish woman that lived in the small community of Chamchamall in the 1970s. Thus, the original hypothesis merely extended into the simple statement of a Jewish elder in a majority Muslim small town in Sulaimani, Iraq, and the research question was a mere inquiry on what her story was. After some extensive research and blowing the dust off some dying stories held by older folks whose bodies are on the edge of life, yet their memories and nostalgia still reflecting past wisdom to the present, some of the stories about Haji Nahida proved to be a myth.

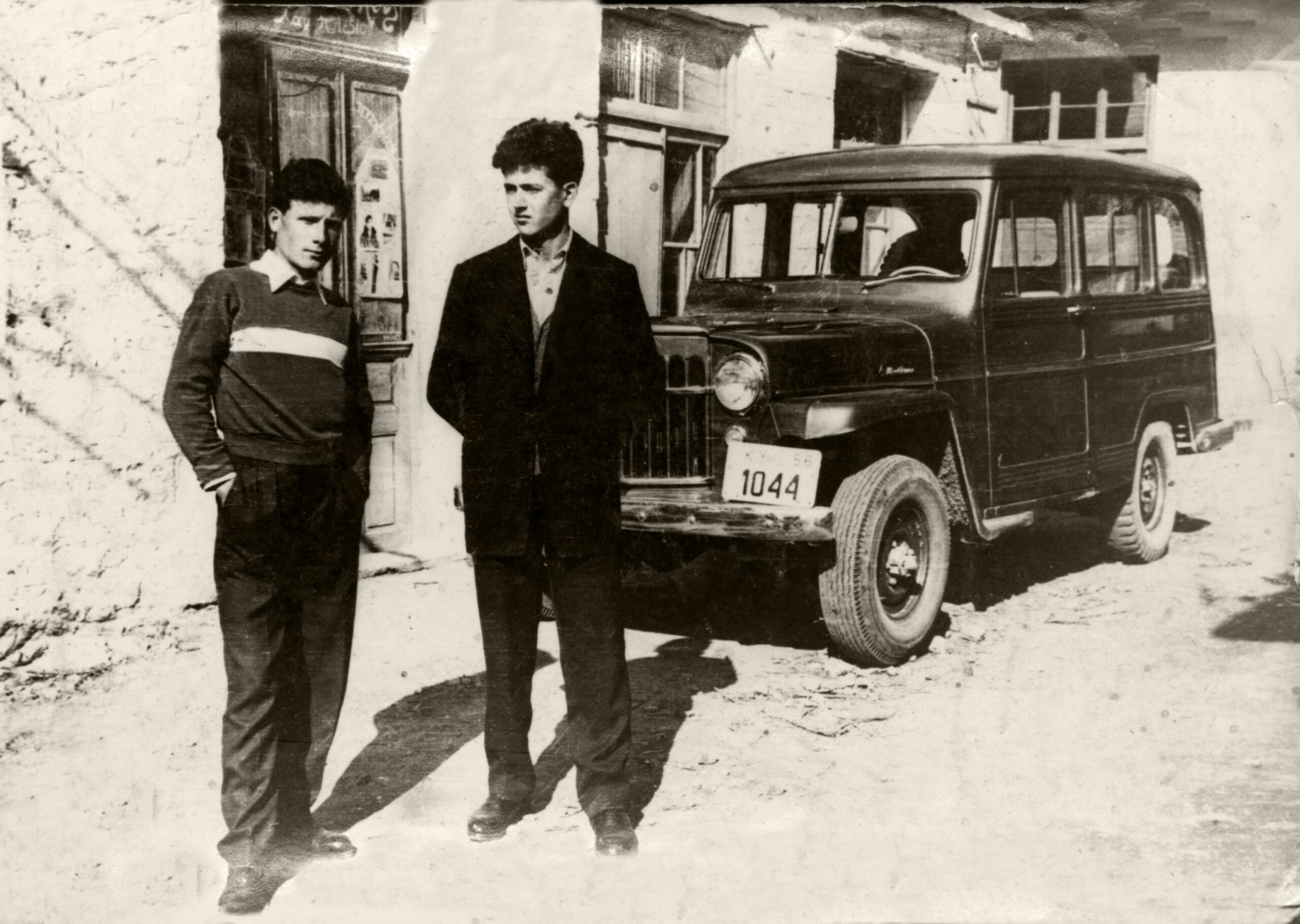

As with every research, however, there is no failure but only attempts that prove another possibility. Thus, exploring and researching the unreal stories about Haji Nahida helped in discovering her true story. Eventually, three people with knowledge of the subject helped to shape the story. I first heard the story of a female Jew who lived in Chamchamall from my father, Latif Fatih (53), who is a writer and is planning to include Haji Nahida as a fictional character in his next novel. Then, my second contact and first interviewee was “Kak Arif” (78)who is an octogenarian friend of the family, and still remembers some of those days where Chamchamall was still a multi-faith community. Kak Arif then sent me to “Mamosta Sabir” (82), who is a writer and a well-known figure in the town due to his educational contributions and his writings towards preserving the history of the town.

After conducting several interviews with Mamosta Sabir and reading his autobiography, Haji Nahida’s story was ready. The story took place in Chamchamall, which is a small town in Sulaimani in the Kurdistan region of Iraq, about the story of the Jewish families that used to live in the area before the creation of Israel, as well as the story of a daughter of one of those families who stayed behind and because she wanted to live among the people she grew up with.

Background: Jews of the Middle East:

The State of Israel was created in 1948. In the 1922’s Mandate of Palestine, the League of Nations recognized the connection of Jews to the land of Palestine and creation of a Jewish state where the rights of Jews and Muslims would be protected while also recognizing the rights of the Palestinians. This was supposed to be a shared land between Christians, Jews and Muslim-Arab Palestinians that were already living there (Mandate for Palestine, 1922). The story Jews in the Middle East goes back to when the prophet Moses and his people settled on the land of modern Israel and Palestine, and then Babylonian and later Roman invasions scattered them all over Europe, the Middle East, and Africa. Following the spread of Christianity and Islam in the region, the Jews of the area became a small minority. In general, the Jewish community of the Middle East, Arabic parts of Africa, and central Asia were and are known as Mizrahi Jews. Before the creation of Iraq in 1921, the Jewish communities of the area, who had lived in the region for hundreds of years, were known as Mizrahi Jews. However, after the League of Nations’ decision in 1922, the Arab majority areas of the Middle East became more hostile towards these Jewish communities. However, it was mostly after 1948 and the first Arab-Israeli war that the majority of the Jews of the Middle East left most of their lives behind and traveled to Israel. In Baghdad, the capital of Iraq, where one of the biggest Jewish neighborhoods of the region was located, only a few families were left once the dust settled. Dar Al-Yahud, the house of Jews, is one of those examples that are spoken of in detail at the Museum of the Jewish People (Museum of the Jewish People).

Jewish Families of Chamchamall:

In the small community of Chamchamall, there were three Jewish families. Mira, who appears to have been wealthier compared to the others, would stay only a few days a month in Chamchamall, while his family lived in the nearby city of Kirkuk. There was Isaac, whose wife had passed away and was living alone. He was a Khoomchi. Khoomchies were people who dyed cloth fabrics using Khoom which was material available in Red and Blue. Finally, there was “Abdullah the Jew” who had a dry products store in the bazaar, and his wife Lulu sold liquor at home. Abdullah and Lulu had a son named Naj and a daughter named Nahida.

Mamosta Sabir says that the Jewish families were very cautious with what they ate–Specifically, they did not eat the food of the Muslims since they had the belief that the Muslims were not clean enough to qualify as “kosher”. Mamosta Sabir recalls that this was common among Jewish folks in Chamcahamal and nearby areas. For example, Muslims had no qualms about cooking the meat and vegetables in the same pot, but Jews preferred to have the pot for meat different from the pot for vegetables. When they were buying a new pot, they were washing it with mud and doing regular washing with water too. They also did not eat the meat from the animals slaughtered by the Muslims. They had the tradition of having one of them who was an expert in animals, called Malum. Their Malum(مالوم) determined whether the animal was Terefah (تاریف) or Kosher (کاشیر). Mamosta Sabir also states that he once asked Mira what was Terefah and what was Kosher, and Mira told him that Terefah was when the animal was sick and had its lungs and tissues stick to its ribs, and Kosher was when the animal was healthy and its lungs and tissues did not stick to its ribs. This part is important and relevant to Haji Nahida since this culture affected her and helped her later on in life to be known as a clean and reliable maid.

Chamchamal Jews were also famous for their trading and business skills. It is said that when they were selling sugar, they were not putting any profit on it, while the Muslims were putting a few dinars profit on each kilogram. For example, if a kilogram of sugar were to be sold at the market for 50 dinars, the Muslims would sell it back for 54 dinars while the Jews would sell it back for 50 dinars. However, the Jews were making a profit off of the sacks and ropes that were left behind from the sugar sacks. They were also going over the villages in winter and were asking the shepherds to sell them their wool in spring in return for paying in advance. This later on reflects in Haji Nahidas life as she works for her own money, even after she is married and converted to to Islam, considering that in Islam the wofe is not required to work while the husband is required to work and meet the financial needs of the whole family.

As for their religious ceremonies, Chamchamal Jews had no shrines or temples in Chamchamall, but they had temples in Sulaimani and Kirkuk. However, I could not find traces of their places in Kirkuk, mostly because after asking around, very few people remember them. Mamosta Sabir even mentions the area where they used to be in Kirkuk, and it was still hard to find and mark their places. Kirkuk and Sulaimani have changed drastically since the fall of Saddam Hussain’s regime in 2003. The only old places that can be easily marked are those that their owners have preserved, and there are not enough Jews left in both cities to preserve their temples, as the continuous and progressive antisemitism acts of the Ba’ath regime forced the majority of them to flee.

The Jewish families and the Muslims were living peacefully together in Chamchamall, yet, eventually, in 1948, those families left in a rush as the first bullets of the first Arab-Israeli war were being fired, and the Iraqi government was also pressuring them to leave. Nahida stayed behind and became a Muslim, while her family left in a hurry. Isaac and Abdullah sold their belongings for a cheap price, while Mira could not manage to sell his herd of a few hundred sheep and left them behind, which later the Iraqi government took over and sold to people. As for the economy of Iraq after the Jews, Mamosta Sabir says the Faili Kurds, who are a diverse ethnic group of Kurds that used to live primarily in Baghdad, took over, but with the Ba’ath party taking power in1968, especially later on under the leadership of Saddam Husain from 1979 to 2003, the Faili Kurds were heavily targeted. With the departure of Jews, Faili Kurd merchants from Iraq-Iran borders started to settle and replace Jews, and the knowledge Faili Kurds had about Iraq-Iran borders and trade routes made them good candidates to take over the Iraqi economy and replace the Jews (Minority Rights Group International).

Haji Nahida:

When her family left, Haji Nahida, who was around the same age as Mamosta Sabir, was ten or twelve years old. She stayed with Hama Xhurshi and his wife Sakin, who were friends of her Family and also relatives of Mamosta Sabir, until she matured. As Mamosta Sabir recalls, Nahida stayed behind because she had no incentive for Israel as a state that was all new to her while she had lived her life with the Muslims of Chamchamall and was growing up with them. Mamosta Sabir said that Nahida told her parents that she wanted to stay with the people she knew and she grew up with, and be on their belief, rather than to leave to an unknown place. For Nahida, she already had an identity among the Muslims and people of Chamchamall, But Israel was new to her, and to live in Israel would have meant to rebuild that identity. Then, she left for Kirkuk and worked as a home cleaner and a maid for others, and she stayed with a cousin of Mamosta Sabir’s mother named Said Mustafa and his wife Fat’hia. She was given a room there. She was famous for being good and clean at her job. During that time, she went on a Haj pilgrimage to Mecca and thus came to be known as Haji Nahida from then on. She went to Baghdad and worked in Doctor Zanun’s, who is another figure around Chamchamall and Kirkuk that is currently living in the United States and is also a friend of Mamosta Sabir, parents’ house. Then she came back, and when she was around her forties, she married a relative of Mamosta Sabir named Hama Nuri. Mamosta Sabir says that Haji Nahida was a good person but she was very outdoorsy. She was not the type to stay home. Thus, she got divorced from Hama Nuri only three months into their marriage. Hama Nuri later told Mamosta Sabir that their only problem was that he was an office worker and every afternoon when was back home, Haji Nahida was giving him dinner and after-meal tea and was asking him to go out to be with his friends while she would go to hers. Since Hama Nuri was tired after a long day of work every day, he was not willing to leave the house. Hama Nuri’s desire to stay at home conflicted with Haji Nahida’s desire to be outdoors created a situation where Hama Nuri decided to end the marriage. Haji Nahida only lived a few more years after that. She died in the early 1980s leaving no one and nothing behind.

Conclusion:

While Haji Nahida’s life is nothing extraordinary compared to some of the stories that make it to best-selling books and even Hollywood and her story is fairly short, there are two parts of her life that draw attention to her: first is her decision to stay behind and not leave with her family, and second is her lonely death. It would never be known how Haji Nahida’s story would have turned out had she left with her family. Interestingly, not much is known about what happened to her brother and parents. It would be like searching for a specific fish in a river that keeps moving, but yet even though most of the people who knew Haji Nahida are either in heaven or are waiting to be taken there at the edge of their seat, yet as if she is making up for her lonely death, her story clings to life while many of her era and time are but bones. It is the hope of this short research to draw a path that will be taken by other researchers and help Kurdish, Jewish and Arab historians to work on many other stories like this of Haji Nahida and preserve that history of the region.

Glossary:

- Haji is an Arabic-Kurdish prefix that is given to anyone who has done the Haj pilgrimage in Islam.

- Kak is a mostly formal Kurdish prefix that reflects respect for anyone older, even if the age gap is less than a year.

- Mamosta is the Kurdish word for teacher. However, it can be given to anyone with some extensive knowledge in a field. It also adds the element of respect to its possessor.

- Said is a religious Arabic term for those who are claimed to be descendants of the Prophet Mohamad.

- Terefah is a food that is forbidden or not good to be eaten based on Jewish traditions.

- Kosher is a food that is good to be eaten based on Jewish traditions.

- Malum might have been taken from the Hebrew word Ma’lum that in some contexts means “from above”, and thus, describing people with more power such as Rabbis.

Credits and Citation:

Other than the three interviewees with Mamosta Sabir, his autobiography is also used in this research mainly to confirm Mamosta Sabir’s memory that old age is now staring at. Kak Afrif and my father, Latif Fatih, have not had much of their words included mainly because Mamosta Sabir’s words and interviews were more detailed and inclusive versions of theirs. However, it is their guidance that helped the research to reach the point it is at now. Finally, my sister, Raz Latif, transcribed the interviews in Kurdish, and without her, it would have been a shameful experience to put my terrible Kurdish writing skills.

Secondary Sources:

- Minority Rights Group International. “Faili Kurds”. Minority Rights Group International. 2017. <https://minorityrights.org/about-us/>

- Museum of the Jewish People. “The Jewish Community of Baghdad, Iraq”. Museum of the Jewish People. <https://www.anumuseum.org.il/jewish-community-baghdad-iraq/>

- League of Nations. “Mandate for Palestine”. League of Nations. 1922. <https://content.ecf.org.il/files/M00301%20-%20Text%20of%20the%20British%20Mandate%20for%20Palestine%20(1922).pdf>

- Ali, Sabir. “My Life’s Memories (بیرەوەریەکانی ژیانم)”.