Introduction

Background information

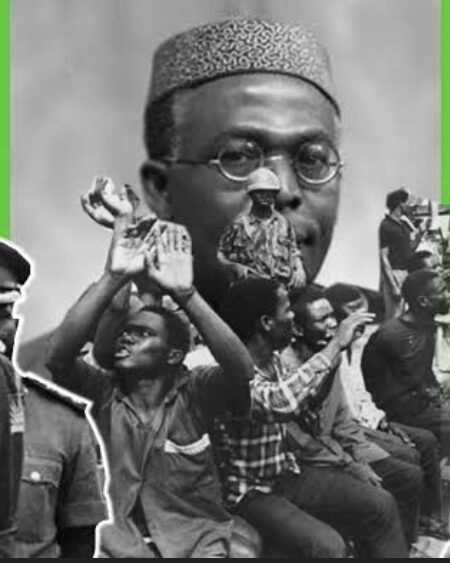

In the 19th century, India, Bangladesh, and Pakistan were united under British rule. On 15 August 1947, the former British territories were partitioned into two independent states: India, and Pakistan. Pakistan was divided into two a majority Bengali speaking East Pakistan and majority Urdu speaking province of West Pakistan, separated from each other by a vast stretch of Northern India. A growing political rift between the two provinces, mainly on the language question, intensified in 1971. In this context, the people of East Pakistan started the struggle for independence which was finally achieved in 1971. At first this struggle began in urban areas of East Pakistan but later spread to the countryside. After the speech of East Pakistan’s political leader Sheikh Mujibur Rahman on 7th March, the rural people of Bangladesh participated in the jatio-andolon (national movement) against the Pakistani Bahini (Chowdhury 1).

Growing up in Bangladesh, I had heard and read many stories about the Liberation War. Some of these stories emphasized the role of political leaders in the Liberation War of 1971, others talked about the contribution of ordinary people, and still, others brought to light horrific stories of sexual violence that shaped the experience of the War. In all these existing narratives, I never learned about the experiences of ordinary rural women during the political movement. My curiosity about the contribution of rural women during the War first led me to this research project. My research is based on interviews with women[1] in Neyamotpur and Kajla village whose were not only witnesses of the 1971 War, but also participated in the War in their own unique ways.

My essay tells the history of the War from a new vantage point, shifting the lens from urban areas to rural areas, from men to women, and from the major battlefields of the War to stories of everyday lives. This essay explores factors that challenged rural women’s abilities to procure food for their households during and after the War. In the next section, I situate my analysis of the changes brought about by the War against an account of the division of labor in rural Bangladesh before the start of the War. Thus, this essay puts forth an inter-sectional analysis of gender roles and socioeconomic status of rural women in a patriarchal society like Bangladesh.

Gender roles, the impact of War, and the influence of socioeconomic status

Gender roles are constructed on the basis of the values, beliefs and views of a particular community, group and society which are expected to fulfill by different sex (Blackstone 335). The gender roles of rural Bangladeshi women are shaped by traditional gender norms that govern how daily activities, socioeconomic status, and religious views structure Bangladeshi rural society. It is important to emphasize that socioeconomic status and gender function in tandem in this society. That is socioeconomic status shapes gender roles within the society. Conversely, due to the economic crisis before the War and the political movement during 1971, significant changes occurred in the socioeconomic status of rural people which influence the gender roles of rural women.

Division of work in rural area

During 19th century, elite Bengali Muslim women were expected not to go outside and do household activities within the home. Despite this, before the War and during the War, women of all backgrounds had a significant role in an agrarian society. Statistics of rural labor were divided into two segments: household work and farm work. Household work included activities such as cooking, childcare, cleaning, grinding spices, and preparing food among others which were all typically performed by women (Westergaard 13). By contrast, farm work was mostly performed by men although with significant involvement of women as well. Men were engaged with food production by doing the bulk of the farm work. Men-dominated activities were plowing, sowing plants, irrigation, harvesting, collecting, and threshing (Women in Bangladesh 25). On the other hand, women also participated in farming, but there were differences in work types. Women-dominated activities were husking, grinding spices, preserving, and processing of crops (Women in Bangladesh 25).

Despite playing these important roles, women’s work was considered “unproductive” as their work was unwaged and done within home (Holmstrom 189). Those activities were encapsulated in gender norms that rural women should do in rural society in their roles as mothers, and daughters-in-law. Besides these farming activities, rural women in Bangladesh—who were predominantly Muslim—also undertake most of the housework. In this work, their activities were governed by gendered codes of appropriate behavior,

The powerful ideological operator in Bangladesh is very much related to the Muslim religion. The religious norms as regards women prescribe that women observe purdha, i,e. that they should not be seen by males outside the family (Westergaard 10).

Thus, in the peasant group of Bangladesh, there was an influence of Muslim religious norms. Therefore, the prestige issue of peasant culture was related to the ritual of purdha. As a result, most of the rural women did their household activities and farming “inside the bari” (inside the home) (Westergaard12). Moreover, household activities and unproductive farming work were also divided into two categories: bhitarer kaaj (inside work) and bahirer kaaj (outside work) based on the socioeconomic status of a rural family (Westergaard 12). Those women who belonged to a more elite socioeconomic stratum more readily adhered to the purdha system and employed non-kin women to do their bahirer kaaj (Westergaard 12). Hired female labor was used to help with grinding spices, husking, and the cleaning of vessels and yards (Westergaard 12). On the other hand, bhitarer kaaj, such as taking care of children and cooking, was done by those who belonged to a more elite socioeconomic stratum.

One of my interviewees, Komli Chowdhury, came from a family of means, with 20 acres of land to their name. During 19th century, 20 acres was considered a huge amount of land in rural areas which granted landowners an elite status. Given their elite social status, they were stricter in observing social and religious norms. She said that she did not go outside the house for any work, “I did cooking, cleaning before the 1971 War. Even while I visited my parent’s house I had worn burkha (black veil) for purdha” (Chowdhury). During the War, the military burned Komli Chowdhury’s in-law’s house. Even during the War and in economic crisis, women were often not allowed to come out of their traditional gender roles. In describing her daily activities during the War, the relatively elite Komli Chowdhury said:

During the war, my husband was not at home for some months as military forces killed most of the young people. In the absence of my husband, my father-in-law takes care of us. My daily activity remained the same as before the War. I did not go outside for any work: I did cooking and served food to my family members and bahirer kaaj was done by my female helping hand. (Chowdhury)

Therefore, for those rural women who inhabited an elite socioeconomic status, their form of labor had not changed very much. Thus, the roles of women in the rural economy were not just determined by gender norms but also by socioeconomic status. Elite women’s mobility was restricted to the household. Therefore, their labor was mostly performed within the household. Elite women’s status, as well as involvement in the labor force, remained more or less the same through the War.

Transformation of status: from elite women to working women

By contrast, during 19th century, socio-religious norms that were given by the society were not always strictly followed by poor and landless rural women. Though they were strictly bound by socio-religious norms, their crisis motivated them to take greater part in bahirer kaaj both before the War and during the War. Another interviewee Milona Akhtar had three children before the War. Her husband inherited approximately three-acres of land which he worked on himself. She undertook all household activities by herself. In describing her daily housework before the War, she said, “I did cooking, cleaning, taking care of children, grinding spices and drying crops. But I was not allowed to go outside to work” (Akhtar). Given the gendered norms restricting women’s movements outside the home, Akhtar rarely stepped out of her home before the War. Most of her time was spent conducting household activities and some kinds of farming activities that could be performed inside the bari (home).

However, during the War, her family experienced food shortages. She described the War years as follows, “There was no time to do the farming activity as people were always afraid of military force. We always remained prepared to escape and run” (Akhtar). This meant that her family did not get enough time to cook and eat food. She added, “we mostly ate atar jau (soup of wheat)” (Akhtar). However, during the War, her family was not able to harvest their paddies from their fields as there was heavy rain and people were afraid to go to their paddies out of attack by the military. Thus, villagers lacked access to rice, a staple food item. Therefore, they were not able to sell their crops to earn money to purchase food for household consumption. So, they mixed rice with potato and cooked khichuri (curry that is made with rice and vegetable) as their main meal.

Accessibility of food during War

There were some distinct changes in the accessibility of food compared to before and during the War. The price of some essential grocery items increased rapidly due to the economic crisis of the War. For instance, the price of one kilogram of salt was two taka per kilogram before the War and during the War it became twenty to eighty taka per kilogram (Chowdhury 37). As salt is an essential item for cooking curry, purchasing salt posed significant difficulties for people. Moreover, the main meal of rural people was rice. During the War, rice became twenty two taka per kilogram from ten taka per kilogram (Akhtar). Thus, the dire consequences of the War pushed my interviewee, Akhtar to ignore the restrictions of purdha and seek work outside the house even though she was pregnant. This point was corroborated by Custers whose work argues that during the economic crisis Bangladeshi rural women were forced to look for work outside the house by ignoring purdha rules so that they could ensure their own and their family’s survival (213).

Though it was Wartime, Akhtar was able to employ herself. She worked in the home of an elite rural woman as a house servant. She said that, “in my working place, I have done grinding spices, cleaning of yards and vessels. I had not done any work that men did like planting, collecting, or husking crops” (Akhtar). Moreover, while she worked in other people’s houses, she continued to perform her own household activities. To explain her daily activities during the War, she said that “During the War, I have done both my barir kaaj and bahirer kaaj” (Akhtar). She did not join an industry or some other economic institution as a worker. Her experienced also shows that in a patriarchal society, even when women work outside the home, they continued to do domestic work in their own household also. Yet, by stepping out of the house, Akhtar discarded the restricted purdha system and did not abide by strict gender norms pertaining to rural women. Thus, she was breaking the stereotypes of gender roles as maintaining strict purdha was more or less mandatory for a Muslim woman at that time.

Status of rural women’s work

Similarly, doing household work within the house and doing household work outside the house were two different things. For one, household work was not considered productive work: it was not valued as work in a society structured around market value. Rather, it was considered to be natural and even mandatory that women should perform all labor inside the home. However, within women’s own home her household work considered as unpaid while the same kinds of household work she did outside the home in other people’s houses became paid work. There was thus a distinct difference in term of valuing the household work. On the flipside, while women’s work outside the home became paid work, and hence “productive” according to social norms, it continued to be devalued in the society because women had broken purdha norms.

To demonstrate the restrictiveness of the purdha system in 19th centuries, Bengali feminist thinker Begum Rokeya in her book Abarodh Basini (The Secluded women), held that the purdha system was so strict that she was not even allowed to be seen unveiled in front of the female home servant in the house who came from the home of one of her own relatives (14-15). Her statement had shed light that during that time, the purdha system was so strict that those women who worked outside the home were regarded as equals to men as they also go outside without maintaining purdha like men did and for this reason elite women were not allowed to go in front such women. Moreover, her statement explicitly demonstrated that those women who work outside were also devalued according to these norms.

Therefore, the elite women who stepped outside of the home due to the crisis also faced social opprobrium for non-conformance of traditional gender roles. In this regard, my interviewee said that “working outside did not look good to the society but for the survival of my family I had to work outside” (Akhtar). Thus, in both situations, women’s work is devalued within the home and outside the home. These experiences show the inter-sectional relatedness between gender norms and socioeconomic status.

Life of rural landless working women

Before the War, some rural women were already engaged in waged work outside the home as they were landless or in economic crisis. Their socioeconomic status was low compared to other families in rural areas, as they did not inherit any land for cultivation. Therefore, rural women were also employed in outside work before the War by breaking the purdha rule. One of my interviewees, Amina Khatun was an uneducated, landless poor woman. Her husband inherited a home which was made by dried straw of jute and they hand no land to cultivate. From her perspective, surviving was more important than maintaining the norms of purdha as her husband’s earnings were not enough for her family to survive (Khatun). She was employed by a rich family where she worked as a housemaid. In describing her daily activities before the War, she said, I woke up early in the morning and started cooking and cleaning. After that, I went to my workplace where I did grinding spices, cleaning vessels, and helping the wife of the owner while she cooked (Khatun). So, in her workplace, she mainly did the bahirer kaaj and, in her home, she did both types of work. Similarly, during the War, she continued her work, though she did share the following:

During the War, we were not able to manage our daily meals as there was a crisis at work and most of the time my family members remained hungry. Sometimes I blended “khei” (water lily seeds) and made cake with that. Due to hunger, one of my daughters died during War. (Khatun)

For her, every day was like War as her economic condition was not good. When she was young, she was able to work outside, but today she is an old widow. Her children do not look after her. Therefore, she has started to beg for her livelihood. Her example suggests that working women were routinely employed in the agrarian labor force before and during the War. This division of labor continued to structure women’s work during the War as well. Women in this demographic did not conform to the norms of the purdha system out of economic necessity and had to find ways to reconcile this necessity with their religious identities and obligations as Muslims. This example reinforces my arguments that definitions of gender role were dependent upon socioeconomic status.

The absence of support from male members of the household in a patriarchal society

In a patriarchal society, women’s economic condition depended on men’s socioeconomic status. One of my interviewees, a rural woman named Alali Begum was married at an early age. She came from a family of means, which owned seven acres of land. Those lands were enough for her family members to survive. In addition to their land, she and her husband had a home which made of jute straw. Before the 1971 War, she was newly married and did not have many responsibilities in the household. Her mother-in-law did all the activities, and she was always busy playing. But there was change in her life during the War. While describing her life during the War, she said “I began to take a more active part in household work during the War. I started cooking and cleaning as my mother-in-law was busy working outside” (Begum). Therefore, the War brought distinct change in her daily activities as the situation had changed. She recounted her experiences of the War as such:

We did not have enough time to cook and eat as we knew that military forces could anytime. When we heard military forces, we used to hide on the small hill tracts of our area. Therefore, when we had time, we used to prepare and store some pitha (dry cake) to eat while hiding in hill tracts. (Begum)

After the War ended, she gave birth to a child. A few years after her child’s birth, her husband died leaving her a widow. While her husband was alive, she did not have financial problems as her husband took financial responsibility for their household. But after the death of her husband, she did not inherit any assets or land from her husband as her husband had passed away before her father-in-law. Other men from her in-law’s house forcefully took control of all the property that was her due. Moreover, as her son was also younger at that time, he also did not inherit land from her father-in-law as “living law” was more significant than “lawyer’s law”:

The village community’s autonomy is reflected in the decisions taken at the grassroots level by village elders or matbars/mondols at the informal village court (salish), flouting the law of the land and the Sharia. Administering the Bengali rule of inheritance is simply a village affair. Thus, in accordance with the ‘Bengali system’, which reproduces a gender hierarchy quite different from the teachings of Islam, Muslim women may be disinherited. The subjection of women in the region is done in accordance with the Bengali concept of ‘masculinity’, there is nothing Islamic about it. (Hashmi 7)

Here, according to religious law, she was meant to inherit land, but, due to the village court law she did not get ownership of any land. As a result, she and her son were forced to go back to her parent’s house. Similarly, she did not inherit any land from her parents also as they were landless. Upon her parent’s insistence, she got married again. So, in Begum’s life, another man stepped in to support her and provide for her survival. Her second husband also had approximately two acres of land which was not enough for survival. For the family to survive, she needed to supplement her household income through her own earnings. She therefore decided to work outside the house and started work as a house maid. She said that, “I worked in other people’s houses where I cleaned vessels, yards and cooked” (Begum).

Then, after some years, her second husband also died and left her with a small proportion of the inheritance. In her second marriage as she did not have any children, most of the land was inherited by relatives of her husband. To support herself, she said, “till now I work in other people’s houses as a maid for my livelihood” (Begum). Therefore, in a patriarchal society, the absence of support from male members of the household forces landless women like Alali Begum become helpless and seek low-paying jobs like household work to support themselves.

The Bangladeshi War researcher Afsan Chowdhury corroborates this argument while writing about a rural woman named Rohimon Beua whose son and husband were killed by the Pakistani military bahini. As there was no male member in her family, people forcefully took all of her land. There was no one to look after her as her daughter also got married. Therefore, she said that “now I spent my livelihood by begging” (Chowdhury 81). Thus, in a patriarchal society, a poor widow became helpless without the support of a male member and their way of livelihood depended on the gender norms of a society.

Life of elite rural women in the absence of husband

In terms of elite women gender roles can be different from the landless working women. During the war, men joined in the War and their wives were at home, but they were usually accompanied by another male member of the household. One of my interviewees was the wife of a freedom fighter name Korimon Banu. She inhabited an elite social status as her family inherited 30 acres of land. She lived in a proper brick house. Before the War, she only took care of her family and cooked for her family members. While describing her daily life before the war, she said, “I just need to take care of my newborn child and my housemaid did other works” (Banu). By the time her husband joined the War, her child had grown up by a few years up. Speaking of her work during the War, she said:

My father-in-law did all the work outside and took responsibility for decision-making. I have not done any new work like decision-making or working outside. My everyday work during the War was taking care of my children and cooking for my family members. (Banu)

Moreover, they did not face any financial crisis as her family had a large landholding along with a small business. In Banu’s case, in her husband’s absence during the war other male family members stepped into play his role:

Men think that women should not participate in decision making in ‘off-bari’ (outside home) matters either. Most rural women – 90 to 97 per cent (depending on their economic background) – do not regard themselves as equal to men in respect of ‘off-bari’ activities. (Hashmi177)

Moreover, socioeconomic status played a substantial role in the malleability of gender roles among rural women in Bangladesh. Therefore, the gender norms of Bangladesh’ patriarchal society did not allow women to make any decisions as men almost always replaced other men in women’s lives. The absence of male authority rendered women’s conditions and livelihood even more vulnerable.

Conclusion

To sum up, for rural women, the challenges to maintaining their livelihoods during and after the Bangladeshi Liberation War were crucially related to issues of food accessibility. Transformations in gender roles did not only depend on the material effects of a given political movement but also depend on economic strain it produced in the socioeconomic status of rural women. Changes in socioeconomic status affected the changes in gender roles of rural women. For most of the elite women, War did not bring up any changes in their gender roles as their families had means to support the households. On the contrary, for landless and poor women, there was distinct change in gender roles that stemmed from economic necessity. In the face of economic crisis, many women sought waged work outside the home. Despite this change, women’s work outside the household continued to be devalued because it was considered a violation of religious and cultural norms for women. Thus, my paper shows a) the intersections of gender and class in shaping women’s lives and b) the possibilities as well as limits of changes in women’s lives as a result of major sociopolitical movements.

Works Cited (MLA 8th edition)

Secondary Sources

Chowdhury, Afsan. Narider Ekattor. University Press Limited, 2022.

Chowdhury, Afsan. Gramer Ekattor. University Press Limited, 2019.

Hashmi, Taj. Women and Islam in Bangladesh. Macmillan Press Ltd, 2000.

Rokeya, Begum. Abarodh Basini. Create Space Independent Publishing Platform, 2018.

Holmstrom, Nancy. “”Women’s Work,” the Family and Capitalism.” Guilford Press, Vol. 45, No. 2, 1981.

Blackstone, Amy. “Gender Roles and Society.” Human Ecology: An Encyclopedia of Children

,Families, Communities, and Environments, edited by Julia R. Miller, Richard M. Lerner, and Lawrence B. Schiamberg. Santa Barbara, 2003.

Westergaard, Kirsten. Pauperization and Rural Women in Bangladesh. Samabaya Press, 1983.

Women in Bangladesh. “National Report to the Fourth World Conference on Women Beijing

1995”, 1995.

Primary sources

Chowdhury, Komli. Personal interview. 21 May 2022.

Milona Akhtar. Personal interview. 21 May 2022.

Amina Khatun. Personal interview. 22 May 2022.

Korimon Banu. Personal interview. 21 May 2022.

Alali Begum. Personal interview. 22 May 2022.

[1]Women’s pseudonym has been used to preserve the privacy.