Kurds are the largest ethnic group in the world without a country. 1 Since 1918, they have been divided between Iraq, Iran, Turkey, Syria, and the Soviet Union. In my research, I am concentrating on the Kurds in the northern part of Iraq. After being under the British colonial rule, the conflict of Iran-Iraq war, and many uprisings under Sadam’s rule, they were given an autonomous region, called Kurdistan. Due to the reason that Kurds were involved in frequent wars and conflict, they have lost the majority of their archives several times. All that exists now is what could survive outside of Kurdish land.

Throughout history the people who dictated the narrative of how Kurdish memory is formulated about the past were outsiders, colonial administrators, early travelers, and most recently, Western journalists and photojournalists. Susan Meiselas, in her photographic historical book about the Kurds, Kurdistan In the Shadow of History, writes about the photographs that the Western historians and travelers have about Kurdistan and says: “We have the object, but it exists separated from the narrative of its making.” 2 Kurds were able to portray themselves only through the work of outsiders and their subjective perspectives. Going back to our history, we mostly have seen ourselves in the narration of others rather than our own, which is dangerous because Western narrations are full of personal opinions and biased judgments, and concentrate only on a small quarter of the Kurdish community.

After the formation of the Kurdistan autonomous region there has been a slow emergence of local photojournalists. They are a new generation whose narration challenges the narration of foreigners before them, and are changing the perspectives of Kurdish and Western communities by portraying Kurdistan and the life of the Kurds. Now, these local photojournalists are the representative sources for broadcasting the news and stories of their own country and people, in their own view, thus also creating sources for future generations

Although Kurdish photojournalists have not for too long taken part in narrating their own stories, they now play an active role in creating a more accurate, fleshed-out, and heartfelt portrait of Kurdish society that resonates better with the people represented. Due to these portraits, they are contributing in a crucial way to the process of forming Kurdish memory and identity for generations to come.

The Photojournalists I interviewed

I have always been interested in the process of documenting and archiving. When I was in college, I found photojournalism to be an effective tool to document and archive. I was passionate to know more about it, but because we have few resources about photojournalism in Kurdistan, I was not able to understand the whole process. Now through my research I have gotten the chance to directly hear from the photojournalists, those who choose to document and those who are creating the images. Also, I have had the chance to learn more about the history of photojournalism in the views of the photojournalists. I have interviewed five Iraqi Kurdish photojournalists to investigate this topic more and understand the vision and ideas behind the photojournalists who create the photographs of Kurds and Iraqis now.

Ali Arkady, born in 1982, is a photojournalist and filmmaker from Khanaqin, Iraq. He graduated from Khanaqin’s Institute of Fine Arts. He started to work as a freelance photographer in 2006. Ali is now a member of VII Photo Agency. He has won the prestigious Bayeux Prize for War Correspondents. His works have appeared in CNN, The Telegraph, and The Times. 3

Hawre Khalid, born in 1987, is a photojournalist from Kirkuk, Iraq. He has a degree in journalism. Hawre started to work as a freelancer in 2007. His works have appeared in Times Magazine, New York Times, Washington Post and Sunday Times. 4

Sartep Osman, born in 1990, is a photojournalist from Sulaimani, Iraq. He has been working as a local photojournalist since 2009. Sartep won the Open Eye Award in 2011. He now works as a daily photographer in a local website in Sulaimani. His works have appeared in Time Lightbox, Universal News and Rudaw. 5

Younes Mohammad, born in 1968 in Dohuk, Iraq. He has worked as a freelance photojournalist since 2011. He received his MBA at the University of Tehran. He has received many awards, including from MIFA and DAYS JAPAN. Younes started late in his career but he is now a very well-established freelance photojournalist worldwide. 6

Sangar Akrayi, born in 1988, is a photojournalist from Erbil, Iraq. He first worked as a journalist and a street photographer and has now been working as a photojournalist for four years. Now Sangar works as a daily photojournalist for Middle East Images. 7

The Establishment of Photojournalism in Kurdistan and the Kurdish Photojournalists

The Kurdish people in 1991 rose against Saddam Hussein’s regime, leading to the establishment of an autonomous zone for the Kurds in Iraqi Kurdistan. This autonomy led to greater freedom within the Kurdish part of Iraq, and this freedom opened up the region toward visitors from foreign countries, construction, development in every sector, and trade with other countries. This was the first step of opening up toward the world and building connections with the media outside of Kurdistan; before this unprecedented freedom that Kurdistan experienced, the connection that local photographers and journalists had with outside media was limited. This lack of connection was put beautifully into words by Rafiq Mahmood Afandi, a Kurdish photographer from Sulaimani that inherited his studio from his father who owned one of the first photo studios in Sulaimani since 1946. “Each one of us [photographers] worked alone and kept our secrets to ourselves. Nobody was allowed to contact people here.” said Rafiq, who has since passed away, when he was interviewed about this topic by Susan Meiselas. “I didn’t meet any journalists or photographers. Maybe they came and were with the leaders but nobody came to me to exchange ideas about photography.” 8

Kurdistan’s freedom opened the way to establishing the first photo agency in Kurdistan, named Metrography. This was the start of shifting the narrative of the stories from the West and the outside world to the narration of local photojournalists, because before that “Iraq’s nuanced visual record wasn’t being made by Iraqis.” 9 This change was important because it has changed how the news of Kurdistan was delivered afterward.

Metrography was the first photojournalism agency in Iraq, founded in 2010 by Iraqi photographer Kamaran Najm and American photojournalist Sebastian Meyer. Metrography has gained worldwide recognition and the work of its photographers has been exhibited internationally and published on some of the most renowned media outlets around the world, Such as New York Times, National Geographic, Time Magazine and Washington Post. They define themselves in this way: “We specialize in in-depth photo storytelling from the best regional photographers.” 10 They say further: “We represent local photographers who give us unrivaled knowledge and access to every corner of the region.” 11

After Kamaran went missing in June 2014, while covering an encounter between the Peshmerga forces and ISIS fighters in an area around Kirkuk—his whereabouts are still unknown—his brother Ahmad Najm became the director of Metrography. Their works have slightly changed from the time that Kamaran and Sebastian were co-directing it, now it works more on setting up workshops and opening exhibitions in Iraq. Last year they brought The World Press Photo Special “Exhibition: Best of Three Years” to three cities of Iraq.

In 2011, the Metrography agency based in Sulaimani offered a ten-day photographic workshop by four renowned foreign photographers for 23 local emerging photographers from all the cities of Iraq. Ali and Sartep both participated in that workshop and said that this experience changed their life entirely. Ali, who was a painter at that point who taught art classes in schools, said that after finishing the workshop, he went to his home, emptied his room, gave all his paintings to a friend of his, and “had the faith that this theme is more important than [the] art [of painting],” placing in his room only a single table with a camera on top of it. He started to take photos continuously, read only about photos, and worked everyday. Ali was amazed by the work of the foreign photojournalists he saw in Iraq and felt a great responsibility for taking this task on his shoulders.“Those foreigners came to work in Iraq, the place I was living, and their works were so professional,” said Ali, while explaining how he came to the realization that it would actually be easier for him since he lived here close to the cities and the action, he also added:. “The stories were all around me. I even had more time and greater chances to work on stories from my home.”

Before Metrography, Kurds only had a few photographers and not a single photojournalist. “What has been done in the past was not thought of as photojournalism, it was recording and archiving an event by a random choice,” said Sartep. “We did not have the concept of photojournalism until the establishment of Metrography.” Photojournalism started to develop in the Kurdish region of Iraq after the establishment of Metrography. Ali thinks that “Metrography was the revolution” in photojournalism in Iraq back in the time when it was first established. “But not anymore, Metrography’s vision is not the same as before,” said Ali while explaining that it changed after Kamaran went missing and Sebastian returned to the US. Hawre also shared the same view, saying that: “When Kamaran was still in Metrography, he was trying [to build photojournalism] in Kurdistan, but with Kamaran disappearing, it disappeared too.”

The new generation of Kurdish photojournalists had the opportunity to learn from the more experienced and educated generation of skilled foreign photographers and photojournalists before them. Ali was one of the students who joined the ten-day master class that was offered by Metrography in 2011, taught by four experienced photojournalists and photo editors. “From that day my eyes opened, and not just that, my mind and everything changed. That master class imprinted courage in me to work, this was the point that took me to photojournalism,” said Ali. without the efforts of his lecturers, this would not have been possible: “I learned and used all my experiences in art through journalism to produce my photos in the story that I made in these ten days with the help of my teachers.” They showed the students the photos that have been produced in Iraq by other foreign photographers and taught them how the locals should work on those types of stories. Sartep also participated in this workshop and said that the workshop built his understanding of photojournalism and making stories and that it was his first time being taught by professional photo editors and photojournalists.

How Kurdish Photojournalists Learned their Trade and How They Teach

This generation that was taught by foreign photojournalists are now teaching the new young generation of photographers and photojournalists. For example, Hawre Khalid now has students in Sulaimani, whom he is teaching the basics of photography and the ways to be a photojournalist by profession. Through VII Photo Agency, Ali has offered a 12-week program, where he is mentoring the photographers and helping them to publish their works at the end of the project. Sangar and Younes are some of Arkady’s students in this program. Younes also has workshops for the ones who want to learn about photography.

Kurdish photojournalists have learned how to work in this field by their own attempts, reading and learning about photography, and by the guidance of foreign photojournalists when they cameo work on an assignment in Kurdistan. Sometimes this contact occurs by working closely with them as a guide and fixer to show them around and bring them to their subject. Younes Mohammad, a Kurdish photojournalist from Kurdistan who now works as an international freelance photojournalist, said that at first he was working for free as a fixer just to be close to the photojournalists who come to Kurdistan on assignments. As a result, he learned both about the technique of photography from them and also how to build good connections with other photographers that have helped him in his future career.

These are the alternative ways for the emerging Kurdish photojournalists to learn the skills needed to be a photojournalist and to gain the practical knowledge of photojournalism. Arkady sees that studying photojournalism is not necessary, as “they will give you a bunch of rules and instructions that you cannot go beyond.” He emphasizes that “it is better to create your own experiences and your own works before that, you should have your own freedom of work and exploration.” Besides, Ali thinks that master classes are better than any other ways because they are independent and have less restrictions. In the end, “It depends on the capacity of the one who chooses photojournalism and their willingness to do the work. It requires someone to be patient and try to remain wise in the difficulties.”

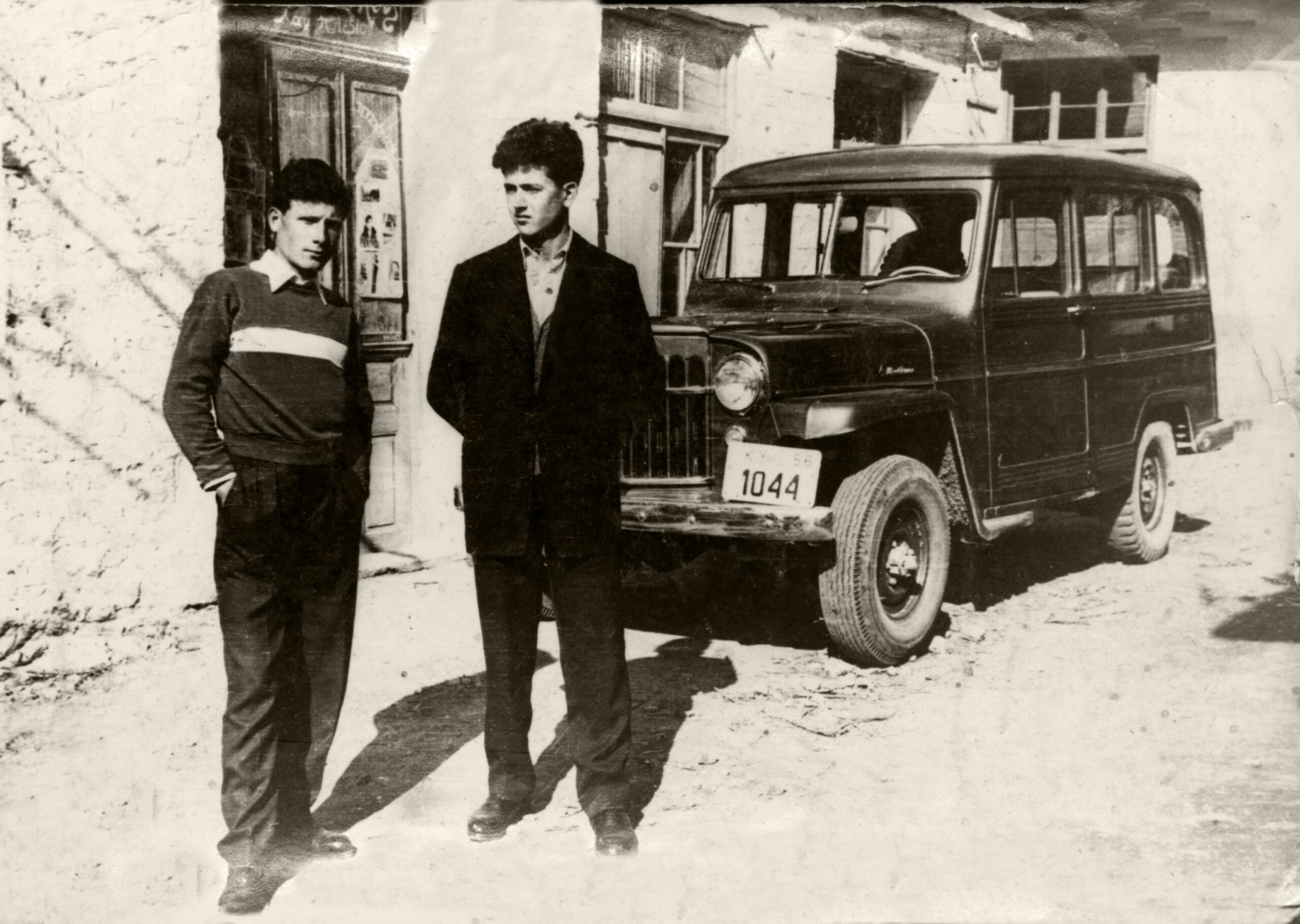

Photo by Sangar Akrayi

One of the most effective ways that photojournalists train themselves is by keeping themselves up to date on a daily basis. On this Sangar says that “seeing other photographers work” is a way to educate your eyes on the photos, as “that is what every photographer has advised me to do as a good way to learn.” They have taken this road to get into the field of journalism in order to tell the stories of their nation from their own perspectives, because until recently there has not been any university teaching photojournalism as a major, or even as a single course in Kurdistan. There is no institute dedicated to train someone who wants to become a photojournalist. Most of the renowned photojournalists who work in Kurdistan now, have come from a different academic background. They have learned photography through their own personal efforts and choose to work as a photojournalist from their passion to that career. As an example, Younes Mohammad had two jobs in Hawler as a business administrator, and he eventually quit both, saying: “I was not enjoying anything in my life anymore.” He was searching for a career that could keep him excited about life and help him to learn everyday. He chose photojournalism. As for Ali, he was an art teacher in a small town near Darbandixan: “Everyday after teaching I was going from school to Baghdad, Basra, Sulaimani or Hawler. Staying for one day, working and then coming back because I had to teach the next morning.” He then quit and chose to be a full time photographer. Sangar was working as a journalist then he shifted his career to a full time photojournalist.

What the local photojournalists in Kurdistan are trying to do, what they are covering, and how their work is different.

Some local photojournalists think that they are connected more to the stories of their country than foreign photojournalists who come frequently to produce a story and leave. Since they are closer to the people and events of their country, they can build a better connection with the topic they are working on. In contrast to this view, Ali Arkadi thinks that the local photojournalists of Iraq occasionally run into problems because of their local ties and should first learn to accept the diverse community of their land to be able to work as a free and independent photojournalist. If not, he says that sometimes foreign photojournalists work better in Iraq, “because as a person they have less customs, traditions, [and other] related restrictions in this region, along with issues of religious acceptance or political issues.” He further explained how in this manner, the foreign photojournalists can generally deliver their message in an unbiased way. Ali’s perspective highlights how working as a local photojournalist in Kurdistan is by no means without its challenges, and demands a great deal of those who choose to take it on as a part or full-time profession.

But if the local photojournalists were willing to work as an unbiased, free, and honest messenger to deliver a true message, they of course will have more access to sources in terms of the language, social and historical background, and knowledge about their subject than someone outside of their country even before they meet their subject in person, allowing them to go deeper into their subject’s life. Ali taught a master class to a group of Yazidi girls who survived the war against ISIS, whom he trained in their camp. “Their photos were deeper and stronger than mine in the camps, because it was their place,” said Ali when recounting his master class. In Ali’s opinion, photojournalists should first go beyond their cities. After they develop themselves, and gain success in their own region and find their ways, they will eventually gain the capacity to apply those skills and transfer their stories anywhere in the world. Ali thinks that by doing your work as a photojournalist, with your stress and late-night work, you will receive the respect you deserve somewhere in the world: “They will see what you have done to be in your position.” He can sense this now while he lives and works abroad.

Hawre Khalid, a Kurdish freelance photojournalist who gave up living in Europe two times in his life to cover the ISIS war within Kurdish borders and report the news of his country, thinks that he can tell the stories of his people better than others because he shares the same issues they have. This helps to produce a more heartfelt portrait of Kurdish society. Younes Mohammad also touched on this topic and said: “I want to talk about the problems I see that are important around me [to the degree] that they have become an internal struggle for me and I feel responsible toward them, by making those stories I can solve this problem.” Younes wants to be the voice of his community and dig more into the core of the problems that exist in his society.“I want to showcase the different reasons that made this situation for the Kurds other than politics and wars, then try to find a long term solution for them.”

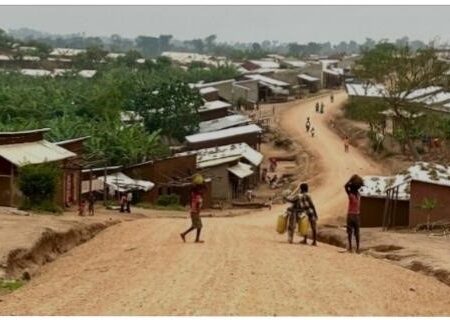

Photo by Younes Mohammad

Younes thinks that although the local photojournalists are not as well-respected as the foreigner photojournalists, they have a heavier burden on their shoulders since they are closely related to the current and future situation of their land. He further elaborated that “if an equal chance to work is given to both local and international photojournalists, the outcome would be different.” About this topic, the co-founder of Metrography Sebastian Meyer wrote: “While Kamaran and his colleagues were only asked to shoot instances of extreme violence, foreign photographers—like myself—were being assigned more subtle, in-depth stories.” 12

Hawre stated that while Western photojournalists come here and just focus on one aspect of our life, saying: “it is important to me to see how a photographer from another country sees my homeland, but most of the time they cannot depict the complete picture, rather they deliver what they want or see to be important.” Kurdish photojournalists have more fleshed-out narratives with more accuracy that take into account the roots of their people and country. “I care more about the stories of my country, which is why I can put more feeling into my work,” said Hawre while explaining his point further. These local photojournalists will focus on the details of the events that are happening more, and their work has more dimensions and depth. Sangar also thinks that he understands the details, rules and restrictions of his country better than someone from outside.

History and identity formation of Kurds: Kurdish photojournalists role in the Kurdish memory and identity formation.

Local photojournalists feel responsible for crafting an accurate image that might help in the future by helping to shed light on a certain lifestyle, event, or cultural aspects of Kurdish life that might have either disappeared or only been remembered by a few. In this way, their work is as much about the future as it is documenting the present or recent past. Sartep Othman hopes that his works can have an impact on the way the history of the Kurds will be presented. “If the photos I have taken in the past few years could have a small contribution in writing a short history of Kurdistan or a city, I will be thrilled.” Kurdish history had been denied under Saddam’s rule, and it is still denied in Iran, Turkey, and Syria. Because of that, there is always that fear in the heart of Kurdish population that there might be another war, invasion, or another attempted annihilation of the Kurdish identity. That is why when Kurdish photojournalists talk about their mission, they always mention forming Kurdish memory and identity.

Due to the difficulty of life for the Kurds who were living in constant wars and the fact that their areas have always been a conflict zone in all four countries containing the Kurdish homeland, Kurds do not have a reliable recorded memory of the past. Some of the archives were destroyed by bombing or fleeing home and leaving everything behind. Other archives that remained were destroyed by our own hands, in fear of being caught by the enemy and used for further revenge. 13 Many Kurds have burned their personal photo albums so that now we are left with very few physical reminders of those past days. Back in the days, Kurds did have greater problems to be concerned about in their lives, such as money, food, and a safe shelter. In other words, they were still fighting for their basic rights of living, and that is why collecting and preserving memories was not a priority for them. Besides, as Younes attests, the value of archiving was not instilled into the population yet. 14

For Kurds, photojournalism is very closely connected with forming an identity because it is amongst the newest tools for recording one’s history and thereby solidifying one’s identity. Even written history is new to the Kurds since in the past, Kurdish history, culture and rituals were passed from a generation to another by the Kurdish songs called “Heyran” and “Dengbêjî,” by the poems left by our classical poets, letters between the intellectuals or papers. As Kurdistan was ruled by different empires and states, Kurds were not the ones who had the opportunity to decide which history gets to be recorded. But now, photojournalists want to fill that gap through their work and contribute to this process of identity formation. On this topic, Ali said: “The things that I have seen in my childhood, my memories was gone undocumented, and Iraq was still going in the same direction, everything is diminished in a pit without being recorded. But no, now I am here and I should document them.” In this way the Kurdish photojournalists serve the writing of modern Kurdish history through their lenses, merging their own experiences with their ideas of the forgotten Kurdish past. “I started to document everything so I can compensate for the things that I have seen in my childhood,” said Ali about his attempts to recall his own childhood “I feel like I am filling the missing spaces of the thing that I have seen before, by documenting them now.”

In similarity to Ali’s views, Neil Shea ,who is a writer for National Geographic and has visited the region many times, also hopes that the young generation of Kurds see what their people have lived through, and will be able to decide “how will we choose what to remember?” for the future, through the work of their photojournalists. He already saw this process occurring and commenting on Hawer Khalid’s work, he stated that Hawre can go beyond his geographical border and can join the wider community of photojournalists and image-makers in the world by his works in the international publications. 15 This applies to the works of all the photojournalists in Kurdistan.

Having their voices heard, they can participate in writing the history of their people. By this they want to create their marks and their identity in their own hands. They are adding to the history of the world with their own history, by their own narration. It is a way to take part in formatting their own identity and history. Younes explained that this new photojournalism is different from what came before through the support of government officials: “[what had been done before] was not done for the creation of a culture within our own society, or to solve a problem, rather it was only for displaying a side to the outside word that is in a way like an embellished face, an embellished nation to show [other] people.”

Conclusion

Although there were local Kurdish photographers that did some work that we can define as photojournalism in the past, Kurdistan did not have local photojournalists whose only and full-time job is searching for stories and taking photos until late the 2000s. This only occurred after the fall of Saddam’s regime by the US in 2003 and the establishment of the first Kurdish photo agency in Iraq. That was the time when Kurdistan was in the peak of its growth. All of this changed after the war against ISIS. The economy collapsed, Kurdistan was again the frontline of a new war, and there was not any master class or workshop for the journalists again. But a significant thing had changed from the past, as now there were a handful of local Kurdish photojournalists that are known internationally. Now, emerging photojournalists have the chance to learn from this generation who we can consider as the first generation of full-time photojournalists in Kurdistan. This will hopefully help the creation of a visual history for the Kurds and take part in the process of forming Kurdish memory and identity for generations to come.

- Kantowicz, Edward R. Coming Apart, Coming Together. 160. ↩

- Meiselas, Susan. Kurdistan in The Shadow of History. xvi. ↩

- Biography, Ali Arkady. https://www.aliarkady.co. ↩

- Hawre Khalid Portfolio, DARS. http://darstprojects.com/hawre-khalid-portfolio. ↩

- Information from my interview with Sartep. ↩

- International Photography Grant. photojournalism-nominee:younes mohammad-WinnersGallery. ↩

- Information from my interview with Sangar. ↩

- Meiselas, Susan. Kurdistan in The Shadow of History. 206. ↩

- Meyer, Sebastian. Under Every Yard of Sky. 89. ↩

- Metrography Agency. “Metrography is the first photo agency in Iraq.” https://www.facebook.com/pg/metrographyagency/about/?ref=page_internal. ↩

- Home page, Metrography. https://metrography.photoshelter.com. ↩

- Meyer, Sebastian. Under Every Yard of Sky. 89. ↩

- Meiselas, Susan. Kurdistan in The Shadow of History. xvi. ↩

- From the interview with Younes. ↩

- Shea, Neil. Through the Smoke, Behind the Curtain. 10. ↩