On October 17, 2019, Lebanese people took the streets of Beirut to protest against new taxation laws, the deterioration of the economic situation, and the corruption of the political class. The demonstrations spread to the entire country, especially major cities, demanding an end to the regime and to corruption. On that day, I met the artist Hayat Nazer in Marty’s square, where the Revolution started. I already knew her because I was following her on Instagram and Facebook. She was born and raised in the Lebanese city of Tripoli in 1987. She had been spending a significant amount of time helping NGOs in vulnerable Lebanese and Palestinian neighborhoods since she was young. She is a self-taught painter and sculptor with a bachelor’s degree in arts and science from Beirut’s Lebanese American University. Her passion for humanitarian work took her from Beirut, where she worked for the United Nations Development Program (UNDP), to London, where she completed an MA in Communication, to Abu Dhabi, where she worked for the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), to New York, Beijing, and Ankara, where she represented the Lebanese Ministry of Social Affairs on the Syrian Refugees question. Her paintings, which are inspired by her humanitarian activities, reflect her actions and her ambition to promote change. I interviewed her for this research project on Wednesday, May 18, 2022.

The Phoenix of the Revolution

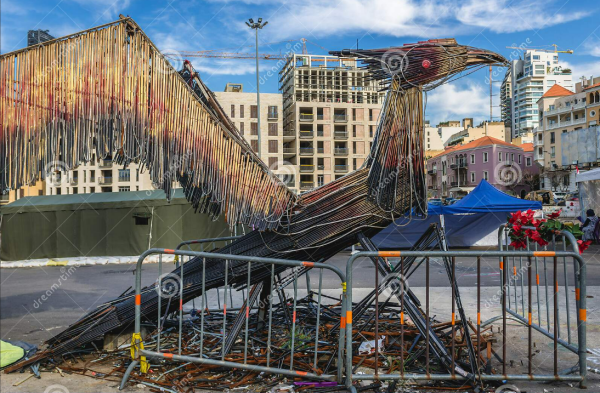

On Independence Day, November 22, 2019, I was driving through Beirut with my friends, and we noticed that some pro-government supporters had destroyed protesters’ tents and burned down the ‘Fist of the Revolution’ statue, a symbol of the Revolution (see Figure 1). Hayat Nazer decided to build a sculpture made of metal rods of broken tents on the destroyed site. She needed help from volunteers and I participated in the construction of the sculpture.

We gathered the protesters’ tents and helped her build the sculpture. We went on the streets and started removing metal rods lying on Martyrs Square. People who had come from all over Lebanon to demonstrate for Independence Day asked us, “why are you removing the metal? What are you going to do?” We told them that we wanted to create a phoenix out of it because a phoenix is a bird that rises from its own ashes every time it burns. Out of nowhere, people began to assist us in creating the Phoenix. Old and young, children and women from all over Lebanon, all religions, sects, and regions worked together to help us, even though they didn’t know each other’s names. Since we were building the Phoenix together, it became a huge symbol of the never-dying revolution. We all cried while building it because it was very emotional. It got a lot of attention from media coverage, and everyone was taking pictures of it. Even the tourists who came to Lebanon and witnessed the revolution took pictures of the Phoenix (see Figure 2).

The Heart of the Revolution

Working with Hayat Nazer was a cathartic experience for us all. It was not the only time we helped her create art in response to social and political issues in Lebanon. As the country descended into months of anti-government protests, Nazer told us that she left her job in communication to pursue art in the hopes of bringing change. During the interview I conducted with her, she told me, “I could not stop myself from succumbing to a desire, so I had to leave my job,” and she added, “with the help of wonderful volunteers!”

Using the same technic, she then created a statue in the shape of a huge heart for Valentine’s Day on February 14, 2020. Since the start of the Lebanese uprising, the protest square in the center of Beirut —Martyrs Square — had been filled with tents erected by revolutionaries. After the protests began against government corruption, the waste scandal, and harsh economic conditions, the country’s creative community turned its attention away from museums, galleries, and other traditional cultural venues to the streets. As a result, Martyrs’ Square practically became an open-air art gallery, with budding young artists and protesters working side by side to capture the spirit of the revolution. Colorful graffiti and murals around the square proclaim the slogans of the revolution: “Words are our weapons.”

In reaction to reports and efforts by the Ministry of Interior to remove such tents, a large number of demonstrators and protesters rushed on January 28, 2020, to resist the Internal Security Forces’ attempt to remove barriers blocking the road around the square and protecting their tents. In memory of these events, we also helped Nazer create the heart-shaped sculpture out of barbed wire with tear gas canisters and stones. Now the heart shines when darkness sets in, and its neon lights illuminate the whole area, casting a heart-shaped shadow on the so-called Wall of Shame, the concrete-and-metal structure built to keep protesters away from the doorsteps of the parliament (see Figure 3).

The Lady of the Port

On August 4, 2020, a massive stockpile of ammonium nitrite exploded in the port of Beirut, killing thousands of people. Over 300,000 people have been displaced as a result of the disaster. Lebanon had already been through months of political upheaval, economic collapse, and a coronavirus outbreak. It brought a small country to a halt under all this pressure. “Our hearts were shattered by the explosion. We were taken aback. We were traumatized, but in Lebanon, “we’re all damaged,” as one volunteer I met when helping Hayat Nazer told me. Hayat Nazer, like many other citizens, volunteered to clear up the rubble and restore the port to its former grandeur. I was also a volunteer, and this is when I met her. She told us she wanted to build a statue from cups, pieces of metal like iron, and broken glass from shattered houses, and she encouraged us to come together and contribute to building the statue. She needed our help to gather material to build an inspirational figure made of glass and wreckage from the blast. I cannot remember a time when Lebanon was quiet, but thanks to her, after the shock of the explosion, we figured out how to turn our grief and sorrow into an amazing work of art. When we feel down, we attempt to help fix the situation and heal people thanks to art. Nazer explained to us that she wanted her piece of art to show that she believed people would accept reality and try to rebuild themselves.

We roamed the street of Beirut for weeks, collecting twisted metal, shattered glass, and people’s trash to put in the artwork. We visited people’s homes and told them we wanted them to give us anything they could think of to make the parts of the sculpture we were about to build. Some people gave us priceless items, including mementos from their youth, heirlooms from their grandparents who died in the civil war, and items they wanted to save for their children.

We witnessed so much fear and loneliness that it broke our hearts when these people gave us such intimate things. For example, an old man gave us a clock to put beside the sculpture. He was living in a small house because his family had left him. He was very sad. When we finished the sculpture, we came back to his house and took him to the place where we had built the sculpture. He was happy and told us he felt that the things that we had used to build the sculpture made people feel happy and that it helped him get rid of the sorrow in his heart.

When we had gathered enough things, we finally assembled them to shape the sculpture into the form of a young woman holding the Lebanese flag, her hair and clothes flowing in the breeze (see Figure 4). The statue also included the old man’s broken clock stuck at 6:08, at the time of the explosion. Finally, the, but had yet to be given a name. We baptized her “the lady of the port.”

The Healing Power of Art

After volunteering to help Hayat Nazer build these amazing pieces of art, I sent her an invitation telling her I wanted to interview her to ask some questions about what feelings the pieces of art provoke in someone. She told me that she had had two original ideas. One before the explosion and one after the explosion. The first original idea was to build a statue about what women were going through in Lebanon and the world. The second original idea came to her after the explosion when she was gathering rubble and broken glass: this statue should be a woman that represents Beirut, which is suffering a lot. She added, “my source of inspiration was to let people see their inspiration in art or by art. There are many impacts that changed in my life through art with the help of amazing volunteers.” “My message to Lebanese people was to tell them that art can heal bad emotions and my message to the Lebanese students is to encourage and motivate themselves by doing a piece of art.” “I want them to recognize their pain, their suffering, to accept it yet turn it into their strength and beauty, just like the statue.”

Like many other people, Nazer will never ever forget what happened on August 4, and she will always send substantial donations to support people affected by the explosion. It will be forever in their memories, as this horrible catastrophe is still fresh in people’s minds. But her art gives us hope. The statue of the girl has a character of elegance and beauty that was built out of destruction and pain. We all have her inside us. But look at her gesture: her leg is starting to move forward, and her second hand is up in the air just as we need to do, to move forward.

Nazer claimed that she would not have been able to effect the change she desired to see in the world if she had not focused on her art. For her, the Lady of the Port, the Heart, and the Phoenix were meant to affect the natural world. When the people of Beirut discovered this unidentified statue made of shattered glass and materials from the homes of the victims of the blast, they told us they found the sculpture powerful and hopeful because it represented Beirut’s desire to emerge from the ruins. We also reached a broader audience through social media: for every piece of art we volunteered to create, we posted on Hayat Nazer’s Instagram account, where we received many beautiful comments. For example, when we finished the sculpture in the port and posted the picture on Instagram, many people commented that it was fabulous and that it healed their pain. Most people told us the historical events they went through changed the way they saw art. Before the explosion, they thought it was nice to see anyone creating a piece of art, but they did not care much about it. After the explosion, when we, volunteers, were building Nazer’s sculpture, people told us that the sculpture healed the sorrow in their hearts.

Since the beginning of the revolution, the contribution of Lebanese and exiled artists to helping the Lebanese population has not been limited to plastic arts. I also discussed with Wassim Joseph Slaiby, a Lebanese-Canadian music industry executive, talent manager, entrepreneur, and philanthropist, better known as “SAL.” He was born on November 16, 1979, in Gazer, Lebanon. When he was ten years old, his father died. When he was fifteen years old, he fled the Lebanese Civil War and immigrated to Canada without his family. He lived first in Montréal and moved to Ottawa in his late teens. In the midst of the pandemic and after the explosion of August 4, he told me that some organizations he collaborated with abroad and in Lebanon, started to send substantial donations to support people that got infected or injured by the explosion.

Wassim Joseph Slaiby’s testimony highlights the fact that even though Hayat Nazer’s pieces of art were unique and original, she was not the only Lebanese artist who felt concerned and committed to responding to the Lebanese crisis. Hayat Nazer is an amazing person that I met and interviewed. I’m very glad that I volunteered to work with her in building the pieces of art she decided to build. Two of these pieces, the Lady and the Phoenix, left something very deep in our hearts.

Very insightful and engaging.

Jouliana you did an amazing job on the research paper it is well written and engaging.