Treaties, Charters and the Incursion of ‘Super Stores‘

In modern major cities, the department store made a dramatic appearance in the middle of the nineteenth century, and permanently reshaped shopping habits, as well as the definition of service and luxury. Similar developments were under way in London (with Whiteleys), in Paris (Le Bon Marché) and in New York (Stewart’s).[1] If one were to define the global concept of retail shops, it would be summed up in one sentence: “Having different cultures from all over the world under one roof.”

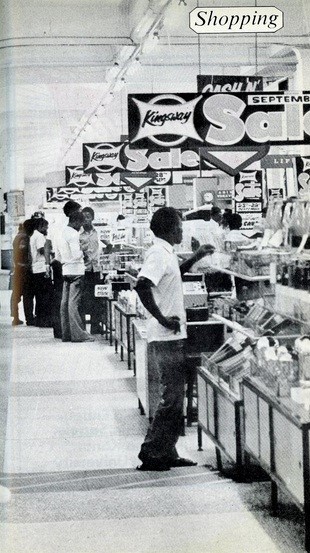

From top left to right: The interior of Le Bon Marché in Paris; Kingsway in Ibadan, Nigeria; Sokos department store building in Multimäki, Kuopio, Finland; Au bon marché; Shoprite images in Ibadan and South Africa.[2]

The middle of the nineteenth century witnessed several European companies struggling to have a foothold in West Africa and in particular the lower Niger Delta. The pursuit of a trade monopoly in the Niger Delta was one the many reasons for the annexation of Lagos in 1861. Large British companies merged in 1879 into the United African Company (UAC), which was later chartered by the British colonial government as the Royal Niger Company. The company signed a treaty with the local chiefs, which gave the company a monopoly in trade matters over the Niger Delta. Some of the companies that operated in Nigeria and still do today are UAC, G. B. Olivant, John Holt, A. G. Leventis, PZ (Paterson Zochonis) Cussons Plc, UTC (Union Trading Company), CFAO (Compagnie Française de l’Afrique Occidentale), SCOA (The Trading Company in West Africa) and later Nigeria Breweries Limited. These establishments led to the emergence of middlemen and agents, the introduction of advertising and part-time and full-time traders, although on a small scale. Nigeria, as well as other bordering African countries were indeed a fertile trading ground for economic activities to thrive for Britain and other European countries like France. According to Ezekiel Tom, “Nigeria was not only a source of raw materials to feed the manufacturing plants abroad but also a ready market for products from European firms.”[3] We have learnt in the first half of the course, anchored by Professor Jeremy Adelman, about the ways in which the Second Industrial Revolution was associated with a second imperial wave[4] and how European interest in Africa grew sporadically. Politically, the economy of the colonial state was run by its dictates and was intended to subjugate, exploit and dominate the Nigerian people and their resources. Its pattern of penetration could be traced from the coast to the hinterland and its nature was exploitative. The imperialists scattered all over the African continent concentrated only on economic activities beneficial to the colonial state, and were thereby disarticulated domestically. “It promoted the interest of its centers of activities – urban settlements – and thereby neglected the rural mass settlements. The colonial political economy was therefore grossly uneven. It was also dichotomized into the state of public and private sectors, with the former as the instrument for the promotion and development of the latter.”[5]

Ezekiel Tom demonstrates in his work that how the colonial authorities prohibited the people from the production and sales of certain products, notably the local gin called ‘ufofop’ or ‘Kaikai’. [6] He noted that “it was offensive to produce, sell, consume or aid in any of the aforementioned activities. Those who engaged in the business had to go right down into the forest to produce it. By so doing the people’s attitude to entrepreneurship and commerce was mangled and they were denied the right incentives to make risk – worthy ventures and decisions worth taking.”[7] And so, big commercial establishments like the United African Company, UTC, G. B. Olivant, etc. prevailed over every component of Nigeria’s economic and commercial life at that time, choking any attempt by small indigenous marketing firms to acquire experience and expertise, and also made it the development of marketing techniques and practices very difficult. According to Ogwo and Nkammbe (2009), one of the consequences of the monopoly that the companies extorted from the people was that it deprived local inhabitants of the benefits of free trade and the advantages of choice in a competitive market.

UAC headquarters in Lagos, Nigeria.

Retail Shops in Nigeria: From Kingsway to Shoprite and Consumer Behavior

Kingsway Stores was established in 1948. It was the first and largest departmental store and modern retail shop in Nigeria at that time, and it rapidly spread its tentacles to other parts of the country. It stocked itself with a mixture of general consumer goods, fabrics and various items appealing to a wide section of the populace. The store rapidly became the toast of many across the country, especially with the introduction of its quick service restaurants known as Kingsway Rendezvous. Owned by the UAC, it was the place to be for fun and bargain seekers.

As it grew economically, it also began to change the ways in which society defined luxury, taste, fun and even achievement. A newspaper source gives an account of how school children would sometimes get flogged for sneaking out to go play around the Kingsway store. Once in a while, some of the teachers who scolded them were also culprits. The source further reveals that “kids living with their parents at Ebute Metta, in Lagos, would always go to Kingsway Stores for most of their needs. They would save their pocket monies for meat pies, burgers and the rest just to feel good.”[8] This shows how there was gradually a shift from patronizing locally-made consumables and products to shopping in these ‘super stores’ as they were also called.

“I remember those days when our parents got us shoes from ‘Lennards Stores’. Their shoes were superior and of high quality and children that had the opportunity of getting things from those places were always proud of what they had and it gave us the societal status of being among the elites,” Mrs. Mojisola Ojo told me in an interview.

As a woman who lived through the 1960s, Mrs. Ojo sheds light on how only those of high income could buy things from retail shops like Kingsway and Leventis in those days. Their items were of high quality and the shops were located in cities and urban areas. The downside to this was that it created socio-economic segregation among the peoples. The rich were the main customers of these retail outlets and like Dotun Abereagba, a 56 years old accountant, said “the days of Leventis and Kingsway were spectacular because they were for the rich and middle class, and their children.” On one side were the rich and middle-class who could afford things from such shops and those who could only afford ‘low-grade’ used clothes or locally made materials or products. And so, there was this rather subconscious longing among both the young and middle-aged to climb up the economic ladder so that they could also have the purchasing power to patronize those super stores. It was even a thing of pride to say “I want to go visit Leventis or Kingsway”. There were also special holiday seasons like Christmas when the stores organized for children to visit “Father Christmas” and receive gifts from him, mostly preceded by exciting adventures of taking electronic train rides through the Christmas groves specially constructed and lavishly decorated in exciting colours and lights of the season. Dotun recalls, “Kingsway started the Father Christmas for children. I used to take my children to Father Christmas at the Warri Kingsway, and by the time they were done, their pocket and hands would be filled with gifts.”

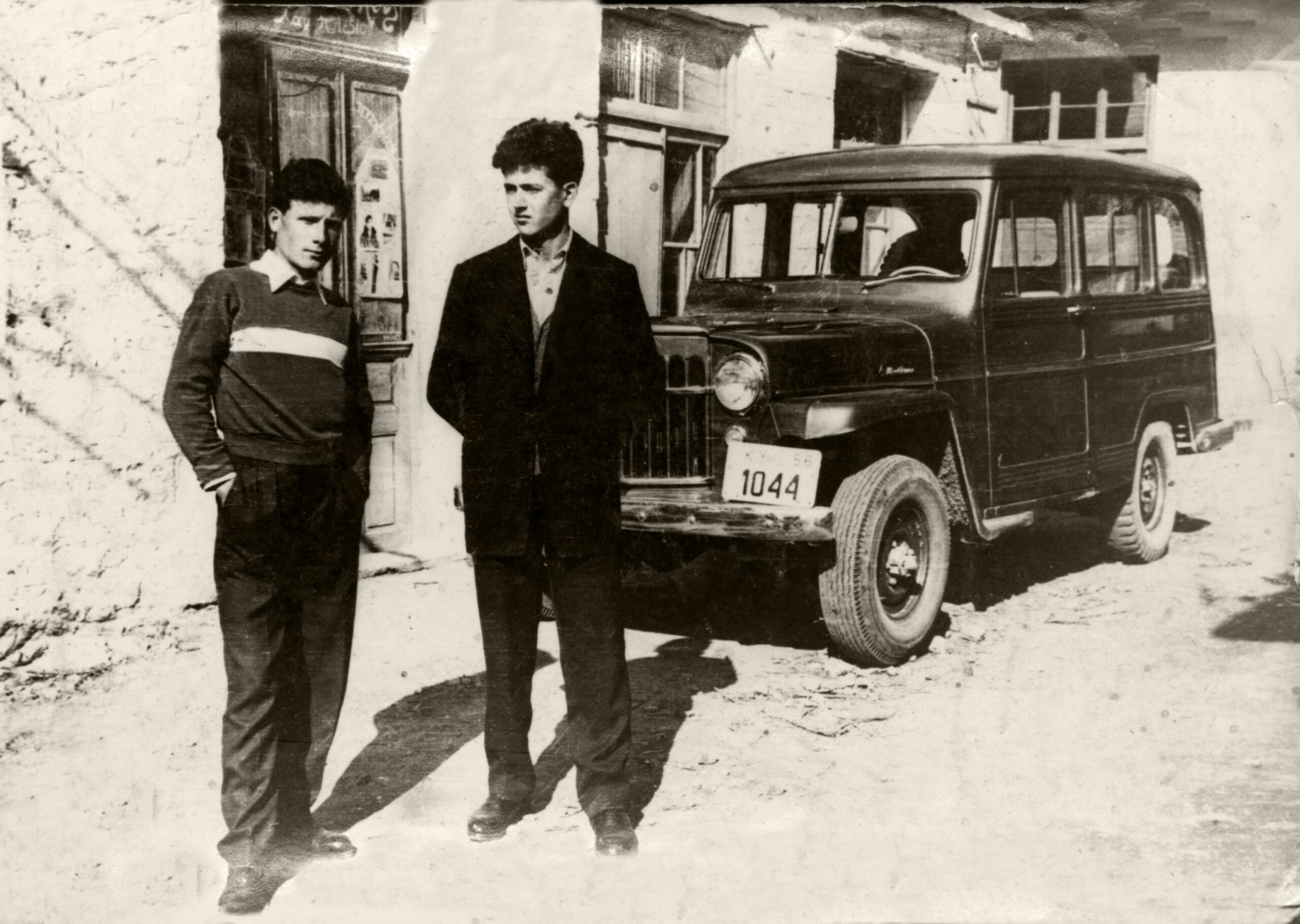

Kingsway in the 60s

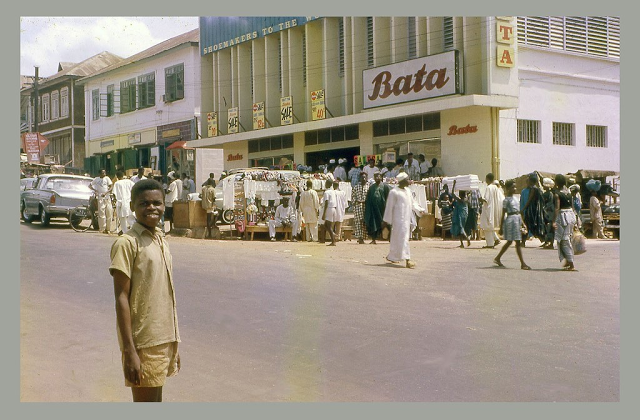

These mega stores also seemed to pose as a center of attraction for many who were fascinated and lured by their uniquely built infrastructures. Dotun noted that “The first elevator I saw and used in my life was at Kingsway. That alone was an attraction. People were always willing to go there and make use of the elevator, and you will end up buying something. For me, it was a place I did shopping for frozen foods, because they already preserved them for those of us who had no fridge at home.” Also, in making further research, I came across a post on flickr.com by Eric Chicago who stated that “The one department store in Ibadan. European food products could be purchased here–even ice cream. Note the Christmas tree decorations on the outside.” The image below was captured by Chicago.

Kingsway Store in Downtown Ibadan at Christmas

Kingsway had about 13 modern department stores and supermarkets in major cities of the country, employing around 1,000 people. This boosted employment and the nation’s GDP. It created employment opportunities as well for school certificate holders who migrated from outside the cities to engage retail giants like Leventis, UTC, Kingsway. This constituted a border crossing from countryside to city and was an important contribution to Nigeria’s urbanization. Additionally, people from bordering countries would migrate from places like Abidjan to regions such as Lagos where these stores were situated in pursuit of better jobs and pay. The driving force was arguably the search for better livelihood and opportunities. These big retail giants like Kingsway, Leventis, UTC (and present-day Shoprite) were at the forefront of bringing these dreams to reality.

The “Indigenization Decree” and the Decline of the Retail Shops

In 1972, the federal military government of Nigeria issued an “Indigenization Promotion Decree.” It became effective on March 31, 1974, with the purpose to eliminate or restrict foreign ownership in 55 non-agricultural sectors of the economy. According to the literature, “The Decree also established the Nigerian Enterprises Promotion Board (NEPB), with power to enforce the Decree nationwide…”[9] This decree by the military government was the genesis of the problem for most of these retail shops, which were foreign-owned firms. They therefore had to bend to the harsh dictates that came with the decree. The crisis deepened for the super stores during the structural adjustment program of the General Sanni Abacha regime; they could no longer bring in imported items. According to a newspaper source, “Kingsway liquidated, Leventis downsized and eventually closed all of its retail outlets. UACN, despite being a major supplier of items for retail businesses, also felt the impact and had to downsize. This affected Domino stores as it lost a huge clientele base.”[10] However, in light of these manifold challenges that plagued these super stores from the 1970s onwards their gradual fall did not just leave a vacuum, but rather, it led to the rise of other super stores from the late 20th centuries onwards of which Shoprite is a notable example.

The Rise of ShopRite in Nigeria (2005 to the Present)

ShopRite (which opened its first store in Lagos in December 2005), just like its predecessors, makes available a variety of products from across borders. With the subsequent liberalization of importation and the setting up of packaging industries that were previously non-existent, retail shops like Shoprite, Dominos etc., started to make waves across regions of the country. According to sources the Guardian Newspaper, “The presence of ShopRite in any mall automatically changes the outlook and prestige attached to the mall, because ShopRite is now a popular brand of retail stores in Lagos and big cities in the country. It is becoming a culture for the malls to be flooded with people at weekends, the days when most workers have time to shop, hence the overflow.”

The modern-day superstores have been able to create specific features that attract consumers. These include price tags on each product, having a variety of items in one place, and goods often times being offered at low prices from reduced margins. Many times, they preserve their fresh products, throw open to the public promotional offers and with receipts, consumers can report or return damaged products, which is a rare occurrence in other shops. This has fostered socio-economic changes among their customers and the society in general. Their wants, specifications, tastes, and by extension, choice of residence have begun to evolve around the satisfaction derived from these big retail shops. An online Vanguard newspaper source reveals an interview with a Manager at the Lekki branch of Shoprite, Adenike Osunoiki, who said, “we are aware of other operators’ prices; hence, we combine excellent service and a competitive range to keep customers coming for more.”

Mr. Segun Sanusi, in an interview, buttressed the statement that Adenike Osunoiki made: “They have different kinds of products in the same place with standardized prices that builds a sense of trust against being cheated…they provide one with a lot of choices of products I want. They kind of make me want to buy bigger.” On whether they are capable of running other stores out of business, Osunoiki said,

“The others cannot liquidate super stores like ShopRite, which is large with roots in South Africa. Both of them will exist side by side because consumers need both of them. They both need to make provision for what the other is lacking.”

Conclusion

We have come to see through the blend of both primary and secondary sources how super stores such as Kingsway and Shoprite have over the years contributed to a significant change in the social and economic lives of the Nigerian people and by extension, how they expand global economic relations. Today, Nigeria, like many other developing countries around the world, has become a new commercial hub for retailers with the emergence of superstores dotting major cities. Superstores are back in town, bigger and better than what they used to be. New shopping malls are also springing up, relations across borders are getting more interconnected and by effect, social and economic changes in the lives of its customers are trending upwards.

[1] Gunther Barth, “The Department Store,” in City People: The Rise of Modern City Culture in Nineteenth-Century America. (Oxford University Press, 1980) pp 110–47.

[2] From top left to right, you have: The interior of Le Bon Marché in Paris; Kingsway in Ibadan, Nigeria; Sokos department store building in Multimäki, Kuopio, Finland; Au bon marché; Shoprite images in Ibadan and South Africa.

[3] The Impact of Colonialism on the Development of Marketing in Nigeria: A Dyadic Analysis. Ebitu, Ezekiel Tom, Ph.D. Department of Marketing, University of Calabar, Calabar, Nigeria. Pg.4; British Journal of Marketing Studies Vol.4, No.2, pp.1-7, March 2016. Published by European Centre for Research Training and Development UK (www.eajournals.org)

[4] Global History Lab: Lecture 14, Segment 3; Second Imperial Wave: Africa.

[5] Agi, 1998.

[6] Ufofop or kaikai was a locally made gin indigenous to the Calabar speaking people in Akwa Ibom State, Nigeria. It is brewed from the palm wine, with two hands.

[7] Ebitu 2016.

[8] punchng.com/companies-brands-that-thrilled-nigerians-in-the-past/

[9] Jerome F. Donovan, ‘Nigeria after “Indigenization”:Is There Any Room Left for the American Businessman?’ pg.602 (International Lawyer, Vol. 8, No. 3)

[10] https://m.guardian.ng/business-services/the-return-of-super-stores-in-nigeria/amp/