Abstract

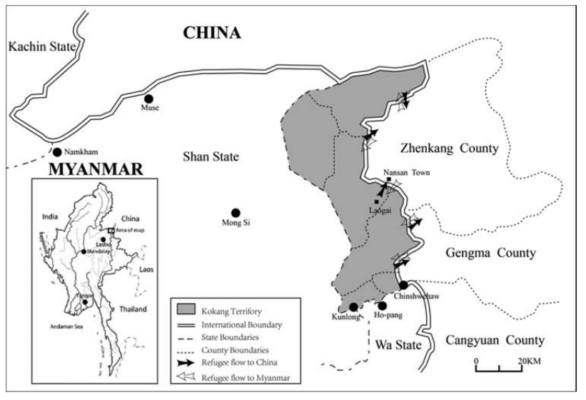

One of the Self Administration Zones in Myanmar, Special Administrative Zone (1), in the Kokang region was founded after the signing ceasefire in 1989 between the military (Tatmadaw) and Myanmar National Democratic Alliance Army (MNDAA). The region has held a fascinating history not only because of the historical background but also because of its political economy that is strongly dependent on China’s investments, currency, language, and social culture, even though conflicts and battles between the Myanmar National Democratic Alliance Army (MNDAA) and the military (Tatmadaw) are continuous despite signing a ceasefire. At the same time, the Kokang region’s economy is disparate from others in Myanmar as they make their income from also the sale of opium and casinos. Economic development has remarkably improved in the region after the coup of 2021, making it diverge even more significantly from other states in Myanmar. According to geopolitics, the Laukkaing, capital city of the Kokang region, has played an important role of the trade corridor in the China (Yunnan)-Myanmar (Yangon)-Indian Ocean Maritime Route (Maritime-Highway-Railway Transportation Network) which can give a direct trade route to Indian Ocean from China (Yunnan). On the other hand, the Chinese Government wants peace and stability for economic benefits for implementing the Silk Road and the Maritime Silk Road Strategy, oil and gas pipelines, infrastructure and protection for ethnic Chinese in the Kokang area (Xue Li, 2015). This research will look into the economic development of the region to understand how the Kokang has developed over the last 30 years differently than any of the other regions in Myanmar.

Introduction

Kokang region, situated in the northern part of Shan State, is composed of a population with an ethnicity of 90 percent Han Chinese yet all live in and are recognized as Myanmar citizens. Its history shows a complex pattern of migration where after the independence of Myanmar in 1947, the region came under the Myanmar government but could not be fully controlled by their direct administration until today. The economy of Kokang is fascinating and complex as its only economy is what is referred to as a ‘war economy’, developed by warlords and opium traders that came and went from China to Myanmar, making profits from border regions in the 1950s and 1960s. At the same time, Kokang has become a buffer zone. The region exhibits ambiguous structures and lacks a clear economic or foreign policy due to its influence by China and other ethnic armed groups (EAOs) in Myanmar. The power seizure by the military regime (Tatmataw) has given an unbelievably massive development and investment from China, especially in Yunnan. The economy of the Kokang region is changing from according to the political and border situation of Myanmar and China.

Historical Background

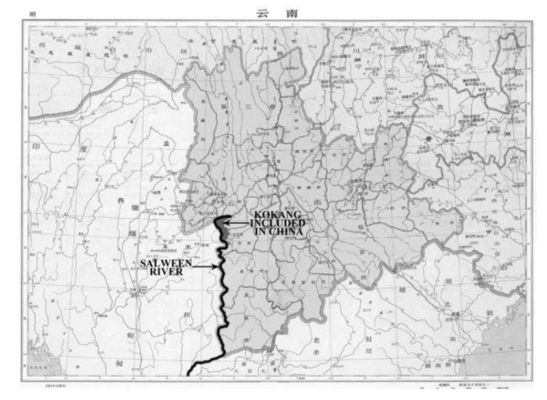

The region’s history is marked by a complex bordering past, including territorial issues, conflicts with the neighboring country, China, and the shaping of political boundaries. The last ‘Ming’ emperor fled in the mid-1600s to Yunnan China, reaching the border of Ava where the new Manchu “Qing” dynasty ruled until 1912. The new ‘Qing’ density was trusted and followed by the thousands of Ming loyalists, among them ‘Yang Gaosho’. Succeeded by the Yunnan emperor and their descendants that ruled for over 200 years, the first ‘Heng’ of ‘Kokang’ founded (Lost Footsteps, n.d.). The Kokang region was the signature of the fall of the Ming dynasty and the migration of Yunan Mandarin Chinese to border areas of Myanmar.

Myanmar was ruled by the British Empire from 1824 to 1948 when Myanmar (Burma) was a province of the British Indian Empire. Under the Peking Convention of 1897, the Kokang region was under British India. At that time, Beijing was not fully controlled by the empire and the British empire lacked control of the Kokang region. It was under the control of Shan Saopha during this time. Myanmar gained independence in the year of 1948, though this independence did not impact the Kokang because nothing changed as much as British colonial rule.

In the early periods of this timeline, the Yang Family, Chinese nobles, were autonomously administered throughout World War 2. The lack of attention to China-Myanmar areas by the British Empire gave the Yang Family full autonomy. In the 1950s, the Chinese Kuomintang retreated from China and burst into the Shan State. Afterward, the Communist Party of Burma (CPB) held power and control over the Kokang ethnicity until early 1989.

In the 1960s, the Kokang region was under the control of the Communist Party of Burma (CPB) which was against the Myanmar Government (the Military). In 1989, the Kokang ethnicity was the first ethnicity who mutinied the CPB. After the separation from CPB, Kokang signed a peace agreement with the government (the military) and the Kokang region became Special Region 1.

Subsequently, the ceasefire agreement was signed between Lieutenant General Khin Nyunt and the Kokang commander, Peng Jiasheng (Phone Kyar Shin). After establishing Special Region 1, the Myanmar National Democratic Alliance Army (MNDAA) was founded on March 11, 1989 (ISP Peace Desk, n.d.) and Peng became the leader. In 2009, the military (Tatmadaw) forced ethnic armed groups who signed a ceasefire agreement into the Border Guard Force (BGF) and tensions and conflicts increased.

As a result, the leader, Peng, had to flee from the Kokang and Tatmataw and some commanders in MNDAA became the leader of the Kokang region. However, after reinforcement from the Kachin Independence Army (KIA), Peng officially announced that he would take over Kokang in 2015. After the announcement, battles between Peng and Tatmadaw started in February. After shells fell on the border of China from the battle, the Chinese government pressured and gave strong calls to restore peace in the China-Myanmar border region so the battle was announced as a unilateral ceasefire (Timothy Mclaughlin & Hnin Yadana Zaw, 2015).

After massive clashes in 2015, MNDAA leaders started new political strategies by extending connections with other EAOs as they joined the United Nationalities Federal Council and the Federal Political Negotiation and Consultative Council. Moreover, they widened their interconnection with TNLA and AA (Oo, 2023). When the Spring Revolution took place in 2021, MNDAA provided military training to resistance fighters which gave them broader influences in Shan State. Simultaneously, China was prohibited from getting involved by Western influences in the Spring Revolution Forces. National Unity and Peacemaking Coordination Committee (NSPNC) and the Three Brotherhood Alliance met in the eastern Shan State with Mr. Guo Bao, Special Envoy for Foreign Affairs of China’s Yunnan Province (ISP Myanmar, 2023).

Today in the Kokang, the MNDAA’s aim is to fight for the Kokang identity and self-administration but with a dependency on China in closer cooperation with the illegal drug trade and border trades. However, throughout their historical timeline they have faced complex political situations, battles with other armed groups, and the military (Tatmadaw). Remarkably, they fought for their self-administration zone which is an escape from the influence and power of the regime. They have managed different and various ways to survive as a small ethnic group and achieve influence and success.

Economy with illegal trades

The complex and unstable political situations in Kokang have resulted in abject poverty. Local people trade in sugarcane, tea, and opium to make their livelihoods. Because of the geographical situation – high mountain hills, it is difficult to connect with other States and Regions for Kokang. Due to the poor transportation system and language barriers, Kokang was isolated from the mainland of the country which is why they tie closer to China.

Previously, the cultivation of rice and crops, hunting for meat, and additional utilitarians was fully enough for households and only tea and wildlife products were traded (UNODC, 2003). However, during the Opium War of 1839-1842, the Chinese promoted opium cultivation to British traders for distribution and import. The opium cultivation came to Kokang and Wa Regions as a business opportunity for locals to create a war economy. The soil and weather of the Kokang region were suitable for growing poppies which became the main export product for the State’s revenue. As a consequence of the opium war, the borderline area of China and Myanmar in the territories of Kokang and Wa, became the main areas of opium cultivation. From that time, Kokang and Wa regions became the main opium cultivation and distribution regions in the area during the British Colonial era.

The Kokang region heavily relied on the drug trade as its primary income for decades. Famous warlords and drug traffickers, Olive Yang and Peng Jiasheng, controlled drug trafficking for decades in the China- Myanmar – Thai border area and the Golden Triangle Area. They became power actors in the history of the Kokang. They also became leaders of the group who played in administrative sectors and made negotiations with the Military (Tatmadaw) in the peace process. However, in the 2000s, MNDAA introduced ‘opium free by 2003’ with the force of China and international pressure. To replace the income of the region, Tatmadaw allowed casinos to be established in Laukkai. The Kokang region was creating substantial revenue despite facing instability, conflicts, and pressures from China, mainly through drug trafficking.

Apart from opium cultivation, the region did not have any extractive sectors or industries. After the peace agreement this changed as the government (the military) gave an opportunity to the Kokang region to allow gambling and casinos. This was allowed as an investment, especially for Chinese companies and as tourist attractions for Chinese citizens from Yunnan province. Even though they had investments from China, local people in the Kokang region remained in poverty despite these changes. The profits were divided between Chinese investors and authorities of Kokang, MNDAA, and Kokang Border Guard Force, not reaching local citizens.

After Bai Suocheng took power from Peng in the 2000s, drugs were fully controlled at the end of 2002 for the first time in over 200 years. Moreover, local businesses were encouraged such as agriculture (mainly sugarcane) projects and language education. As of 2012, sugarcane had emerged as Kokang’s second-largest agriculture, behind only gambling. Currently, numerous projects are underway, including the construction of 125 cross-border industrial parks. These endeavors are poised to significantly bolster economic progress in Kokang (Xue Li, 2015).

Despite having armed conflicts, leaders of the Kokang region intend to bring peace and development to their region by persuading international investors to invest in its casinos. One of their main political goals is to get their territory back. A main economic goal is to make their region, especially Laukkai as the capital of Kokang, into a casino and gaming city like Macau (Nanda, 2020). There is a strong vision to attract airlines to Laukkai and to run casinos legally under Gambling Law that welcomes foreign visitors from all over the world. In an interview in 2020 with Frontier Myanmar and The Kokang lawmaker, U Kyaw Ni Naing, the economic opportunities in Laukkai, Kokang were explained. He told Frontier that “Gambling Law approval may give Laukkai investment from the international. Additionally, tax revenues for government and job opportunities for local people” (Nanda, 2020).

According to Frontier Myanmar, a rare opportunity to visit Laukkai after the Covid-19 outbreak came in 2020 where it was reported that “casinos operate 24 hours a day even though 9 am to 5 am curfew has been in place since the 2015 attack”. The Nightlife of Laukkai is filled with casinos, hotels, restaurants, and entertainment. Casinos operate under Myanmar’s Gambling Law under the Union Government of Myanmar and they refer to themselves as ‘companies’ rather than ‘casinos’. On the other hand, the local population is unable to operate casinos as approximately 80% of casino employees are from China (UNLOC, 2003).

BRI and trade

Despite its complex political situation and opium trade, the Kokang region is strategically situated along the important geopolitical area of the China-Myanmar Indian Ocean trade route which can give access to China (Yunnan Province) to the Indian Ocean and markets (Lintner, 2023). According to the Institute of Strategy and Policy Myanmar, a new rail-road trade route is part of the grand strategic plan of China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) will be built by passing through the Chinshwehaw a cross-border town situated in Laukkai Township, Kokang region. China-Myanmar-Indian Ocean trade route is a part of the early harvest projects in BRI as China can get trade routes to the Indian Ocean directly which makes Chinshwehaw more strategically important to China. A rail-road-Indian Ocean route will connect Chengdu in Sichuan province to Yunnan province, and from there to northern Shan State, until finally arriving through the Yangon port to Singapore. A trade route connecting Chongqing is also planned for southwest China to Laos, Thailand, and Myanmar. A maritime route exists that already directly connects the Beibu Gulf port in China’s Guangxi province to the Yangon port (Three New China-Myanmar Cross-Border Trade Routes – ISP-Myanmar, 2023). New trade routes are emerging since the coup of Myanmar in 2021 but China and Myanmar have already been planning the China Myanmar Economic Belt Road (CMEC) since 20xx. When Wang Yi, Foreign Minister of the Republic of China, came to Myanmar in 2018, the elected government of Myanmar, the NLD government, met and discussed the CMEC projects in Myanmar which are part of BRI. Both governments agreed to implement 33 projects in Myanmar under CMEC but some projects are under early harvest. Among them, China Myanmar Cross border economic cooperation zones (CBECZ) are under the early harvest list and Chinshwehaw-Linchang CBECZ is included. The rest of the two are Kanpitiet-tengchong, and Muse-Shweli which are also important not only for China-Myanmar trade but also for the grandmaster plan of China. BRI projects highlight the Kokang region as strategically important, resulting in the region engaging in legal trade with China. At the same time, the region experienced significant improvements and development due to both legal and illegal investments from China resulting from the megaprojects.

Chinshwehaw border station is the second largest trade station in Myanmar. It is situated in the Kokang Region. Trade route connection was established between the capital city, Laukkai and Linchang, China. According to the future plan, there will be infrastructure, a core zone, and high-tech infrastructure. Not only is the border station improved, but also both countries agreed to implement projects under CMEC which can connect and support the border gate (ISP Myanmar China Desk, n.d.).

The Kokang Region was highlighted and stunned under the megaproject

Figure(10): A memorial to Pheung Kya-shin in Mongla in March 2022. Source- The Kokangof CMEC and cross-border projects are planned. Despite the unstable situation in Kokang marked by continuous conflict between the Tatmadaw, MNDAA, Kokang BGF, and the Kokang Militia, there are claims that the Chinese government, particularly the Yunnan government, has compelled Myanmar to persistently implement projects in the region due to its geographical importance for the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI).

Status after coup

The regime took over Myanmar in February 2021. After this point, conflicts between the military (Tatmadaw), Ethnic Armed Organizations (EAOs), and People Defense Force (PDFs) have arisen and led to economic and food crises. Along with these, opium trading, cross-border crimes, and illegal trade have returned back to the Kokang region. Not only in Kokang, but also the Wa Self-Administered Region and the NDAA-controlled area have become the center of web crimes.

As the Self-Administration area became out of control of the regime, Illegal gambling and telecommunications fraud have been found to be widespread in the region after the coup, Transnational crime networks have resumed under the control of leaders in Kokang Region and the largest casinos in Kokang and Myawaddy (United States Institute of Peace, 2021).

The border areas in China- Myanmar are heavily dependent on China for most of everything, from business, investments, trade, transportation, tourism, to even currency. After the Covid-19 pandemic began, these areas nearly stopped completely due to the restrictions and lockdowns of both countries. In 2021, the regime locked down Laukkai township when more than 100 cases Covid-19 positive were found (Irrawaddy, 2021). Both the coup and Covid-19 pushed the Kokang region to unexpected success. Kokang was fully filled with entertainment and illegal companies that are also related to illegal telecommunications. Laukkai became massively developed and populated after the coup when advertisements related to telecommunication companies’ job offers, which are almost five times the ordinary payroll in Myanmar, spread on the TikTok and WeChat applications. Many young people felt the loss of their future because of both disasters. They came for better promising jobs in Chinese companies but some ended up as human trafficking in those illegal companies. According to the Institute of Strategy and Policy Myanmar, Thai nationalists were trafficked in Laukkai and the same cases have been found in other Self-Administered Regions (SAR) (ISP Myanmar, 2023).

Despite the crimes and use of heroin dating back to old Kokang history, local people who are living and working in those companies have different points of view. Ma Hnin Wai Wai Aung, a company staff who is currently working in Laukkai responded to economic changes after the coup that “Laukkai is the only region that developed after the coup”. She told me in an interview that “the coup did not affect the economy of Laukkai”. Going overseas is not easy for basic-class people in Myanmar as training and visa fees may cost a lot but coming to Laukkai is much easier as they can work when they have connections there. Building and investment are developing but inflation rates can be the only thing that affects Laukkai after the coup.

However, after the coup of 2021, transnational crimes rose in Myanmar, especially from the SAR, a region not under the control of the regime. In border areas, not only Myanmar nationalists are trafficked but neighboring countries which challenge the national security of related countries. Among them, the Kokang criminal kingdom poses several challenges to Chinese national security interests (United State Institute of Peace, 2021).

In Kokang, illegal border crossing has increased after the Covid-19 breakout for casinos and other businesses. Online gambling and telecommunication give profits so that their leaders are protected Chinese illegal companies. At the same time, they also get taxes from their investments and companies. Armed organizations have bigger influences on the border which challenge the national security of China. Moreover, Chinese-related investments are also related to money laundering which come from big casino companies in the Kokang Region (United State Institute of Peace, 2021).

Conclusion

The economy of the Kokang region has had challenges due to unstable security because of the conflicts between the Tatmadaw and ethnic armed organizations. Despite the fact that the region has had economic development and Chinese companies’ investment, border security in the region is unsafe and named as one of the areas of high transnational crimes not only in Myanmar but also in Southeast Asia. Moreover, the Kokang region’s geographical significance for potential Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) projects has raised concerns about external pressures on Myanmar to implement development projects and infrastructures in the area. The Chinese government, particularly the Yunnan government, has expressed interest in leveraging the region’s strategic location to support its BRI. However, the region’s instability and ongoing conflicts have likely deterred meaningful progress in economic development and infrastructure projects. Under such circumstances, the potential benefits of being a part of the BRI must be balanced against the challenges posed by the prevailing security situation, evolving geopolitical situation, and developments in the Kokang region’s economy.

Bibliography

Hu & Konrad. (2017, April 28). In the Space between Exception and Integration: The Kokang Borderlands on the Periphery of China and Myanmar.

Irrawaddy, T. (2021, June 28). Myanmar Regime Locks Down Chinese Border Town Amid COVID-19 Spike. The Irrawaddy. https://www.irrawaddy.com/news/burma/myanmar-regime-locks-down-chinese-border-town-amid-covid-19-spike.html.

ISP Myanmar. (2023a, February 2). မြေအုတ်တို့ ပြိုလေရာ…“စစ်အာဏာသိမ်းမှုအကျိုးဆက် ဆုတ်ယုတ်မှု ခုနစ်ရပ်နှင့် လူ့အဖွဲ့အစည်းအတွက် မျှော်လင့်ချက် အလင်းတန်း.” https://ispmyanmar.com/community/insight-emails/ie-08/.

ISP Myanmar. (2023b, June 9). ထိပ်တိုက်တိုးမှုကို ရှောင်ခဲ့သည့် မိုင်းလားဆွေးနွေးပွဲ၊ စစ်ကိုင်းဖိုရမ်နှင့် ဖက်ဒရယ်ယူနစ်. https://ispmyanmar.com/community/insight-emails/ie-16/.

ISP Myanmar China Desk. (n.d.). မြန်မာ-တရုတ် နှစ်နိုင်ငံနယ်စပ် စီးပွားရေးပူးပေါင်းဆောင်ရွက်မှုဇုန်စီမံကိန်း(ချင်းရွှေဟော်-လင်ချမ်း နယ်စပ်စီးပွားရေးပူးပေါင်းဆောင်ရွက်မှုဇုန်). ISP Myanmar China Desk. Retrieved July 31, 2023, from https://ispmyanmarchinadesk.com/special_issue/cbez_csh/.

ISP Peace Desk. (n.d.). MNTJP/MNDAA. ISP Myanmar Peace Desk. Retrieved July 27, 2023, from https://ispmyanmarpeacedesk.com/eao/myanmar-national-truth-and-justice-party/.

Lintner, B. (2023, January 18). Kokang: Caught Between Myanmar and China. The Irrawaddy. https://www.irrawaddy.com/news/burma/kokang-caught-between-myanmar-and-china.html.

Lost Footsteps. (n.d.). Origin of the Kokang. 1600s – 19th Century Origin of the Kokang. Retrieved July 14, 2023, from https://lostfootsteps.org/en/history/origin-of-the-kokang.

Nanda. (2020, July 23). The Kokang casino dream. Frontier Myanmar. https://www.frontiermyanmar.net/en/the-kokang-casino-dream/.

Oo, K. (2023, March 8). Myanmar’s Spring Revolution Aided by Ethnic Kokang Armed Group. The Irrawaddy. https://www.irrawaddy.com/opinion/analysis/myanmars-spring-revolution-aided-by-ethnic-kokang-armed-group.html.

Three New China-Myanmar Cross-Border Trade Routes—ISP-Myanmar. (2023, January 13). https://www.ispmyanmar.com/three-new-china-myanmar-cross-border-trade-routes/.

Timothy Mclaughlin & Hnin Yadana Zaw. (2015, June 11). Under pressure from China, Kokang rebels declare Myanmar ceasefire | Reuters. https://www.reuters.com/article/us-myanmar-rebels-ceasefire-idUSKBN0OR0T120150611.

United State Institute of Peace. (2021, August 27). Myanmar Regional Crime Webs Enjoy Post-Coup Resurgence: The Kokang Story. United States Institute of Peace. https://www.usip.org/publications/2021/08/myanmar-regional-crime-webs-enjoy-post-coup-resurgence-kokang-story.

Xue Li. (2015, May 20). Can China Untangle the Kokang Knot in Myanmar? https://thediplomat.com/2015/05/can-china-untangle-the-kokang-knot-in-myanmar/.

ကိုးကန့်ကိုယ်ပိုင်အုပ်ချုပ်ခွင့်ရဒေသ လောက်ကိုင်မြို့နယ်၊ (2019, September 30). လောက်ကိုင်မြို့နယ်ဒေသဆိုင်ရာ အချက်အလက်များ၊ မြို့နယ်အထွေထွေအုပ်ချုပ်ရေး ဦးစီးဌာန။.