Abstract

This study examines the emergence and evolution of Myanmar’s Independent Cinema as a unique platform for creative freedom. A series of interviews with Myanmar independent film industry professionals led to the development of this research, mainly exploring the challenges filmmakers face and how their work has given voice to marginalized groups in Myanmar.

Introduction

The limitations of political constraints and social norms have continually challenged Myanmar’s artistic endeavors for decades. A celebration of Myanmar Cinema’s centenary in 2020 provided an opportunity to reflect on its history, one that has not always been glorious, largely due to isolation and propaganda. Nevertheless, significant changes in independent filmmaking in Myanmar have materialized in the past few decades.

The definition of the “voice of freedom” was defined according to A, a filmmaker from Myanmar as

“The right to create what one wants, to tell what one wants without restrictions of any kind.”

Whether Indie films can achieve this has become an area to explore. To what extent the creators of indie films can express their voices is also a factor that must be considered.

Historical Background

The independent film industry in Myanmar is relatively young, having undergone substantial growth in the past decade. A significant part of this growth can be attributed to the emergence of unique and uncompromising cinematic voices that are challenging conventional norms.

The heart of this research lies in the interviews conducted with professionals from Myanmar’s Independent film industry. It’s clear from these interviews that independent films have become a powerful medium for marginalized voices, the voices of young people, women, and the LGBTQ community who have been historically overlooked or silenced by mainstream media.

The 5 interviewees spoken with acknowledged the importance of documentaries. Two of these are primarily active in the documentary field. The first critically acclaimed documentary movie from Myanmar is said to be “A Million Threads’, produced in 2008. According to the interviewees of this research, it was confirmed that the line between Indie movies and mainstream media fades when Indie Filmmakers have achieved success and recognition from the public. In many countries, the independent movie industry acts as a medium before showing the movies of new directors in mainstream media such as movie theaters.

An unfinished story of Myanmar new wave Cinema

This research conducted interviews with 5 professionals from the Myanmar Independent film Industry. Interview questions were designed to discover oral histories from these professionals, including their visions, their art, and their expectations and ideas related to the film industry in Myanmar. I aim to answer the question, ‘Do Myanmar Indie films represent a voice of freedom for its creators, and if so, in what ways does this occur?’ Their films appeared apart from the restrictions; strict censorship, political situations, social norms, and self-censors.

According to the interview data, indie films represent the voices of young people, women, LGBTQ and other voices left out in the past. The Indie films started to touch on several issues that are neglected or intentionally shielded from being shown to the public. The marginalized voices are also found in Indie films.

I conducted a total of five interviews where I met with the filmmakers and other professionals from the film industry to discuss these topics. The age range of interviewees was from 25 to 54. Most came from different backgrounds before entering the film industry. The passion for telling stories through moving images, however, connected all of them. Nyi, the editor of nearly 50 indie films, told me:

“For me, Indie is a wave, a breakthrough. Commercial cinema has to rely on money and the audience. The income makes the success. Indie asks for aesthetics and has a free voice, we can create the things that we want to.”

Indie Filmmaking in Myanmar; Challenges

K, a cinematographer based in Yangon briefly explained how Indie filmmakers are able to express themselves more freely:

“I don’t get to shoot some places that they have restricted such as government places. But we are skillful enough to think about how to break free as we have been trained to live under military control. We have never been free. The freedom of making films means I want people to create films free from barriers and restrictions.”

According to the interviewees, independent filmmakers in Myanmar have blurred the lines between their work and mainstream media. Their success has transcended the independent realm, aligning with the global practice of independent cinema and serving as a stepping stone for emerging filmmakers. K added:

“I only think of the ethics of the filmmaker and not by the control of the censors. I had to free my mind from propaganda and social norms, gender issues, and misconceptions from the mainstream that discriminate between reality.”

The filmmakers in Myanmar have to withstand ridiculous situations and obey rules that make no sense at all. According to an article on Censorship in Myanmar, the director of a horror movie said that he had to add more scenes to show the plot where the spirit has been freed and gone to heaven because Buddhists believe that ghosts and spirits must always be accessible at the end. In a similar vein, the interpretation of soldiers must always be admirable and hero-like in all mainstream movies in Myanmar.

Case study, The Monk (2014)

The first Indie film that tried to break the redundancies was “The Monk” (2014) by director The Maw Naing.

Zawana, a young novice who was having dilemmas about whether to keep living as a monk or quit, is portrayed in the film as a realistic demonstration of the monks in reality. The village, the daily life of a monk, and how we define a “real” monk have been shown by metaphors, dream life sequences of its cinematography, and brilliant screenwriting.

Most Indie films cast non-actors and background actors who have talent and a love for Cinema. On the other hand, the casting of inexperienced actors has both advantages and downsides. In my view, the film The Monk might have been more appreciated if it were not for some of the awkward dialogue.

In making an Indie film, all the technicians have to collaborate. There is not only one leader. Most of the Indie films are low-budget and short of staff. One technician has to be two or three professionals such as a song recording artist may also work as a sound engineer and sound producer for the film.

Case Study 2. Three Strangers (2022)

The representation of queer people in Myanmar Cinema was not so glamorous. In most movies, queer characters are often portrayed as laughing stocks or simply as living in a wrong way. One article claimed that censorship has restricted that if a film shows a homosexual person, he or she must be ‘enlightened’ and go back to a “normal” heterosexual person at the end of the film. The community of queer people in Myanmar have experienced hardships because of misconceptions such as these depicted in the big screen.

The indie documentary Three Strangers shows a family of three with a transgender father, mother, and their adopted son in a faraway village, away from cities in the northern Rakhine State. The film consists of interviews and narration of how a family of difference has formed and lived every day.

About the film, K, the cinematographer of the film said:

“We had to go to the village where they live five times in 4 to 5 years. The production took another 3 years to finish. So, around 8 years had been spent in making this film happen.”

The film will simply age with the audience as the boy grows old peacefully in a loving house. Unlike from the representation of queer people in most mainstream media, the film did not force the audience to admire them or overly dramatize the hardships of queer people in poverty in a faraway land. After all, the film is intended to be one about love.

Freedom to what extent and what to break next

We have only scratched the surface of what we really want. A female filmmaker in Myanmar, N, said that she has had to overcome many obstacles in her quest to make short films. These barriers are not only tangible but appear often in internal conflicts between individuals as well. The 25-year-old filmmaker said:

“I believe we have our filters, and censors in our minds as Burmese women. Such as writing about a cheating woman character. I have recurring thoughts that I don’t want my character to be seen like that etc. Even directing a smoking scene makes me hesitate.

I think it’s because of how we have been brought up in this society and the things that influence us in bringing our visions to big screens. I think it’s because I’m a girl. I know I don’t need to care about others’ opinions but I can’t help but still partly care, such as directing intimate scenes, etc.”

Amid the country’s flash political changes, N was in a state of total desperation. There were many resistance acts against the coup by most of the citizens. The university students in Myanmar decided to join the civil disobedience movement along with other professionals from Myanmar who stood up against the coup. In the coming months, the lives of the students differed according to their choices as some of them decided to go back to college and continue their studies. The students in the resistance forces were in a big dilemma of whether to go back to their studies or continue the act of resistance.

N collected some of those students who were originally from an art school and started a workshop with them. The workshop appeared to become consistent and N and her colleagues were able to produce four of the workshop participants’ short films. A, a 33-year-old filmmaker commented:

“These are not political films but a true representation of what we have to encounter every day living here.”

“No” Censorship movement

Young people in Myanmar were against unqualified Mainstream movies, and starting to search for a new taste. After a prolonged period of watching unqualified movies with over-acting and repetitive storylines, audiences wanted something fresh. They wanted to feel a genuine touch of aesthetics that flavors the dedication and free spirit of a newly changed nation.

There was a “No Censorship” movement with the initial purpose of turning the tables of movie censorship into an audience rating system in 2019. Nearly everyone involved in the film industry has acknowledged the movement and supported it. A new batch of young and brave directors such as Na Gyi, Christina Kyi, Htoo Paing Zaw Oo, etc. emerged. Nya (2018) is claimed to be an Indie film because of the cast who were eager, young, and inexperienced.

Cultural Revolution

N, the editor asked the audience:

“But we talk Burmese so it’s a Burmese film for sure? Don’t we need to show, not tell?”

In making an Indie film, producing “Burmese” films that reflect the real conditions of Burmese people always comes first.

As a result of the advent of cinema, many attempts have been made to document the daily lives and culture of faraway ethnic groups. K said:

“I want to capture the real culture left as much as possible before they disappear completely. You know, when we travel for the first time to a place and when we get there again several years later, I can see the traditions are fading away slowly. I want people to notice that.”

The Indie films touched on sensitive issues such as religion, and the act of revolution favoring the voices of oppressed groups. They also contain the languages of Ethnic people and how they communicate in daily life.

Success and Recognizations

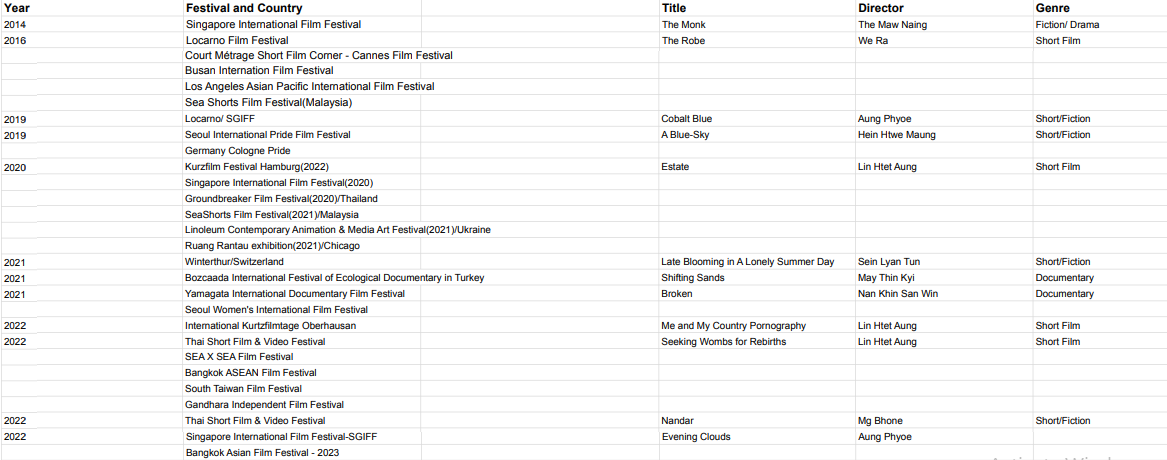

Myanmar Indie films have been recognized and praised by a variety of international film festivals since the previous decade. Table 1 shows some of the festivals that screened and nominated Myanmar independent films in this time.

Several independent film festivals have been held in Myanmar in the past decade. In 2012, the Wathann Film Festival was founded. There were many opportunities for aspiring filmmakers to showcase their work in festivals in Myanmar including Memory! Film Festival and Freedom Film Festival in Myanmar.

Conclusion

In conclusion, Myanmar Independent Cinema has played a pivotal role in providing a platform for creative freedom within a challenging sociopolitical context. This research primarily relies on interviews and primary sources, underscoring the significance of these voices in promoting artistic expression in Myanmar.

Upon analyzing the discussions of both the filmmaker and the audience, it is clear that Myanmar has rare opportunity to learn about filmmaking and how it is done. Nevertheless, the interviewees and their teams are already filling up that gap by founding magazines for films, contributing back to society through the mobile cinema of Indie films, and establishing free workshops and events where like-minded individuals with a love for cinema can benefit.

A new generation of filmmakers from Myanmar are dreaming of a big future ahead despite the uncertain political conditions. A, a 33-year-old filmmaker stated: “We all dream of a day when we can show our films without any fears, just excitement and freedom in our mind.”

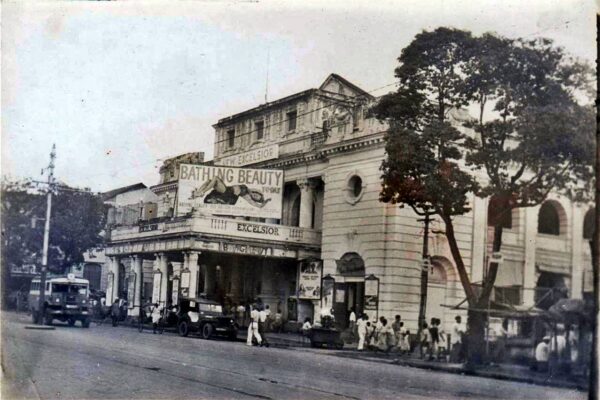

Figure 2: Wazira cinema today, captured by P.K.N. on September 21, 2023.

Acknowledgments

This research would not have been possible without the participation of professionals in the Myanmar independent film industry who contributed invaluable insight.

References

Shin K. P. (2017). Myanmar Filmmaking Today: At Transitions in Business and Politics. Asia Center Japan Foundation. Accessed 20 Sept 2023. Available at: https://jfac.jp/en/culture/features/asiahundreds023/

Myanmar Motion Picture Organization (2016). The History of Myanmar’s Films (Golden Age) 1946–1970. Yangon: Myanmar Motion Picture Organization.

History of Burma. [n.d.]. The cinemas that I miss. Myanmar Photo Archive. Accessed 20 Sept 2023. Available at: https://www.myanmarphotoarchive.org/the-cinemas-that-i-miss/