This paper sets out to consider the legacy of a silenced colonialism in Italian society, starting from the quite dissimulation of the events themselves and their convenient exclusion from historiography to the construction of self-serving myths of exceptionalism setting Italian colonialism apart from the rest. The figure of anti-colonial scholar Angelo Del Boca and his research on the topic of Italian colonial war crimes will be taken as explanatory reference in order to analyse the antagonizing attitude adopted by the academic world towards postcolonial research, as well as to emphasize the necessity of a large public debate on the topic. Lastly, a consideration of the consequences of the paradigms of fascist colonialism on contemporary Italy will be undertaken to highlight how the refusal to accept the severity of the crimes committed in the past still affects the way Italians understand their own identity and their relationship with the Other.

Brief introduction to Italian colonialism

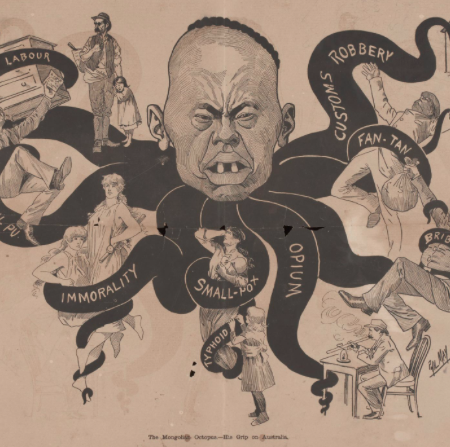

The conquest of colonial territories was practiced by all western European nations. For some, the imperialist control of other lands lasted centuries, while others emulated them by rushing to get a single piece of land to claim as theirs. Italy joined the struggle for Africa of the 1880s relatively late and with comparatively few results, only seizing territories in Eritrea and Somalia. After all, as a newly unified nation state, Italy had taken part to the scramble mainly to prove to the rest of Europe that Italy, too, was able to subjugate those who were deemed weaker populations in order to be included into the inner circle of European imperialist powers. However, the kingdom of Italy’s dreams of glory were met with a harsh defeat in Ethiopia, especially during the battle of Adua of 1896. After this first phase of liberal colonialism, the colonial impetus in Africa resurfaced in the 1930s, complemented by a new approach to the concept of colonialism: establishing colonies meant creating an empire, which in the fascists leaders’ illusions of power could lift Italy to the top of the European power pyramid, when until then it had only found itself at the bottom, mocked and ridiculed. Mussolini took advantage of the resentment left after the defeat of Adua and the discontent for not having been considered as an equal during negotiations of the first postwar period to incite a newfound colonial spirit, promising to provide Italians with a posto al sole, a place under the sun. By externalizing internal problems and deceiving the population through the classically fascist rhetoric of grandeur, he managed to gain support for his deadly campaign of conquest. Deemed anachronistic even at a the time, when European-occupied territories were entering a phase of decolonisation, the fascist regime was instead unswervingly set on embarking upon the African campaign.

The hidden truths of the Ethiopian campaign

This Ethiopian enterprise was subsequently obscured in Italian historiography. In fact, the colonial experience of fascist Italy and the violence it perpetuated have been silenced from public discourse and omitted from collective memory in alignment with policies of self-absolution during the post war period. Angelo Del Boca, a pioneer of Italian colonial studies, was one of the first scholars who embarked on a process of uncovering of repressed war crimes. A former resistance fighter, Del Boca opposed the fascist regime even during its heyday, and he continued to campaign for the recognition of the regime’s faults even after its formal end, when the political climate in Italy was precariously balanced and everyone – above all the political leaders – generally preferred to look to the future instead of coming to terms with an uncomfortable past. In this situation, as the process of general amnesia was silently but surely catching on, Del Boca initiated a project of retrieval of sources regarding the colonies. From his research, we know that Mussolini already in 1926, then minister of war, had plans to invade Ethiopia, but concluded that Italy wasn’t yet ready to sustain the economic toll this venture would entail. Only in 1935 did Italy invade Ethiopia, inaugurating the so-called Campagna d’Etiopia. Mussolini decided to undertake a campaign of chloroformisation of the adversary (cloroformizzazione dell’avversario)[1] , personally pushing for the adoption of harsh measures in order to deal with adversaries, depicted as mere animals, sometimes as game from a hunt[2]. The proof of the Duce’s personal involvement in the process of decision making regarding the actions of the Ethiopian war is represented by a series of telegrams he exchanged with his appointed officials and generals. In these sources, Mussolini’s ruthlessness is detectable, especially in his peremptory orders of when to deploy toxic gasses. After the first world war, the Geneva Convention – which Italy had also signed – declared some of the gasses used in chemical warfare banned: yperite gas, known also as mustard gas, was among them. Violating this internationally agreed regulation did not worry Mussolini in the slightest: several telegrams, in fact, consist in his direct orders to deploy yperite gas on the ill-equipped Ethiopian population in order to continue on with a policy of terror.[3] Evaluating the international equilibrium of power and consent for deciding when best to attack was pivotal[4], when news of the usage of chemical warfare spread, reaching even Geneva, and denial of any misdeed became the official stance presented by the Italian government.[5] Despite international disapproval, Mussolini continued undeterred to grant his authorization to utilize all war measures on every scale – even pondering the possibility of initiating bacteriological warfare[6], a recently developed military strategy that probably would have caused even more disastrous consequences if his officials did not dissuade him, only managing to do so by pointing out how this action would draw undisputable negative reactions from the rest of the world.

Evidence of the usage of chemical weapons can also be found in sources from the other side of the conflict: the Ethiopian emperor Hailé Selassié, in a speech to the League of Nations – of which both Ethiopia and Italy were members – denounced the criminal use of gas, whose effects on the population were devastating. The corrosive action of the gas on the skin caused almost immediate death on whoever happened to be touched by the thin rain of yperite. Moreover, many victims were counted also among civilians because of the poisoning of water supplies and arable lands caused by aerial bombings. For the Ethiopian population, the two-year period of 1935-36 was marked by extreme sufferings, the strife of war being exacerbated by the unrelenting gas bombings. In one of his testimonies, the emperor himself discloses that the bodies were so many their numbers exceeded the living, so that a proper burial would not have been possible.[7] The reason behind the continuous bombing of the adversary, on the part of the Italian side, was to conduct the invasion as swiftly and as aggressively as possible in order to keep the enemy from organizing a proper counteroffensive and therefore obstruct the occupation of the capital of Addis Ababa, one of the key objectives of the entire African campaign. However, the atrocities did not end after the takeover, as an order from the Duce himself reiterates four times that everyone found in possession of weapons in the capital must be executed by firing squad[8], in proper fashion of fascist squadrons. The behaviour of the Italian side did not reflect fascist violent modus operandi only in actions but, of course, in ideology too. In fact, Del Boca argued, that among Mussolini reasons for initiating the Ethiopian campaign, one was to test the making of the ‘new Italian’[9], i.e., if the cultural reimagining of the fascist regime had taken root among Italians. Under this outlook, war was seen as an opportunity to bolster the “honour” of the “true man”. The famous journalist Indro Montanelli, who at the time came to Ethiopia as a volunteer soldier, wrote that “This war is like a grand holiday, given to us by the Gran Babbo (i.e., Great Father) as a prize after thirteen years of school. And – just between us – it was time”[10]. Montanelli represents then the perfect product of the workings of fascist ideology on the minds of men looking for glory. Even though, in his later years, he claimed to have rejected the undeniably fascist origins of many of his previous ideals, he continued to defend his participation in the colonial war.

Del Boca and the struggle against revisionism

Despite the extensive research conducted by Del Boca on the topic of Italian war crimes in Ethiopia, his claims were progressively dismissed by the academic world. He was also continuously harassed and threatened by the right-wing press, accused of being unpatriotic by spreading what were considered lies. In the meantime, Del Boca also reported the difficulties he encountered in accessing primary sources regarding the colonial period because of the monopoly held on them by the Committee for the documentation of the Italian endeavour in Africa, which in 1952 was tasked with organizing the documentation regarding the colonial period. Almost all members being former officials of the Ministry of Italian Africa, the committee represented then a veritable colonialist lobby: the compilation of forty volumes born out of their work (L’Italia in Africa) was, of course, filled with historical distortions[11] and aimed at protecting the interests of its own editors. Being then the appointed custodians of documents of the period, the Committee essentially promoted the repression of colonial faults by obstructing the access to state archives to anticolonial historians such as Del Boca for decades.[12] As recounted by Del Boca himself, scholars holding more progressive stances were denied access even until the late 1970s, making it even more difficult to uncover what really happened during the African campaign. This lack of free access to sources inevitably contributed to the overall dissimulation of past wrongdoings, which were either relegated to the realm of forgotten memories or mystified and represented as glorified exploits, thus fomenting the creation of the myth of the ‘Italians good people’ (Italiani brava gente), a self-gratifying lens through which all memories of the African war would be interpreted. The distorted narrative promoted by the romanticization of the Italian presence in Africa whitewashed all faults and crimes Italians were guilty of, maintaining that actually, Italians were a good-natured people who came to Africa with the only aim of helping locals build roads and modern infrastructure, in an effort of helping them become civilised. A latently racist and patronising outlook, that is actually a front put up to cover for far more vicious actions. This denial of faults resisted also thanks to front row actors in the colonial war like the previously cited Montanelli and many other war veterans still holding it in high regard.

While the right-wing press and the colonialist lobby had been raging against him[13] since the publication of his first book on the topic, La guerra d’Abissinia (1965), Del Boca indeed claims that high profile individuals personally antagonized him, first among them the former minister of Italian Africa, Alessandro Lessona, and one of the most famous journalists of the postwar period, Indro Montanelli. Lessona is regarded as the theorist of Italy’s belated – but nonetheless ruthless – imperialism. At first, he affirmed that Mussolini issued the command to use the gas only once, answering a request posed to him by general Graziani, and that the consequences of the bombing was not really as disastrous as claimed by Del Boca. Then, in 1980, he reticently admitted that asphyxiant gasses were used more than once, only to retract his statement five years later, when confronted directly by Del Boca on live television. Continuous contradictions and diversions were then the standard response to irrefutable sources like Mussolini’s own words and clear orders present in his telegrams, some of which recited by Del Boca on that same tv program, in front of a tongue-tied Lessona.[14] Still, a vocal admission of responsibility was never properly acknowledged by the former minister. The other great opponent to Del Boca’s claims was indeed Indro Montanelli, a former colonial soldier with less material responsibility than Lessona, who remained nonetheless a fervent admirer of Mussolini and a supporter of the colonial endeavour. In fact, he continued to uphold the value of the colonial enterprise, of which he had a romanticized view, claiming that the Italian soldier was more tolerant and that “Our colonialism was the most human among all […]as demonstrated by the memories that Ethiopians themselves have of Italians”[15], a statement that represents a perfect re-proposition of the previously mentioned myth of Italiani brava gente. It is difficult to understand how the journalist could claim to have been positively regarded by the population he contributed to colonize, given also the fact that he was one among many Italian men to take advantage of the Madamato, the practice of taking young local girls as ‘temporary wives’ for the time of the soldier’s permanence in the colony. When confronted with accusations of rape many years later, Montanelli still found nothing wrong with his marriage to his twelve-year-old child bride, whom he remembered as a “docile little animal”[16].

Notwithstanding the personal allegations, as the years passed, Montanelli as an historian began to recognize the anachronistic character of the Italian colonial endeavour, while also nostalgically recalling his military experience in the colonies, a rather ambivalent stance on the matter. On his appointed column in the newspaper Corriere della Sera, of which he has been one of the most influential contributors, he cited his authority as an eyewitness to fervently declare that the claim of the usage of gas bombings was false: he did not have any direct experience of the bombings, so he concluded they did not happen at all. When presented with proof by Del Boca, he turned to avoidance, ignoring the latter author.[17] After many decades of denial, his doubt arose, and he entailed a discussion with Del Boca on the same newspaper in 1995. Their exchange came to prominence, catching the interest of the general public. It was the first time a public discussion on the matter of Italian colonialism was held on a larger, national scale. This nation-wide attention reached even the Parliament, and Del Boca seized the opportunity by requesting, together with other historians, that the government officially disclose all documents relative to the period in question and make them accessible for all scholars.[18] A parliamentary inquiry was then launched on the topic of the gas: Del Boca was finally able to prove his life’s work true on a wider, public stage after thirty years of harassment and denial when the government admitted – albeit reticently – that the gas was indeed used systematically. Montanelli found himself forced by the circumstances to admit he was wrong, too, famously headlining his dedicated section of the Corriere della Sera “Gas in Ethiopia: the documents prove me wrong”.

Postcoloniality, memory and populism

As showcased in the previous sections, Italian colonialism, unlike for other overseas empires, appeared not to affect the metropole. Most of all because Italian colonial territories did not undergo a process of armed decolonisation such as in other parts of Africa under French or British rule, given the fact that Italy was stripped of its colonies by the UN after the end of the second world war. This peculiar context created in Italy a climate of ‘indirect postcoloniality’[19], where the presence of immigrants coming from colonised territories was not as notable as in other European countries because no consistent migration flow from the colonies to the motherland took place. For this reason, with no direct evidence of its colonial past to account for at home, Italy implicitly decided to turn a blind eye to the events of the African campaign: if before news of the violence in the colonies came to Italy only though the positive lens of propaganda due to fascist censorship, even in the postwar period, when a process of uncovering could be possible thanks to the fall of the regime, everything was instead conveniently swept under the rug. The newly established Italian republic had of course many issues to deal with –an extremely ideologically divided country having to bear the weight of post war reconstructions, the governments of the immediate post war period had to juggle internal consensus and external tensions to maintain their legitimacy and provide a future for a country freshly coming out of two decades of dictatorship. So forgetting was deemed the easiest option: no public debates, no trials, no acknowledgement of accountability – and not just for the faults of the colonial endeavour – all in the name of a brighter future rising from the ashes of the past. But is a future like that possible without taking into account what Italy was in the past? Or better, by only relying on glorified accounts of its distant history like the times of ancient Rome or the Renaissance, with just a side mention of the horrors its recent history produced?

If this convenient amnesia was partly a conscious choice at first, over the years it ended up becoming an integral part of the identity of the Italian citizen, resulting in behaviours and stereotypes from the fascist period having been passed down almost unchanged for generations, because Mussolini did indeed succeed in reshaping the conformation of the new Italian man. Many of his ideological values based on the cult of violence, traditionalism, obedience and machismo still permeate contemporary Italian society, a result of a process of ‘de-fascistization of fascism’[20], a minimization of the inherent violence and white supremacy of fascism promoted by the post fascist ruling elites with the purpose of avoiding their own liabilities from their involvement in the fascist regime, which also seeped down to the rest of the population thanks to the assent of the public media.

Applying this paradigm to the colonial past, it is possible to say that the simplistic dismissal of these events ended up leaving unprocessed faults unrecognized, with behaviours constructed through fascist propaganda still having a hand in defining the concept of ‘Italianness’ as opposed to the identity of the ‘Other’ that, at the time, was to be identified as a colonized other. The way Italians think of themselves in relation to what is perceived as alien – what is or is not included in the murky definition of Italianness – can be traced back to the refusal to deal with a violent and criminal legacy, and to accept the severity of the crimes committed. Nowadays, when encounters with the perceived Other are more common, this convenient gap in memory passed on generation to generation has resurfaced in the adoption of the same oppositional attitude of self-gratifying myths and accusative stereotypes which had been created to perpetuate the colonial narrative of fascist times. This inherited narrative has been reshaped and readapted to today’s populist rhetoric, leading to opportunistic manipulations of the past. As stated by Proglio[21], populist narratives retrieve colonial representations that were never properly deconstructed, and now endure instead with new targets: the migrants coming from the Mediterranean, the new racialized other. Narratives about migration are therefore instrumentalized to serve a wider populist rhetoric based on the othering of what is considered alien to the authentic Italian identity, as a perfect example of contemporary anti-immigration populist propaganda. The survival of the racist colonial imaginary can then be identified as the origin for the rampant anti-immigration sentiment that has been dominating Italian politics in recent years. The re-appropriation of colonial memory, and a widespread, collective recognition of responsibility is therefore essential, and it could represent one of the most important starting points for Italy’s necessary but still lacking redefinition of its identity as a postcolonial society.

[1] Del Boca, Italiani, brava gente?, 193

[2] Del Boca, Italiani, brava gente?, 197

[3] Mussolini, telegram n° 8103 to Graziani

[4] Mussolini, telegram n° 180 to Badoglio

[5] Del Boca, I Gas di Mussolini, 56

[6] Mussolini, telegram n° 2053 to Badoglio

[7] Hailé Selassié quoted in Del Boca, I Gas di Mussolini, 58

[8] Mussolini, telegram n°5007 to Badoglio

[9] Del Boca, Italiani, brava gente?, 196

[10] Montanelli, XX Battaglione eritreo, quoted in Del Boca, Italiani, brava gente?, 199

[11] Morone, La fine del colonialismo Italiano tra storia e memoria

[12] Del Boca, I Gas di Mussolini, 204

[13] Del Boca, I Gas di Mussolini, 150

[14] Del Boca, I Gas di Mussolini, 158

[15] Montanelli, Etiopia: colonialismo all’Italiana, Corriere della Sera, 1995

[16] Montanelli on the TV program L’ora della verità, 1972

[17] Del Boca, I Gas di Mussolini, 160

[18] Fiori, Corriere della Sera, 1995

[19] Lombardi-Diop, Postcolonial Italy, 4

[20] Gentile quoted in Lombardi-Diop, Postcolonial Italy, 92

[21] Proglio in De Cesari, Kaya, European memory in populism, 113

Bibliography

De Cesari, Chiara, and Kaya, Ayhan. European Memory in Populism: Representations of Self and Other. Routledge, 2019.

Del Boca, Angelo. I Gas Di Mussolini: Il Fascismo e La Guerra d’Etiopia. Editori Riuniti, 2007.

Del Boca, Angelo. Italiani, Brava Gente? Neri Pozza Editore, 2008.

Fiori, Cinzia. “Gas Italiani in Etiopia? Ora un generale dice di si”, Corriere della Sera, 1995.

Lombardi-Diop, Cristina. Postcolonial Italy: Challenging National Homogeneity. Springer, 2012.

Montanelli, Indro. “Etiopia: colonialismo all’Italiana”, Corriere della Sera, 1995.

Morone, Antonio Maria. “La Fine Del Colonialismo Italiano Tra Storia e Memoria.” Storicamente 12 (July 11, 2016). https://doi.org/10.12977/stor623.

Telegrams from Benito Mussolini to Pietro Badoglio. Ministero delle colonie. 1935-1936.

Telegrams from Benito Mussolini to Rudolfo Graziani. Ministero delle colonie. 1935-1936.