War in Northern Uganda (1980s-2008) and its impact on the youth in Gulu district.

Background

Since gaining independence from British colonial control, Uganda has seen a turbulent political history marked by dictatorships, disputed election results, civil wars, and an invasion by military forces. There is much discussion to be made on the degree to which these crises weakened the state and the degree to which they were triggered by a weak state. From 1962 until 1986, Uganda experienced a crippling civil conflict that brought the country to the brink of total collapse and resulted in eight changes of leadership, five of which were violent and unconstitutional. Fast-moving reconstruction has been taking place in the nation since 1986.

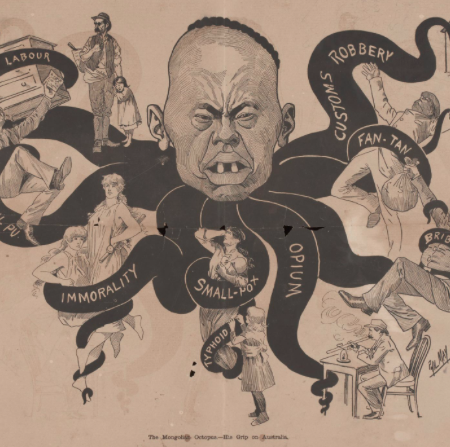

The repeated outbreaks of political violence and state breakdown in Uganda are caused by a number of variables. Some have internal causes, while others have connections to outside influences. ‘Legacy of colonialism’ is a term that can be used to explain internally generated issues. Colonialism had profound effects on Uganda’s society, economy, and politics. It left the nation with a bad legacy of racial conflict, uneven development, elite polarization, a limited economic base, and feeble state machinery. Instead of reversing this damaging legacy, postcolonial leaders have, for the most part, made it worse by stoking more ethnic conflict and division, taking a rigid stance on matters of national significance, marginalizing or attempting to marginalize entire regions and ethnic groups, implementing disastrous economic policies, and further weakening an already frail state apparatus.

By 1985, with the war going badly for the UNAL, resentment built up among both Acholi foot soldiers and officers. For they not only bore much of the brunt of the most difficult fights including the New Western Uganda front, but were also singled out for blame by the other side, despite not usually being in charge of policy or strategy. President Obote was overthrown in July 1985 by some of the Acholi officers, after which one of the leaders of the coup, Tito Okello, assumed the presidency. The new military rulers were unprepared and unqualified to run the government and were rebuffed in their attempts to make peace with NRA and bring them into the governing coalitions.

As Sverker Finnstrom points out, however, the end of the bush war was not an end to the war in Uganda. Instead, the 1986 capture of Kampala marked the starting point of several new conflicts in Uganda. Museveni’s army persuaded fleeing former government soldiers north and soon began committing human rights violations of its own; abducting, beating, raping, and killing civilians and former soldiers alike. They also stole and destroyed Acholi properties including hundreds of thousands of cattle and allowed cattle keepers from the east of Acholi to steal even more.

Since 1986, an armed conflict had been raging in the north of Uganda. The Lord’s Resistance Army (LRA), an armed opposition group driven by its messianic religious leader Joseph Kony, has been trying to topple the government, impose a system based on the Ten Commandments of the Bible, and end the marginalization of the Acholi community. Two million people have been forcibly displaced as a result of violence against the civilian population, the kidnapping of thousands of youths to expand the ranks of the armed group, and clashes between it and the armed forces. When the Sudanese government permitted the Ugandan armed forces into its territory to pursue the organization in 2002, the LRA continued to expand its operations into southern Sudan. This sparked an uptick in violence and the conflict’s expansion into this region.

Therefore, the main objectives of this study will be to analyze War in Northern Uganda (1980s-2008) and its impact on the youth in the Gulu district.

The war and the population

The literature herein relates to the civil war in northern Uganda, which lasted from 1986 to 2006. It describes how Gulu, despite being a center of internal displacement with over 130,000 people crowded into a space meant for a quarter of that number, remained an island of relative security amidst the violence that wracked the rest of Acholi land (Royo, n.d.). Therefore, it describes how Gulu was mostly isolated from the massive devastation in the countryside and remained safe, even at night. However, leaving town meant entering a zone of unpredictable violence, where tens of thousands were killed and abducted, and waves of humanitarian crises left perhaps over 100,000 civilians dead. It was also worth noting that youth, like in many of today’s ‘dirty wars’, was the primary target of the extreme violence by both the Lord’s Resistance Army (LRA) rebels and the Ugandan military alike. Despite being a center of internal displacement, Gulu was spared in large part the internal conflict and upheaval that often characterize such scenes of massive displacement and deprivation.

According to the United Nations, the LRA was in charge of more than 100,000 fatalities, 60,000-100,000 kidnappings of youth, and up to 2.5 million civilian evictions between 1987 and 2012. While kidnapped women and girls typically end up as the wives of LRA leaders, where they endure repeated rapes and sexual assaults, the group frequently coerced youth to kill or injure their own relatives.

Despite a sharp drop in LRA fighters since 2012, the organization still poses a threat to people in Central Africa. To sustain its operations, the LRA has taken advantage of a lack of regional and international presence in isolated regions of eastern CAR and northeastern DRC.

The literature in this passage discusses the potential risk to Gulu’s stability from internal displacement following the end of the fighting in northern Uganda. The passage notes that during the war, Gulu remained relatively stable despite being a center of internal displacement. However, the social conditions in Gulu have worsened since the war, with slums expanding and a new population of young and extremely poor individuals who are landless and without hope of employment. The passage suggests that this group is disproportionately marginalized and excluded from Acholi society, which could lead to future civic conflict as poverty worsens and disparities of wealth increase.

The war and its memories

The past made present, according to Michael Rothberg’s interpretation of Richard Terdiman’s definition of memory. According to his theory, memory is a “contemporary phenomenon,” something that, although concerned with the past, occurs in the present through work or action (Radstone 2020). However, in Northern Uganda, a countermove to the prevailing method of memory-making, consisting of subversion of native modes of memorialization, shapes the present. In top-down commemorations made feasible by strategic appropriation and resignification, this dissidence enables local actors to challenge the established hierarchy of principles and values. Werbner responds by noting that “memory as public activity is increasingly in peril” in postcolonial Africa (1998: 1).

The stories told by the site highlight the importance of local histories in northern Uganda, and they constantly rehearse diverse narratives of the violent past that unfolded over time and its divisive nature among members of different clans who had known each other as neighbors.

Many people have very bad memories, they saw people get hacked, chopped and some put in pots and cooked by the rebels. The people are angry with the rebels who wreaked havoc on the land for more than two decades.

Because the violence split families, especially when youth were dispatched to kill their families or members of neighboring clans, members of the same family may have distinct recollections and traumas of the war. The guide also mentioned young girls who were forcibly dragged into the bush to become child mothers during the war and had images of the violence they endured (Baines 2017). As a result, the Memorial Centre serves as a repository for these horrific occurrences, which are repeated and framed by the language, as well as the gendered and local cultural context of the conflict (ibid). The Centre offers pathways for individual memories to travel in order to become part of the collective tale of the past told about the war (Erll 2011: 11). For example, stories as such are many from the region:

“Go look for your people, in this part of the country, if a woman comes home with a child whose father is unknown, her brother takes up the child as his own, but it seems different with youth born in captivity. They are rejected by the mother’s family. Normally, girls who return from the bush can inherit their father’s property but for these youth, their paternity is not known so they have no right to inheritance (ibid).”

Surprisingly the Ugandan government never hard any special interventions for this group of youth, many of whom have outgrown the legal age to be considered youth according to Frank Mugabi, the spokesperson for the Ministry of Women, Labor, and Social Development, under whose purview such youth would belong. Everyone beyond the age of 18 is no longer considered a kid in Uganda. For example, Atimotek was born in a Lord’s Resistance Army (LRA) camp either in northern Uganda or South Sudan. Her mother was abducted as a young girl from Kitgum district by the rebels and forced into marriage with a teenage rebel. Atimotek learned how to survive on one meal a day: running barefoot for long distances, sleeping in the cold, and shooting a gun (Mwambari 2021).

Atimotek’s life only got worse after they left the bush since her mother died, leaving her and her three brothers to face the world alone. She has had to perform part-time work in a salon, earning Ush 2,000 ($0.5) per head, or wash people’s clothes and weed their gardens. She has sought food and educational possibilities through various organizations, all while battling stigma from a society that considers them as “children of the rebels.”

Why the LRA violence involved youth

This is one of the major interests of many studies to look at how the LRA indoctrinates youth outside of northern Uganda, where fresh recruits no longer share the same cultural background or language as long-term troops. Most findings add to the growing body of research on the methods through which youth are indoctrinated into violent organizations. To fill its ranks, the LRA has depended primarily on forced recruiting and youth abduction, and it has developed methods for cutting ties with civilian life and nurturing new identity creation. Understanding the processes that lead to this, especially when the group spreads into areas with no linguistic or cultural ties to the long-term combatants, provides a rare glimpse into methods of indoctrination and psychological control for youth linked with armed groups (Kelly, Branham, and Decker 2016).

According to Kelly, kidnappings often occurred as part of a larger attack on a village. Interviewees described a preference by the LRA to take children and youth, rather than adults because children are easier to control. They also noted that both boys and girls were vulnerable to being taken.

For a variety of reasons, Kony’s reliance on kidnapped children has allowed him to maintain his internal grip on the LRA. First, as demonstrated in previous conflicts, they are easily malleable to Kony’s aims and are eager to accept his orders. “Children copy exactly what is taught during training,” one former junior commander observed. They don’t put on a show.” According to an NGO worker, Kony targets youth because he can model them and they’ll like him. Former insurgents recognize the strength that children may bring to a group: “Kony commands thousands of… youth whose allegiance is unquestionable.” His strength is immense.” Although this perception is perhaps enhanced by the fact that hundreds of youth flee the LRA each year, the fact remains that Kony uses youth as a vital resource (Denov and Piolanti, 2021).

The LRA uses youth as disposable porters, as they walk quickly and tire slowly. This improves the LRA’s mobility and its ability to transport loads of plundered items over long distances, which is essential for the group’s ability to resupply with food, boots, and money. After escaping for a month, a young person confessed, “I carried the injured and didn’t use the gun. During raids, we would steal food and enter homes to inquire about the location of the food. slower kids were slaughtered, saying, “They ransacked our home and the homes of our neighbors, abducting ten boys and four girls. To the Ogili Hills, we hauled the booty. A young child of twelve years old threw the suitcase down on the way there because he was exhausted. He was instantly shot to death.”They beat my uncle, then made us carry bombs, grenades, and bullets,” one abducted girl recalled. Our feet grew larger as a result of our lengthy walking(Veale and Stavrou 2007).

Third, Abducted youth were forced to kill their friends or family members in front of other abductees instilling fear and discouraging them from escaping. This ensures a clean break from the past, as youth are less likely to return to a community where they have been murdered and tortured. Atrocities against soft-target civilians spread fear and chaos through the population, a guerrilla warfare tactic that denied intelligence to the government and left the rebels free to loot. A single vicious killing can force hundreds of people to flee from their homes in a particular sub-county, leaving behind their planted crops and numerous possessions for easy looting. Again, numerous testimonies bear out this three-pronged logic: “We killed people so that people would fear us,” recollected one ex-combatant. A formerly abducted girl added, “They teach you ‘don’t fear’, otherwise you will be killed. They test your fear; they tell the youth to kill an escapee otherwise you are killed. This is not done to everyone, but they see you are weak, and then they test you. They know these things.” Kony’s manipulative control is comprehensive(O’Callaghan et al. 2014).

Another reason for involving youth was that, after his revolt (which purported to be seeking liberation for the north of Uganda) lost regional support, Joseph Kony began abducting youth to bolster the ranks of his army. The LRA combines martial and spiritual aspects, and Kony leads the group with cult-like beliefs, the most significant of which is his total authority. Abducted girls are raped repeatedly as ‘wives’ of LRA officials, while boys are compelled to join ruthless warriors. Kony inducts these youth by forcing them to see and commit heinous atrocities, like as murdering family members. This is one of the methods he used to persuade his captives that there is nothing for them to return to(Veale and Stavrou 2007).

The war and the violence they witnessed changed their lives

Still stigmatized are moms who were abducted as babies and children born in LRA captivity. The Justice and Reconciliation Project’s “We Are All the Same” report indicated that these youth are afraid to share their backgrounds with their friends and have a hard time processing the horrific events they went through while living in the bush (Annan and Brier 2010).

According to John Muto p’Lajul from the Kitgum district, “the scars are still there for former ‘wives’ of former LRA combatants and their kids who are being rejected by their maternal uncles.” “While their children are growing up without land to inherit and dwell in, the wives are no longer able to have committed relationships. This is a major problem.”

References

Annan, Jeannie, and Moriah Brier. 2010. “The Risk of Return: Intimate Partner Violence in Northern Uganda’s Armed Conflict.” Social Science & Medicine 70 (1): 152–59.

Denov, Myriam, and Antonio Piolanti. 2021. “Identity Formation and Change in Children and Youth Born of Wartime Sexual Violence in Northern Uganda.” Journal of Youth Studies 24 (9): 1135–47.

Kelly, Jocelyn TD, Lindsay Branham, and Michele R. Decker. 2016. “Abducted Children and Youth in Lord’s Resistance Army in Northeastern Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC): Mechanisms of Indoctrination and Control.” Conflict and Health 10 (1): 11. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13031-016-0078-5.

Mwambari, David. 2021. “Transcultural Memory in Post-Conflict Northern Uganda War Commemorations.” Africa Development / Afrique et Développement 46 (4): 71–96.

O’Callaghan, Paul, Lindsay Branham, Ciarán Shannon, Theresa S. Betancourt, Martin Dempster, and John McMullen. 2014. “A Pilot Study of a Family Focused, Psychosocial Intervention with War-Exposed Youth at Risk of Attack and Abduction in the North-Eastern Democratic Republic of Congo.” Child Abuse & Neglect 38 (7): 1197–1207.

Radstone, Susannah. 2020. “Working with Memory: An Introduction.” In Memory and Methodology, 1–22. Routledge.

Royo, Josep Maria. n.d. “War and Peace Scenarios in Northern Uganda.”

Veale, Angela, and Aki Stavrou. 2007. “Former Lord’s Resistance Army Child Soldier Abductees: Explorations of Identity in Reintegration and Reconciliation.” Peace and Conflict: Journal of Peace Psychology 13 (3): 273–92.