Introduction

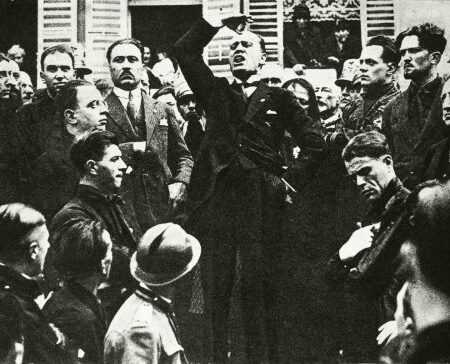

Students have played an essential role in the political history of Bangladesh since its emergence as an independent nation. As the pioneers of change, students were the first to fervently embrace Bangladesh’s national identity and join the political struggle for an independent state. Since its inception, Bangladesh has witnessed numerous significant socio-political movements that have altered the destiny of the entire nation. These movements have been propelled by the unwavering support, enthusiasm, and aspirations of students. It all began 71 years ago when a small group of students marched together toward the East Pakistan Legislative Assembly Building (Asjad, 2023).

Bangladesh’s history is interwoven with the spirit of student activism, dating back to the time before independence. It was the students who led the protests in the streets for the recognition of the Bengali language during the 1952 Language Movement. Eventually, Bengali was acknowledged as the official language of East Pakistan, marking a significant turning point in the country’s quest for linguistic and cultural identity.

In recent years, student activism has taken new forms but one common aspect connecting the events of 1952 to the present day is students’ commitment to social progress and the development of the country. To develop this point, my essay examines the Shahbagh Movement of 2013 and The Road Safety Movement of 2018 both of which provide compelling evidence for how student activism has transformed over the years and emerged as a strong tool for safeguarding the rights of citizens in Bangladesh. My essay also examines the impact of the Language Movement in 1952 on these movements. I show the ways in which the Language Movement in 1952 acts as a catalyst that has not only encouraged the development of student activism in Bangladesh but also the formation of contemporary student-led movements. My essay pays attention to the parallels as well as the distinctions in approaches and objectives of these different movements.

Historical Context

Understanding the intricacies of the sociocultural contexts in other significant contemporary movements, (the Shahbagh Movement in 2013 and the Road Safety Movement in 2018, for instance), becomes impossible without delving deeper into the goals and objectives of the Language Movement in 1952. In his memoir titled “The Unfinished Memoirs,” Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, the founding father of Bangladesh, portrays the Language Movement as a pivotal moment in Bangladeshi history that ignited a fresh wave of student activists dedicated to the nation’s independence. The book underscores the pivotal role that students and young intellectuals played in shaping Bangladesh’s overall politics. This influence continued to be true even in the period before 1952, as illustrated by the book. During the anti-colonial struggle, notable leaders of the Muslim League (a political party that emerged to represent Muslims in British India) began to rely on students; mainly due to the majority of the region’s intellectuals and professionals, including businessmen, doctors, and lawyers, being Hindu. Consequently, the people in the Bengali provinces began recognizing the potential of students as crucial political activists (Maniruzzaman, 1988).

From this realization, student activism started to burgeon in the East Bengal province, and students actively engaged with various socio-political groups, participating in several political issues. This involvement fostered a sense of unity and solidarity, evident in the events of 1952 and beyond.

Contemporary Scenario of Growing Student-led Movements and Activism

In the contemporary period, the Shahbagh Movement of 2013 emerged as a significant movement, initially led by students. This movement was ignited in response to the International Crimes Tribunal’s (ICT) decision, which sentenced Abdul Quader Mollah, a prominent member of the Jamaat-e-Islami party, to life in prison for his involvement in war crimes during 1971. Mollah’s conviction included charges of murder, rape, and torture. For many, this verdict appeared inadequate considering the gravity of Mollah’s offenses, leading them to call for the death penalty for all individuals found guilty of war crimes. The second event that I examine is the Road Safety Movement, during which thousands of students blocked roadways and intersections, causing gridlock throughout the city, demanding safer roads and accountability for reckless driving. The protesters demanded better road infrastructure, effective traffic management, and harsher penalties for traffic violations. They also called for an end to corruption within the transportation sector. Moreover, they wanted the authorities to take immediate actions to prevent road accidents and improve road safety. The protesters stopped trucks, buses, and cars and demanded to examine the drivers’ licenses and inspect the condition of the vehicles for roadworthiness (Pokharel, 2018). “Our ancestors did it in 1952, we, as forerunners of the martyrs of the Language Movement, will do it too. We will bring about the change,” proclaimed one of my interlocutors (anonymous, Interviewee 4).

A protestor of the Road Safety Movement said, “We won’t stop until justice is served! We’ll shout from the tops of buildings and march through the streets! We are this country’s future, therefore we will not be victimized or kept quiet. We shall battle for our rights and demand justice just like our brave ancestors did in 1952.” (The Daily Star, 2018). Many videos went viral and this was one of the videos in which a student refers to the language movement as their own protest. These words encapsulate the resounding chants of the protestors during the Road Safety Movement, drawing inspiration from the Language Movement as an ideal instance. This reference to the Language Movement served as a catalyst, igniting a profound sense of nationalism and patriotism among the people of Bangladesh. However, Analysts claim that although the student protests were mostly about improving road safety, they also represented the public’s mounting dissatisfaction with the administration. Michael Kugelman, a South Asia specialist at the Woodrow Wilson Center in Washington, thinks that the protests were an outpouring of long-suppressed rage against the government and its policies as a whole (Islam, 2018).

How Contemporary Student Activism Commemorates the Language Movement

“History always influences people, especially when you have something to be very proud of. Language movement is such a pride that a Bengali can never forget. We still hold it in our hearts. However, there are huge transformations you can observe if you compare the activism in 1952 and the contemporary” – said one of my interlocutors (Interviewee 1) a student of Dhaka University who actively participated in both the Shahbagh Movement and Road Safety Movement. My interviewee’s statements are corroborated by secondary scholarship. According to Ullah (2016), the Language Movement provided students with a forum to organize and express their political objectives, which later sparked the growth of student-led organizations for democracy and social justice. Ullah adds that students in Bangladesh were motivated to take part in larger social and political movements by the Language Movement.

Najim (Interviewee 2), an activist, and writer who participated in the Shahbagh Movement, shared his experiences of engaging with students who infused the movement with a new viewpoint, vigor, and an idealistic spirit. After participating in movements out of curiosity, he gradually started to engage in activism, specifically, online activism. According to him, the students were motivated by a tremendous desire to uphold the principles of the Liberation War and the values of justice and accountability that the movement represented. He believes their strong involvement promoted widespread mobilization and boosted the Shahbagh Movement’s importance and influence as a whole, as they invoked the struggles of common Bengali people during the language movement and the Liberation War.

However, while contemporary movements invoke the historical memory of the language movement, the approaches and objectives of these newer struggles have shifted over the years. One of the crucial transformations is activism through digital and social media platforms. Rafsan (Interviewee 05), a fresher in BRAC University, shared his experience about participating in the Road Safety Movement, which boosted his confidence for the first time to stand in roads protesting for a change. Similarly, Tanvir, a former SUST (Shahjalal University of Science and Technology) student (Interviewee 5), believes that it is easy to be united against outsiders because at that time the ideology was clear. However, it is very difficult when you stand against someone who also belongs to a similar socio-cultural background. He said:

“Then (1952) it was the outsiders (Pakistani Occupation), but now it is self vs self.”

The Impact of Social Media on the Nature of Student Activism

“Technology helped us spread the word and made things easier on the ground. We notified people about any updates or changes through social media, and live videos on Facebook kept people engaged with the protests,” shared Anika Haque Ananya, a student from Viqarunnisa Noon School and College who was actively involved in the Road Safety Movement in 2018 ( Monamee, 2020). During the Road Safety Movement in 2018, different types of students from schools, colleges, and universities organized peaceful protests, traffic blockades, and sit-ins. They successfully coordinated their efforts by using social media, to disseminate their message and urge popular involvement. Students’ involvement in the movement’s front lines attracted a lot of media attention and popular support. “In the realm of digitalization, it has been much easier to coordinate, organize, support, and amplify a message of activism. While doing so, it had played an effective role in spreading the movement to a wider audience.” For example, with the hashtags #RoadSafetyMovement and #WeWantJustice, slogans, videos, and photographs became popular on social media when the road safety movement first started (Monamee, 2020). For the first time in decades, they have organized protests in Bangladesh that are nonviolent, timely, and inclusive using social media (Jawad, 2021). Furthermore, the proclamation of Shahbag as a social media movement validates itself because social media played a key role in every stage of the protest. Bloggers and Online Activists initiated the Shahbag movement.” according to Chowdhury (2018).

Furthermore, transnational solidarity networks have provided student activism with fresh vitality and resources, allowing them to learn from each other’s approaches, and also to forge alliances with other social groups. In the context of the Shahbagh Movement, the form of leadership was initially adaptable and participative and changed throughout the history of the movement, culminating in the growing use of social media as a tool of communication of this movement.

Additionally, there is a meaningful way of viewing the Shahbagh Movement and student involvement by studying the activities of another group formed in opposition to the opposition movement. The group is called Hefazat-e-Islam, which is an Islamic political organization formed up of students and activists from Qwani Madrasa who are fiercely opposed to the Shahbag movement. Two types of student groups participated in the whole event; the Shahbagh group and the Hefazat-e-Islami group. A significant number of students actively participated in both groups and connected their opinions to the metanarrative of Bengali nationalism vs. Islamic identity, and religiosity vs secularism.

A professor (anonymous, Interviewee 3) at Dhaka University, offered his viewpoint on student action in light of his own experiences. Sharing his experiences of the student movement, one of my interviewees who is a professor at Dhaka University emphasized how many students, even those from non-Bengali roots like himself, actively participated in different types of activism when they were students. He did, however, add that the language movement had a tremendous impact on Bengali activism and has even inspired other non-Bengali populations, such as indigenous people, to speak out and demonstrate their rights. “I never felt excluded from the mainstream community when I participated in different socio-political movements. However, if you notice the recent activism, particularly in public universities, you will find, most of it is forceful and has its own political agenda, which was not the case in 1952. As people were united against the injustice of the Pakistani regime. Technology has made activism more accessible and mobilized, but there are drawbacks as well. It has brought us under the eyes of surveillance, which restricts us from freely expressing our opinions, or doing any other activities”.

The mode of communication and information dissemination is one of the key distinctions between 1952 and contemporary activism. The exchange of information and communication during the Language Movement in 1952 mostly depended on conventional techniques, including in-person gatherings, protests, speeches, and print media like newspapers and pamphlets. To mobilize and disseminate their message, activists have to rely on face-to-face encounters and being there physically. Because there were few communication channels available, it took a lot of planning and coordination to organize large-scale protests. On the flipside, face-to face communication reduced the fear of state surveillance that plagues contemporary activism. Activists fear that their activities are being checked and monitored by the state. Increased government surveillance has engendered a general sense of fear and anxiety among student activists. A secular aspiration was present during the 1950s and 1960s era. Due to the advancement of technology, activism shifted online, and social media became a battleground/space to protest, which has both positive and negative aspects.

Conclusion

While activism during the language movement era and contemporary times significantly transformed, it is important to note that both shared the same objectives of promoting social justice, human rights, and positive societal change. A movement never fails, whether the demand is fulfilled or not, but it creates a sense of unity that inspires the next generation. The language movement was such a movement that created the necessity to make students worthy of taking on the responsibility of the country. Thus, beyond its immediate goals, the Language Movement has played a significant role in the development of student activism in Bangladesh. The movement highlighted the importance of language as a statement of identity, diversity, and inclusion. It inspired future activists to include language rights in their larger fights for social justice, gender equality, rights for workers, environmental preservation, and democratic government.

References

Asjad, T. (2023, February 17). History of language movement for new generations. The Financial Express. https://thefinancialexpress.com.bd/views/opinions/history-of-language-movement-for-new-generations

Maniruzzaman, T. (1988). STUDENT POLITICS AND MASS UPHEAVAL. In The Bangladesh Revolution and its Aftermath (Second ed.). The University Press.

Monamee, M. I. (2020, August 14). Road Safety Movement 2018: Was it worthwhile? The Daily Star. https://www.thedailystar.net/star-youth/news/road-safety-movement-2018-was-it-worthwhile-1944557

Pokharel, S. (2018, August 06). Bangladesh protests: How students brought Dhaka to a standstill. CNN. https://edition.cnn.com/2018/08/06/asia/bangladesh-student-protests-intl/index.html

Rahman, S. M. (2012). The Unfinished Memoirs. University Press Limited.

Islam, A. (2018, 08 08). Why Bangladesh protests are not just about road safety. D W. https://www.dw.com/en/why-bangladesh-student-protests-are-not-just-about-road-safety/a-45007297