Introduction

What we know today as ‘LGBTQ+’ is an acronym that stands for “Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, Queer….” It indicates a defined group of queer people that shares a common culture and is united by militating in common social movements. ‘Queer’ is often used as an umbrella term to denote sexual orientation or identity within a particular community.[1]

Its traces can be found all the way back in the 19th century, however, it can all be traced back even further, in the times of the ancient Greeks. In fact, same-sex relationships were no secret and people were very used to them, in the old Greek society. This changed during the medieval times when the Catholic religion had become entrenched, and when European countries began to introduce laws against people in same-sex relationships, based on national traditionalism and religious beliefs.

In fact, laws continued to be really harsh towards those people, and same-sex activity began to be seen as a sin, as something outrageous. So that people pursuing these kinds of relationships had to hide who they really were and try to conform with the hetero-normative value system on which societies were based.

Thanks to the social-rights movements, awareness of the need to protect with rights this community against continuous acts of discrimination increased in the 21st century, mainly in the Western part of the world, as these acts highly affect the daily lives of the community. However, there is still a lot to do.

With my research project I want to bring an Italian perspective to queer studies, since I think that it would be useful to show what a teenager in a close-minded society has to go through and what consequences those difficulties bring to the process of developing one’s identity.[2]

The people I chose to interview are a group of students who used to live in the area of Castelli Romani and faced may difficulties because of their identity. What they have in common is the fact that they all left Italy and moved to a more open reality in order to have the freedom to show who they really are. In addition, I chose to study such topic as I think it is still an understudied issue.

What I have been asking myself during the realization of my project is how the public perception of the LGBTQ+ community in a more inclusive reality is and if this community is really free to express itself in different environment.

Italy and the LGBTQ+ Community

Italy as a country still needs to do a lot to work, as it is still grappling with social issues connected to the LGBTQ+ community. In particular, the LGBTQ+ community is splitting public opinion as well as the Italian government itself.

Italy’s history with queer people can be traced back to ancient times, with the ancient Greeks, Etruscans and, later, Romans. It followed the same steps of the European and Western trend of same-sex attraction. After the Middle Ages, when homosexuality began to be seen negatively, with the Renaissance it was re-discovered, but queer people were still dealing with harsh oppression and acts of violence. [3]

Over the 19th and 20th centuries, Queer people were still facing a strong censorship and continued to hide themselves, also because sodomy was still considered as something very scandalous. Furthermore, there were no explicit laws restraining the LGBTQ+ community but being queer was still not supported and accepted.[4]

Things drastically changed in 1969 thanks to Massimo Consoli. He was a historian and was also considered as the father of the Italian gay community. He published the “Manifesto per la Rivoluzione Morale: l’Omosessualità Rivoluzionaria” (Manifest for the Moral Revolution: The Revolutionary Homosexuality), which helped bring about the organization of the first LGBTQ+ association. From that point onwards, a series of activists and movements were publicly fighting for the acceptance of such community by society.

This fight is still continuing today since the Italian country is still marked by an intense sense of homophobia and society is still very divided when it comes to talking about such topics.[5]

Nowadays, homophobia in Italy is articulated through both physical and verbal violence. In fact, as we can witness in the figure 1, acts of discrimination of all types are spread cross the whole country. In this chart there are acts that are being reported to public authorities and are penally relevant but, nevertheless, we can still count a victim of these crimes every two days. The most common place where these events happen are the streets – in fact, here they take place in the percentage of 44% – which is followed by the 11% registered in places linked to leisure time. Not exempted from these crimes are the workplace and school, where the tally is lowered to a general number of 10%.[6]

Another important source of violence can be found directly in families, where 18% of the victims is registered. In fact, as I had to chance to get know in the interviews that I have conducted, all the interviewees share the fact that one of the main sources of rejection came from their families, to the point that their identity became something a taboo and that it is best to leave hidden.[7]

In order to fight all those types of discrimination that can happen in daily life, many activists and associations have been fighting in order to reach a satisfactory level of safety for people belonging to the LGBTQ+ community.

One of the people that we have to acknowledge in this fight, who came to notoriety in the last decade, is Alessandro Zan. He can be described as a left-wing politician, and he is also a leading member of one of the major Italian pro-LGBTQ+ associations, “Arcigay.” During his political career he has been fighting for an absolute equality for LGBTQ+ people and managed to achieve the recognition of same-sex couples. To bring forward his ideals, in 2021 he published the “Zan bill”, a legislative proposal. It envisioned the establishment of an aggravating factor for crimes perpetrated in the name of discrimination based on sex, gender, sexual orientation. He wanted also to establish a national day against homophobia and, lastly, he wanted to create a national strategy to prevent discriminations of that kind.

Italy is strongly polarized on such issues. On one side, we have parts of the parliament and the church which are at all costs against the establishment of such a bill as it would endanger freedom of expression, pave the way for “homosexual propaganda” in schools, and violate the agreement between the state and the church.[8] The rest of society, in contrast, felt the need of this bill in order to promote equality and to reduce discrimination.

Eventually, the bill was not passed but the majority of the public opinion was in favour of such bill and thousands of people gathered in the streets to protest against such a decision as they considered the “Zan Bill” as incredibly important for the development of society.[9]

Forming Identities in Italy

As we have witnessed the Italian history and population is strongly divided in two when it comes to talking about the LGBTQ+ community. On the one hand, there are people who are totally against everything that is not considered “normal” and doesn’t conform with the heteronormative patriarchal society that Italy is built upon; on the other side, we have the segment of the population that is fed up with these old ideologies, and that is fighting for the realization of an equal society and to bring the Italian country towards a more open-minded reality.[10]

For this reason, young queer people are finding it difficult to live in a country with these living conditions. This is because this general feeling of hate and lack of acceptance highly influences the way they grow up and they take their place in society.

Concerning the interviews that I have conducted, I was struck by the fact that all of my interviewees share the same experiences when it comes to talking about their process of knowing who they are, which was majorly influenced by two environments: the family and the school.[11]

The interviewees shared the fact that they felt rejected by their families, so much that they preferred to hide who they really were in order to avoid creating conflicts in the family.[12] They felt unsafe at home and preferred spending time outside of the domestic context. This is because many Italian households are influenced by the Vatican, which still has a huge hold on the politics and culture of Italy. Indeed, parents raise their children with the idea of the “perfect family,” causing the development of the idea that everything that is not ‘normal’ is not okay.[13] That leads to internalized homophobia built on the teachings of one’s parents. The people I have interviewed, and some of the people whom they met in their journeys, share comparable stories.[14]

Another common outcome that I have received is their perception on their high school experience. In fact, among the people I have interviewed, Riso Mercuri was a person who found themselves in the position of having to change school because people got to know their identity and started to judge them. When Riso changed high school, they choose to go to the “M.T. Cicerone” high school, which is the same myself and the other fellow interviewees have attended in Castelli Romani.[15] They agree that the environment that we all had in that high school is what really helped them to get know themselves. This is because the students and the teachers, with minor exceptions, were really open minded and this helped students belonging to the LGBTQ+ community to know each other and develop this sort of new community that could be used to find someone who accepts you as you are, when other people don’t, since these sympathisers are in the same position as you. Hence, this helped them to figure out that their orientations were normal and acceptable.

However, having found this strong community in high school did not help build this sense of belonging to Italy, since discrimination outside the school is harsher. This, and their family situation, are what made my interviewees leave the country to reach an open society where they would not be discriminated.

The European Reality

As we have witnessed for Italian history, a LGBTQ+ community can be found in other European countries since archaic times, when same-sex relationships were common, until the establishment of Christianity, which institutionalized the heterosexual marriage.[16] Since this period, same-sex activity became penally persecuted with harsh consequences.

This continued until after World War I, when academic studies on subjects such as human sexuality became acknowledged, and this helped the organization of a series of conferences that ended in 1921 with the creation of the World League of Sexual Reform. This established the legalization of all sexual acts between consenting adults, regardless of their sex. The League also campaigned for gender equality, comprehensive sex education, and reforms to eliminate the dangers of prostitution. The first successful sex reassignment surgery was one of the most well-known achievements of the academic institutions connected to these efforts. The first person to successfully have this operation was Lili Elbe, who has been since known as “the Danish Girl”.[17]

During the rise of totalitarianisms, there were a general deterioration of civil liberties, and a strong censorship, that prompted queer people to be highly discriminated and obliged to hard labour or to undergo a conversion therapy.

A turning point was marked by what happened in the Stonewall inn in America in the sixties. Stonewall inn was a club where queer people could find a space of liberty, nevertheless this location was always monitored by the police, which eventually took on that club, inadvertently starting a massive series of revolts, which spread to Europe.

Pride parades debuted in London in 1972, with two thousand people, with the aim to vindicate their freedom of expression. The crowd, over time, increased and pride parades spread in all Europe. The first steps towards equality came from North-Eastern Europe, while Eastern Europe had to wait until 1999 for their first pride parade, and in some other countries it is still illegal to our days.

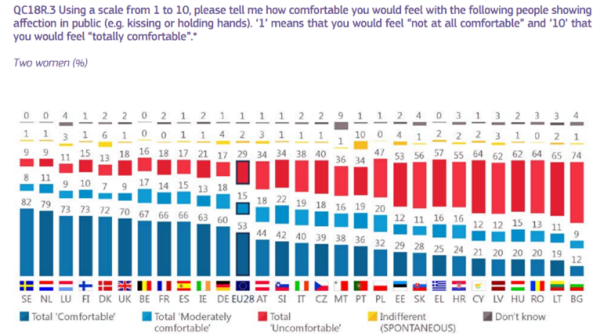

Following the survey conducted by the European commission, we can notice some trends in certain areas, in 2019.

This first graphic deals with the public opinion regarding the acceptance of same-sex marriages.

We can notice that the graphics are “organized” in geographic areas, unintentionally.

In fact, on the right side, we notice a vast number of countries that are situated in the Eastern area of Europe. Here, as we can see, the situation is not ideal, as the percentage of people who think that there is nothing wrong in homosexual relations is between 57% to 20%, the latter registered in Bulgaria. Italy is situated almost at the centre of the graphic, with 59% percent of people who do not have problems with LGBTQ+ relationships. On the left, we see countries that belong to the Northern part of Europe, which range from a percentage of acceptance registered in Finland with 79%, to 95% in Sweden.

The second graphic deals with the comfortableness a person may have in seeing public affection coming from homo-sexual couples. We could say that is similar to the previous one. In fact, on the left side we have the more open countries that do not have problems with seeing affection in public, which coincide once again with the countries that are situated in the Northern area of Europe. On the right side, we have the countries located in the Eastern part of Europe, which do not even reach 50% of people that do not have any sort of problem with same-sex public affection. Italy is situated, again, almost at the centre of the graphic but, in any case, its complete degree of acceptance does not reach 50%.

Comparing it with the previous graphic, we notice that in every country the percentage of complete acceptance of heterosexual public affection is over 50%.

A debate that has been polarizing European public opinion is about gender. Many people are still holding on to the concept of gender based on the division between males and females that always coincides with the gender you get assigned at birth. People who do not identify with this definition are many, and they would like to enjoy an equal degree of recognition to the one enjoyed by heteronormative genders, even if the majority of society is against such “modern things,” as many people would define them.

The last two graphics of this page, deal with the recognition of transexual and non-binary people, who by definition are the people who do not identify with the gender assigned at birth. We notice that in almost every country the acceptance does not reach half of the population.

However, still here we can notice the same trends, with the exception of Malta. In fact, Northern Europe is on the left and Eastern Europe on the right, with Italy still having less than 50% of its citizens who accept these trends. The Italian position and the overall European one over these topics represent what is influencing the decision of many young people to leave their hometown in order to go to a more open reality that coincides with Northern Europe. As a matter of fact, the people the I have interviewed all chose to leave their country because of their families’ and nation’s limited acceptance of their identity, and decided to go to The Netherlands, Norway, or Germany.[18]

Moving into a New Reality

Moving in a new country without family or friends, completely changes life. In fact, moving gives you the opportunity to build up a different environment around you that enables you to develop your personality and your identity.

What struck me I that all the people I have talked to share similar experiences, even if they have different personal situations and destinations. The interviewees told me that at the beginning they were afraid of moving even if they knew that it was the right choice to make to be what they wanted to be. It ended up being the best decision they ever made, also because such countries have more opportunities for work and education than the Italian country.

Indeed, Gee Reale, one of the people I have interviewed, has explicitly said that the decision to move to Germany was the best decision they have ever made, and it gave them the opportunity to feel reborn. This is because in the new countries that they now call home, the LGBTQ+ community firstly benefits of more rights, and secondly people will not judge you for your identity[19]. This is what I believe to be the main thing someone who is exploring their identity looks for and needs. Indeed, knowing that no one will stare at you for holding hands with someone, or for the way you express yourself, enables you to be who you are without being afraid that something bad may happen to you.

Even though at the beginning it was scary because they could rely only on themselves, they have all managed to build strong connections with people around them, thanks to the sharing of similar experiences and to the great diversity of people those countries offer.

What they all shared at the end of the interviews is that they would make such decision, as Sonia Polidori in particular said, a hundred times, if necessary, because the idea of knowing that there is a place where you have more opportunities and less worries about your identity is what young queer people in a close-minded reality are holding on to. [20]

However, people who moved abroad have different feelings towards their home country. In fact, it depends very much on the reason you left your country, and in my interviewing process I uncovered different reasons for doing so. Indeed, some, like Asia Celani,[21] said that they are missing the culture and the warmth that denotes Italian people, notwithstanding their position on such issues. People like Alice Conforti[22] share the fact that they do not miss at all their home country because it was not feeling like “home” and prefer the new environment they have created around them. On the other hand, there are people like Riso Mercuri[23] who prefer their new country but are still feeling a strong connection to Italy.

Conclusions

Taking into consideration everything that I have dealt with during this project, the LGBTQ+ community has been facing discrimination and violence for thousands of years, and knowing that its situation is now just slightly better is really striking. As a matter of fact, Italy and the rest of Europe’s records on this matter are not so different. Even though we see a part of Europeans who are beginning to broaden their minds, there is still the majority of European countries where the local LGBTQ+ communities’ members are facing many difficulties and, just by publicly revealing themselves, could face harsh consequences and critiques coming from the entire surrounding societies.

However, I think that the world, in this very moment, needs more education and more empathy towards the LGBTQ+ community because is unfair that people in the 21st century still feel the need to hide themselves and to change country in order to be completely free of judgements.

Even if we have seen that the situation is improving, it is not enough, and we still need a lot of time to really build a fair society where we can be who we really are.

[1] Hidalgo, D. Antoinette and Barber, Kristen. “Queer.” Encyclopedia Britannica, January 23, 2017. https://www.britannica.com/topic/queer-sexual-politics

[2] “Europe and LGBT Pride: A History,” My Country? Europe., June 28, 2019, https://mycountryeurope.com/culture/europe-lgbt-pride/.

[3] L. Benadusi, “La Storia Dell’omosessualita’ Maschile: Linee Di Tendenza, Spunti Di Riflessione E Prospettive Di Ricerca,” Rivista Di Sessuologia 31, no. 1 https://moodle2.units.it/pluginfile.php/196549/mod_resource/content/1/Benadusi-2007.pdf. P. 2-3

[4] Ibid. p. 3-8

[5] Hannah Roberts, “LGBT Hate Crime Bill Polarizes Italy,” POLITICO, May 21, 2021, https://www.politico.eu/article/lgbt-hate-crime-bill-italy/.

[6] “Omofobia.org – Cronache Di Ordinaria Omofobia,” www.omofobia.org, accessed 27 June 2022.

[7] Group of queer students located in Castelli Romani, interviewed by author, online interviews, May 27, 2022; May 28, 2022; May 30, 2022; June 4,2022.

[8] Giovanni Viafora, “Il Vaticano Si Scaglia Contro Il Ddl Zan: ‘Fermate La Legge, Viola Il Concordato,’” Corriere della Sera, June 22, 2021, https://www.corriere.it/cronache/21_giugno_22/vaticano-ddl-zan-legge-testo-b13294ba-d2d0-11eb-9207-8df97caf9553.shtml.

[9] Sky TG24, “Pride, a Roma Torna Il Corteo per I Diritti Lgbt. FOTO,” tg24.sky.it, accessed June 27, 2022, https://tg24.sky.it/cronaca/2022/06/11/pride-roma-foto#02.

[10] Hannah Roberts, “LGBT Hate Crime Bill Polarizes Italy,” POLITICO, May 21, 2021, https://www.politico.eu/article/lgbt-hate-crime-bill-italy/.

[11] Group of queer students located in Castelli Romani, interviewed by author, online interviews, May 27, 2022; May 28, 2022; May 30, 2022; June 4,2022.

[12] Group of queer students located in Castelli Romani, interviewed by author, online interviews, May 27, 2022; May 28, 2022; May 30, 2022; June 4,2022.

[13] Jacqui Gabb et al., “Paradoxical Family Practices: LGBTQ+ Young People, Mental Health and Wellbeing,” Journal of Sociology 56, no. 4 (2019): 535, https://www.academia.edu/49793421/Paradoxical_family_practices_LGBTQ_young_people_mental_health_and_wellbeing.

[14] Group of queer students located in Castelli Romani, interviewed by author, online interviews, May 27, 2022; May 28, 2022; May 30, 2022; June 4,2022.

[15] Riso Mercuri, interviewed by author, online interview, 04/06, 2022

[16] Annika Pietrus and Annika Pietrus, “The Right to Love: A Brief History of LGBTQ+ Rights in Europe,” The New Federalist, October 10, 2021, https://www.thenewfederalist.eu/the-right-to-love-a-brief-history-of-lgbtq-rights-in-europe?lang=fr.

[17] Naomi Blumberg, “Lili Elbe | Danish Painter | Britannica,” in Encyclopædia Britannica, 2020, https://www.britannica.com/biography/Lili-Elbe

[18] “Omofobia.org – Cronache Di Ordinaria Omofobia,” www.omofobia.org.

[19] Gee Reale, interviewed by author, online interview, 27/05

[20] Sonia Polidori, interviewed by author, online interview, 30/05

[21] Asia Celani, interviewed by author, online interview, 30/05

[22] Alice Conforti, interviewed by author, online interview,28/05

[23] Riso Mercuri, interviewed by author, online interview, 04/06

Bibliography

- rainbow-europe.org. “Annual Review | Rainbow Europe,” n.d. https://rainbow-europe.org/annual-review.

- Benadusi, L. “La Storia Dell’omosessualita’ Maschile: Linee Di Tendenza, Spunti Di Riflessione E Prospettive Di Ricerca.” Rivista Di Sessuologia 31, no. 1 (n.d.). https://moodle2.units.it/pluginfile.php/196549/mod_resource/content/1/Benadusi-2007.pdf.

- Blumberg, Naomi. “Lili Elbe | Danish Painter | Britannica.” In Encyclopædia Britannica, 2020. https://www.britannica.com/biography/Lili-Elbe.

- Bubola, Emma. “Bill Offering L.G.B.T. Protections in Italy Spurs Rallies on Both Sides.” The New York Times, October 17, 2020, sec. World. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/10/17/world/europe/italy-lgbt-hate-crimes.html.

- European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights. “Current Migration Situation in the EU: Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender and Intersex Asylum Seekers,” March 24, 2017. https://fra.europa.eu/en/publication/2017/current-migration-situation-eu-lesbian-gay-bisexual-transgender-and-intersex.

- Dahl, Angie L., and Renee V. Galliher. “LGBTQ Adolescents and Young Adults Raised within a Christian Religious Context: Positive and Negative Outcomes.” Journal of Adolescence 35, no. 6 (2012): 1611. https://www.academia.edu/26463932/LGBTQ_adolescents_and_young_adults_raised_within_a_Christian_religious_context_Positive_and_negative_outcomes.

- Di Feliciantonio, Cesare, Cesare Di Feliciantonio, and Kaciano B. Gadelha. “Situating Queer Migration within (National) Welfare Regimes.” Geoforum 68 (2016): 1–9. https://www.academia.edu/19055434/Situating_queer_migration_within_national_welfare_regimes.

- eu. “Eurobarometer,” n.d. https://europa.eu/eurobarometer/surveys/detail/2251.

- Hidalgo, D. Antoinette and Barber, Kristen. “Queer.” Encyclopedia Britannica, January 23, 2017. https://www.britannica.com/topic/queer-sexual-politics

- My Country? Europe. “Europe and LGBT Pride: A History,” June 28, 2019. https://mycountryeurope.com/culture/europe-lgbt-pride/.

- European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights. “EU LGBT Survey European Union Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual and Transgender Survey Results at a Glance EQUALITY,” https://doi.org/10.2811/37741.

- Gabb, Jacqui, Elizabeth McDermott, Rachael Eastham, and Ali Hanbury. “Paradoxical Family Practices: LGBTQ+ Young People, Mental Health and Wellbeing.” Journal of Sociology 56, no. 4 (2019): 535. https://www.academia.edu/49793421/Paradoxical_family_practices_LGBTQ_young_people_mental_health_and_wellbeing.

- Giuffreda, Angela. “Vatican Urges Italy to Stop Proposed Anti-Homophobia Law.” the Guardian, June 22, 2021. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2021/jun/22/vatican-urges-italy-to-stop-anti-homophobia-law.

- Giuffrida, Angela. “‘We’re Living in Fear’: LGBT People in Italy Pin Hopes on New Law.” The Guardian, July 26, 2020, sec. World news. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2020/jul/26/italy-lgbt-new-law-debate.

- Mole, Richard C.M. “Queer Migration and Asylum in Europe on JSTOR.” www.jstor.org. Accessed February 17, 2022. https://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctv17ppc7d.

- omofobia.org. “Omofobia.org – Cronache Di Ordinaria Omofobia,” n.d. https://www.omofobia.org/.

- Pietrus, Annika, and Annika Pietrus. “The Right to Love: A Brief History of LGBTQ+ Rights in Europe.” The New Federalist, October 10, 2021. https://www.thenewfederalist.eu/the-right-to-love-a-brief-history-of-lgbtq-rights-in-europe?lang=fr.

- Roberts, Hannah. “LGBT Hate Crime Bill Polarizes Italy.” POLITICO, May 21, 2021. https://www.politico.eu/article/lgbt-hate-crime-bill-italy/.

- Scandurra, Cristiano, Salvatore Monaco, Pasquale Dolce, and Urban Nothdurfter. “Heteronormativity in Italy: Psychometric Characteristics of the Italian Version of the Heteronormative Attitudes and Beliefs Scale.” Sexuality Research and Social Policy, August 1, 2020. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13178-020-00487-1.

- TG24, Sky. “Pride, a Roma Torna Il Corteo per I Diritti Lgbt. ” tg24.sky.it. Accessed June 27, 2022. https://tg24.sky.it/cronaca/2022/06/11/pride-roma-foto#02.

- “The Economic Arguments the Social Acceptance of LGBTI People in the EU This Document Presents a Selection of Graphs and Tables from the Special Eurobarometer ‘Discrimination in the EU’ with Detailed Data from Member States on the Social Acceptance of LGBTI People and Perceptions on Discrimination Based on Sexual Orientation, Gender Identity and Sex Characteristics,” 2019.

- Viafora, Giovanni. “Il Vaticano Si Scaglia Contro Il Ddl Zan: ‘Fermate La Legge, Viola Il Concordato.’” Corriere della Sera, June 22, 2021. https://www.corriere.it/cronache/21_giugno_22/vaticano-ddl-zan-legge-testo-b13294ba-d2d0-11eb-9207-8df97caf9553.shtml.