In 2013, Uganda hosted 220,555 refugees. Four years later, in 2017, that number had increased to 1,350,495. 1 Many of the new refugees arrived from South Sudan, driven to seek refuge by the civil war in their country. 2 Close to 60,000 refugees live in Kiryandongo settlement, located in north-western Uganda. 3 Indeed, most of Uganda’s refugee settlements are located in the poorer, rural, northern part of the country. Though Uganda has been internationally recognized for its response to refugees, many communities have showed hostility against each other in various clusters and blocks within different refugee camps, including Kiryandongo.

Kiryandongo is said to have registered 300 cases of conflicts, losing more than 50 lives, due to tribal clashes between 2013-2016, according to a woman group leader in cluster J. Putin Jane was part of a data collection initiative, they were tasked to conduct in 2016 by UNHCR, Save the Children and Danish Refugee Council. She personally experienced a situation of tribal conflict were by she was found interviewing a household In cluster OQ, and she was asked forcibly to describe her ethnic background and later on asked to leave as soon as she could. When she told me this story, she sighed heavily. What factors contribute to intertribal conflict in Kiryandongo, and what steps can communities take to build peace?

Drawing on oral history interviews with residents of Kiryandongo settlement from five tribal groups, this research highlights the role of social media, educational provision, and community leadership in helping to reduce intertribal tensions and create more peaceful conditions in the settlement. Whereas other discussions of intertribal conflict in Ugandan refugee settlements have focused on the role of surveillance and policing to reduce conflict, this research suggests a bottom-up approach, based on education, community organizing and collaboration, and youth empowerment. 4

What are the causes of intertribal conflict in Kiryandongo?

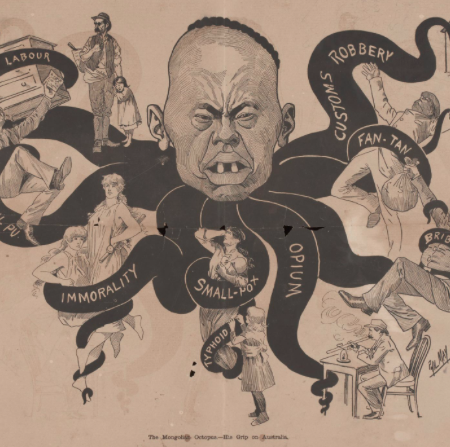

Interviews with young people, community leaders, and other residents of the settlement show that tribalism is mostly triggered by groups of social media personalities who have large audiences and popularity on social media platforms. These people are both based within South Sudan and outside South Sudan. Examples include online live shows by influential activists abroad, such as Deng Dinka, who quoted on an article posted on the 07-09-2020. 5 The post indicates of how he has been against the Twic for the last 07 years. On the other hand, another activist recognised as Mathiang Jalab caused panic on social media on the same date as he mentioned in his post “SPLM -IO is yet cooking another War.” This was in regard to a post by the CDE Dut Majokdit SPLM-IO Students peace league. There were mixed reactions after the post didn’t match with the caption which was shared and tagged.

Practices like these tend to incite fear, terror, bullying and tension to the masses of followers on their media platforms such as Twitter, Facebook, and WhatsApp groups.

It is not just activists and other known political actors whose use of social media inspires tension within the settlement. Tribalism is also triggered by false propaganda published by trusted media handles, such as Eye radio, Juba Eye, Juba Online TV, and Radio Miraya, amongst others. Their pages have been duplicated and faked to turn influential people against each other, which leads to tribal hatred and conflict.

Another significant cause of tribalism could arise from the way children are taught right away from childhood. Children are raised with a concept of hatred which grows in them. This is done by the elders whose intentions are to get revenge against other groups for past harms. Maan Ajah, now married with two children and business woman in Bweyale main market, says when she was young, she grew up with hatred of two specific tribes: the Murle and the Nuer tribe. The Nuer were said to have killed her husband’s father and mother during the war, and the Murle to have raided their village’s cattle, leaving the people in the village in hunger, suffering, and extreme poverty. From that time up to date, she has not and will not associate with these two tribes because of the hatred that was instilled in her mind. “I hate those people and I don’t want to associate with them, even in my business, I don’t care whether they come or not, it’s up to them. I am not willing to [take] revenge but I will never forgive them for what ever they did. I am suffering because of them,” says Maan Ajah, while she wipes out tears.

Maan Ajah’s story shows the ways that the narratives children grow up with travel with them when they seek refuge in Uganda, and continue to shape their understanding of, and relationships with, the different communities that live together in the settlement. Similarly, the influence of social media and geographically-dispersed activists and public figures shows that the conflicts within the settlement are embedded in larger, international, political and ethnic conflicts, and cannot be understood in isolation from that context.

Perspectives on reducing intertribal conflict

According to Betty Atoo, a cluster youth and social activist for women and girl child empowerment, people must disregard any information on social media that is not verified by the ministries or from the right sources. To verify, people can use built-in security tools on social media, such as the blue tick, especially on the social media handles of influential users such as prominent leaders, religious wings, and media houses, such as the South Sudan Broadcasting Network, JubaEye, Juba TV, the page of H.E. the President of South Sudan, SPLM-IO, and national and international NGOs the Red Cross. By following the right sources one is able to avoid false propaganda.

Similarly, John Doh Cho, a computer student, suggested that false propagandas should be disregarded and the culprits must face charges for this act. The Uganda Communications Commission could play a role in enforcing this by issuing strict rules and regulations. Indeed, the UCC twitter account recently alerted that whoever shall be using social media to meet or address a big number of participants must register with the media authorities to reduce the abuse and violation of people’s rights including inciting of conflict, hate speech and tribalism. 6

Beyond better monitoring of social media channels and individual awareness, interviewees suggested community-based solutions for violence and conflict.

Unity amongst leaders is a key factor towards bringing long lasting peace amongst the young generation. This can be done through regular meetings, exchange visits, and good conduct by all leaders to demonstrate love and unity toward each other. At the moment, we have Dinka churches, Nuer churches, Shuluk, and Moru churches separately. In one of the sermons, a community and church leader, Mr. Aleu, suggested there should be an extra church service added in a common language such as Arabic or English to combine all categories of people. The sermon was held in Bweyale South Sudanese Dinka church and was attended by 150 congregants, including children and the sermon ended in mixed reactions with ¾ of the church agreeing to the proposal while ¼ say language would be a very big challenge to a few of them.

Peacebuilding NGOs and the Ugandan government have focused on sensitization and awareness sessions to bring all tribes together. They must ensure that we are first of all safe, and the environment is as well as safe. These efforts often combine conflict resolution, peacebuilding, and economic empowerment. Peacebuilding partners such as Whitaker Peace and Development Initiative are empowering young people through conflict resolution education, and peace building activities such as sports, among other activities. Save the children, Transcultural Psychosocial Organization (T.P.O) and Danish Refugee Council (DRC) are mobilizing women and youths to engage in income-generating activities such as VSLA SAVINGS, trainings on hands on skills, and economic empowerment through monitoring and follow up of field supported business plans. Biar Dut, an influential Dinka leader, says this is a very good step taken by the implementing partners towards sustainable development of the local people.

Bringing people together to celebrate their different cultures is another way to reduce tension. In 2017, the Danish Refugee Council and the Government of Uganda organised a cultural gala where all tribes in the settlement showcased the beauty of their tribes, foods, traditional cloths and culture.

The Gala was followed by a series of peace marathons to strengthen the bond between the nationals and the refugee communities in the camp. The Marathons where organised trans-Bweyale to Panyadoli hills. It was from these marathons that the refugees got to realise that the nearby town of Bweyale is a potential place to venture in business and vice versa to the nationals—the settlement could be a place for them to expand their economic activity. Chatiem Matiop, a video advocate for peace, also remarked that the marathon also opened eyes to some of the locals that indeed, South Sudanese are not all violent and arrogant.

Empowering youths in both economic and social activities

We must teach children how to love while at their toddler ages to grow up with a mindset of love and unity. Already, there is evidence that programs targeting young people and linking economic and leadership opportunity with education and peacebuilding skills are proving effective. I spoke with some of these young people at International Youth Day. Aol Nancy, a 22-year old young woman and member of the Acholi people in Equatorial, said youths are the future of South Sudan’s tomorrow and therefore, they should not be involved in inter-tribal conflicts but rather engage in Peace building activities such sports. From her remarks she says she is interested in Peacebuilding Programs which focus on bringing many tribes in the settlement together.

The conflict that erupted in 2013 – 2014 has contributed to tribalism and conflict, but through the involvement of youth representatives the in peace process, it gives a great motivation and great achievement of a peaceful co-existence in Kiryandongo Refugees Settlement. Nancy believes that the youths are the future of tomorrow and to achieve this, we MUST stop tribalism, promote Justice and reconciliation, and implement youth advocacy through programs such as remembering the once we lost, united state institute for peace and South Sudan youths for peace and development who strengthens youths progress for on greater future to be good leaders.

On International Youth Day, I spoke with youths on matters of tribalism in the settlement.

Magong Andrew, a South Sudanese, Nuer by tribe from Unity State, Bentieu and a current youth leader in Bentieu expressed his experience on the recent war outbreak of 2013 and 16.

First and foremost, he outlines most of the negatives impacts such as loss of lives and property, which has left many people especially the children homeless and orphan, high rate of trauma scattered parents and disruption of education, poor health conditions where as well as observed.

He further added that the outbreak of this war has led to tribalism among various tribes, and as a youth leader in his community, he has come up with mechanism of teaching/facilitating community with phrases and slogans such as No to tribalism, No to racial, peaceful co-existence to embrace diversity, respect our culture and tradition, sharing school, churches, hospitals, worship places to be one people.

As a youth leader, he is taking part in youth activities such as sensitization, mobilization of fellow youths through giving voice to the voiceless, encouraging them to go to school, and have moral behaviors to transform lives of other youths. Through mediation, sports, peace and educative activities, approbation of other tribes, and teamwork, makes us the youth peaceful as we work toward a peaceful South Sudan in future.

A South Sudanese woman, Dinka Feminist, Diana Chol Tuet, age 18 years, from Jonglei State, said that a community leadership structure supported her, making it possible for her to do work advocating for the rights of girls and women. “I am a feminist, activist and an advocate for the rights of the girls. Advocate for the rights of the girls by raising voice of the girls through fighting early marriage, rape, teenage pregnancies in my community, I don’t want to see an unsafe environment for the girl child, tribalism is not safe for anybody but most especially to the vulnerable girl,” Diana said. Diana’s remarks highlight the different ways young people, and young women in particular, are impacted by tribalism. Young girls, who are already relatively more vulnerable, face greater risks from conflicts and tensions within the settlement

Conclusion

In the final analysis, tribalism has caused more harm than good to the youths as stated and compiled in the above findings. However, the youths can strengthen the stated challenge above by ensuring youths voices are heard through advocacy programs such as peace building sessions, activities such as football and netballs, cultural galas, peace and justice, healing trau

ma, mediation education through scholarships, supporting the disabled through teamwork.

ma, mediation education through scholarships, supporting the disabled through teamwork.

I have learnt that through giving the youths voices and chances to work together on various peacebuilding activities, they shall come up with a stronger and well-built strategies to make South Sudan a strong and a peaceful nation.

- World Bank, “Refugee Population by Country or Territory of Asylum,” (2020): https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SM.POP.REFG?locations=UG&view=chart. ↩

- Tessa Coggio, “Can Uganda’s Breakthrough Refugee-Hosting Model be Sustained?” Migration Policy Institute (2018): https://www.migrationpolicy.org/article/can-ugandas-breakthrough-refugee-hosting-model-be-sustained. ↩

- UNHCR, Uganda Refugee Response Monitoring: Settlement Fact Sheet: Kiryandongo (2018): https://reliefweb.int/sites/reliefweb.int/files/resources/66776.pdf. ↩

- For an example, see Thijs Van Laer, “Understanding Conflict Dynamics around Refugee Settlements in Northern Uganda,” International Refugee Rights Initiative (2019): http://refugee-rights.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/08/Understanding-conflict-dynamics-around-refugee-settlements-in-northern-Uganda-August-2019.pdf. ↩

- https://m.facebook.com/dengdinka1?lst=100003313580749%3A879270061%3A1600337133&refid=17&_ft_=mf_story_key.10163910261395062%3Atop_level_post_id.10163910261395062%3Atl_objid.10163910261395062%3Acontent_owner_id_new.879270061%3Athrowback_story_fbid.10163910261395062%3Aphoto_id.10163910261315062%3Astory_location.4%3Astory_attachment_style.photo%3Athid.879270061%3A306061129499414%3A2%3A0%3A1601535599%3A1896391926098916179&__tn__=C-Re ↩

- Uganda Communications Commission, twitter post (7 September 2020): https://twitter.com/UCC_ED/status/1303266498081886208?s=19. ↩