Man, if you knew what power you possess

When a thought in your mind, like a spark in a cloud,

Invisible, flashes, gathers the clouds

And creates fruitful rain, or thunder and storms;

If you knew that as soon as you kindle a thought,

Already waiting in silence, like the elements of thunder,

So wait your thoughts, Satan and angels:

Whether you strike into hell or shine into heaven;

And you, like a cloud, lofty but erring, wander,

And you yourself do not know where you fly, you yourself do not know what you do.

People! Each of you could, lonely, imprisoned,

With thought and faith topple and lift thrones!…

― Adam Mickiewicz, Forefathers’ Eve

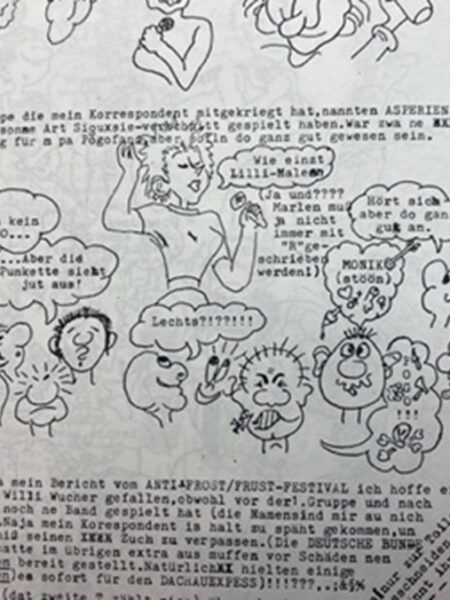

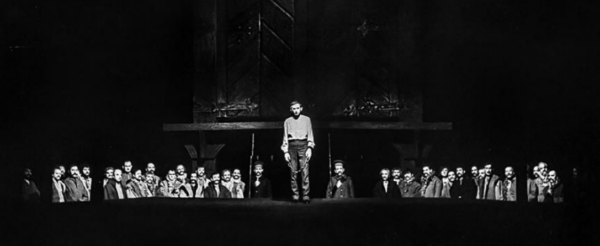

On January 30th 1968, Gustaw Holoubek entered the stage of the National Theatre in Warsaw to play Konrad for the last time. Not only will he not portray this character again in his life. No one in Poland will be allowed to do so for the next ten years.

“I remember that, um, first there was some scandal in the media, right?” was what one of the people I interviewed for the project said when I asked about 1968.

“B: Exactly, the newspapers wrote about it

J: Because apparently, at that show, there was the ambassador of the Soviet Union, right? Holoubek was apparently shaking chains…

B: Pointing at…

J: Pointing at the ambassador… and there was a commotion, right? That’s what I remember, and then there were some private conversations.

B: And they took it off the bill.

J: Completely…

B: And it was banned.”

Based on one of the most well-known Polish books, the play “Forefather’s Eve” was first shown in the National Theatre in Warsaw on November 25th, 1967. To explain the political situation we are entering better, I should quickly recall the “Forefathers’ Eve”. It is a drama written by Adam Mickiewicz, one of the most recognised Polish artists of the 19th century. The drama, written in 1832, recalls the events of 1823, when, among others, Mickiewicz and his friends were prosecuted and sent to exile for promoting anti-Russian ideas. The book depicts the lives of Polish people under Russian rule. The fact that Mickiewicz was allegedly conspiring to overthrow the regime in the 19th century didn’t help when the play took place in 1986 under the USSR’s communist rule.

Kazimierz Dejmek, the director of this particular staging, was lucky enough to present it on stage fourteen times before it was taken off the bill, not for the first time. As Kazimierz Braun, another Polish director who also directed the play (years later), said, the ability to stage “Forefather’s Eve” was constantly changing, corresponding with changes in the political background of Poland at the time.

In this project, I wanted to examine the possible connections between the censorship of the play and what is known in Poland as the events of March ‘68. A term used to describe a multi-faceted, hard-to-clearly-define socio-political crisis in Poland. The country experienced a series of student-led protests against censorship and the authoritarian policies of the communist government, which were met with a harsh crackdown by the authorities. This period also saw a state-sponsored anti-Semitic campaign, leading to the forced emigration of thousands of Polish Jews. Of course, I am well aware that there were other factors that sparked the riots across the country, but with my interest in theatre’s role in politics, I decided to focus on it.

As the events that I want to talk about happened 56 years ago (as for 2024), I needed to find the best primary source of information – the elderly. I managed to enter some retirement homes in Łódź and talk with older people from 66 to 90 years old (10 and 34 in 1968). The results of the interviews conducted were quite interesting. Some people confessed that at the time they had no idea about “Forefather’s Eve”. Some declared their interest in what was happening but were too young at the time to actively participate in riots. The oldest of the people I have talked with told me that they were, on the other hand, “too old”, that the students were the group who took the initiative, and that the working class was scared.

“They were simply afraid, afraid of the consequences, there was fear and that’s it.”

“I think that… older people were restrained, right?… They didn’t express themselves, they didn’t want to, because, you know, it was related to work and everything, so… everyone kept their mouth shut.”

With that, I should probably begin the story of the events of March ‘68 retold through the memories of my interviewees (most of them wanted their identities to be kept hidden, so I won’t be using names other than those of public figures from the time).

Some may say that students were not a big enough group to create a change, but one of my interlocutors noticed.

“It was essential because it showed that some part of society… a small one, wanted to achieve something, right?”

Right. It was very important. However, what I have found even more curious was the idea that one singular person could have set this whole thing into motion. Many people who I have worked with recalled the brave actions of one of the actors, Gustawa Holoubka, who shook the chains (a spectacle’s prop) on the stage directly in front of the USSR’s ambassador (a metaphor to show that the Polish people were still restricted and imprisoned in their own country), most probably leading to the censorship.

“He told them the truth! He told them the truth, he didn’t lie.”

Afterwards the play was censored, not only by the Russian ambassador to Poland but also by the First Secretary – Gomułka who, in many conversations I have held, was remembered as biased against the Jews (which was also another very prominent issue of that time). With that, the students rose.

“J: The whole thing… it could have been connected… and most of all… if I remember correctly, after those party statements, the students reacted, right? And the police treated them harshly, I remember, at Matejki (street in Lodz), there were those

B: Dormitories

J: Dormitories, we used to go there to watch, right, and the police…

B: Things were happening there!

J: The police were beating them, the riot police with those long batons, they were beating the students, not caring whether they were girls or boys.”

As one of the women I have talked with said, they wanted a better life, and that’s almost always the case with the young. They would not live in a heavily censored country. They wanted to be free to read Polish authors, to learn the true history (many of the people recalled the secret leaflets handed around their workplace with historical knowledge about the Katyn Crime and Ribbentrop-Molotov Pact), and to see the world that was not referred to as “The Rotten West” where people died on the streets, but, unfortunately despite their actions, none of that would happen. Not for the next twenty-five years at least.

“I remember when “Dziady” was on, the fences were painted and the youth sat on those fences, we used to go and watch, and the police chased us away… “

Most of my interviewees recalled the students acting up, in Łódź, especially around the University’s campus, commonly called Lumumbowo in the city. The memories were full of banners on fences, beatings, the curiosity of younger kids trying to see the commotion, chased away by the Milice and the dormitories blocked.

“In that student town, the militia or ZOMO (paramilitary police) would just drop in… I went there too… by ambulance… because an ambulance was needed.”

Some told me about the private conversations that they had with each other, quietly, afraid of the consequences. One man recalled hearing his parents speaking in German, so he could not understand. Those differences were also quite evident when I asked whether the citizens of Łódź were supporting the riots.

“But people supported the students… there on Lumumbowo, they were beaten… two or three of them apparently didn’t even get up”

“People supported the students”. That was what most of my interviewees said. Except, they didn’t, not publicly at least. And that is the sad truth of these events. Universities were turning their heads. They were left alone. Alone on the fences, alone beaten by the Milice, locked in their dormitories.

The party archives of the Łódź PZPR Committee preserved a letter to the authorities sent on those days to the editorial office of the Łódź press:

“[…] student youth made modest demands that trouble us and hurt us to the core […]. By what right did our children, whom we gave birth and raised in poverty, be beaten […] By what right do criminals claim to act on our behalf to condemn Poland’s best children? We, the workers, go hand in hand with the youth and will demand the punishment of all those who contributed to the detection of the bandits, as well as the removal of the government of the squires […]. Let us join the youth for the good of our Mickiewicz’s homeland, that is, ours; let’s join our youth whose blood was shed on the streets of Warsaw, Krakow and other cities. I kindly ask you to post my letter because you are not responsible for the content. Eugenia Wiszniewska.”

But the repressions installed by the authorities worked. By March, April, there were almost no voices in solidarity with students. Good thing that by the year 1980 most of the Polish population will join Solidarity.

“And I say… I didn’t really care, because I didn’t realise at all what was going on, but I remember my teacher… she, with tears in her eyes, in a roundabout way… told us that it was bad, that there were riots and that we should stay away from it.”

This story is the one that inspired me to examine this topic, the one about the teacher telling her 12-year-old students to keep away from whatever was happening and to not speak about the situation with anyone in fear of the consequences. In the world I am living in right now it all seemed so surreal, but somehow, a simple theatre play has turned into something so much more – a stance against the usurper.

In one of the group interviews that I had the pleasure of conducting after one of the women told the group that she had read “Forefather’s Eve” at her school, she was met with disbelief, and not with jealousy, but with some weird sense of longing. Something that young people today would probably not understand. I remember my class in high school when we had to confront the “Forefather’s Eve” and its obsolete language.

Some may say that it clearly shows that only the students were influenced by the censorship, but they weren’t the only ones. Somehow, everyone became involved between the whispers passed on school corridors, parents talking in German with each other, and the fliers describing Polish history given out secretly. That was one of the other questions that I asked. Why it was mainly students who decided to take the stance?

“There were no workers… I mean, there were many, but they were scared, the factories had 10, 12 thousand people… well, they were scared, someone might overhear you or something…”

I find it understandable. The fear of losing the job, the only source of money to take care of the family. What moved me was the story of one of the women’s relatives, who was involved in taking a stance involuntarily.

“My aunt also said… that they went out for a break… they didn’t even know what it was about, who was leading it, nothing. When they came back from the break, the machines were already turned off. Because my aunt worked in textiles and didn’t even know who was leading it, or what. Everyone just shouted that they weren’t working. And that was it”

Vanda Božić and Dragan Tančić say that theatre is a “mirror of all social, political and other phenomena and processes, in certain time and in certain places”. [Božić, Vanda, and Dragan Lj. Tančić. “POLITICS AND THEATER.” Баштина, no. 60 (January 1, 2023)] Is this the only reason why the censorship of the “Forefather’s Eve” led to all these events, or at least was somehow responsible for them? The play, according to all of the reports, wasn’t necessarily very political but became political, all thanks to the actions of Gustaw Holoubek and probably the presence of a political figure.

My conclusion would be that any play can become political to one specific person or a social group if they can find the representations of themselves in it. If it were to be, any play could acquire a political aspect just by being recognised as such by the viewers. So, in this case, “Dziady” will always hold a political value to them. It is a story about Poland, about Poles imprisoned. I don’t believe that there will come a time when it won’t be a crucial piece of literature for my history.

Except, can I now speak about theatre influencing the everyday life of Polish citizens? Should the whole institution be “to blame” for the actions of the actor? Maybe yes, for allowing the show to be staged, maybe no, because at first, it was never meant to be one of the most well-known political stances in Polish theatre. For me, it shows how even seemingly insignificant things can spark a fire that can light up the whole country.

But these events didn’t burn the whole country. Events of March ‘68 were extinguished by the end of the summer. “Forefather’s Eve” was still off the bill, and the communist party was still in power. Nothing changed. Tadeusz Walendowski, Jerzy Szczęsny, Brunon Kapala, Andrzej Makatrewicz, Kazimierz Sobotka, and Marian Matulewicz – leaders of the Lodz’s Students went on with their lives and the consequences of their actions. Rozalia Jarząbek, a maths teacher, who single-handedly defended the protesting youth, lost her job and died shortly after. That was all. They still deserve our gratitude.

“I think it was good that those students rose… if they hadn’t done it, then who?”

“But those students were brave”

“I think that… we were not a democracy, without a doubt… so every uprising, I don’t know if it was fully thought out, I can’t assess what human losses occurred because of it, right? But… every uprising… made someone aware of something, and… it was moving towards future liberation.”

“J: Everything was piling up, starting with Poznań in ’56. And it was slowly breaking. Then in ’67/’68, later ’70 in Gdańsk… Poznań, Cegielski, it all started to move…

B: So, kind of like an egg cracking.

J: Yes, in my opinion, yes.”