On March 8, 2015, I Am She Network[1] was born. The team that coordinated the establishment conference consisted of two: Nour Burhan and me, Ismail Alkhateeb. A hundred and eighty Syrian women from different backgrounds met and agreed upon a strategy to empower women towards meaningful political, economic, social, and cultural participation of women in order to realize peace, freedom, justice, representation, and transparency for all Syrians

During the past five years, the network’s groups, aka ‘peace circles’, were seeking to raise awareness among Syrian women regarding gender-based violence and systematic discrimination against women. Despite the restrictions imposed on civil society’s activities, I Am She’s women could achieve significant changes for thousands of women and girls in the communities whether inside or outside Syria.

Thanks to the survey on gender-based violence that I Am She has conducted in 2016, Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom (WILPF) could closely monitor the violations on Syrian women during the conflict[2].

Now, I Am She Network is five years old. I am more than proud to see my dearest project growing independent and powerful.

This network is not the only organization that is working in Syria. Indeed, more than 93 women organizations are active among Syrian communities inside and outside Syria. Nevertheless, the growing challenges impose greater efforts, and the injustice on women requires even more solidarity.

Since today’s challenges are an extension to yesterday’s problems, it is important to look at the changes that occurred, whether positive or negative, in order to understand the obstacles and appreciate the opportunities.

This research aims at presenting a narration of certain aspects of Syrian women’s lives to get a qualitative understanding of women’s realities, concerns and priorities as well as how those have been changing during the past three decades.

The research was undertaken in the form of semi-structured interviews and short-life-stories in order to obtain an oral history on women’s collective experiences, understanding and personalities. It also attempts at looking at their opinions and analysis on the most remarkable aspects during the past thirty years.

Although my paper does not speak for the whole spectrum of women in Syria, it is an attempt to represent samples of women from diverse cultural groups. After all, Syria is a culturally diverse country with different communities, and women’s struggle from all backgrounds brings them unified for: equality, justice and peace.

This paper attempts to identify the historical context of remarkable changes that occurred in various aspects through drawing a comparison between different generations.

Discrimination in Education: Women’s access to education correlates with the development of their status and indicates the improvement of gender awareness.

Economic Empowerment: Investing in increasing women’s economic independence paves the way for more equality in decision-making in all aspects.

Gender Awareness: The process of changing attitudes, behaviors and beliefs that reinforce gender inequality is crucial to encounter gender injustice.

Domestic Violence: There is a significant correlation between a society’s level of gender inequality and rates of domestic violence.

Child Marriage: The root cause of child marriage is gender inequality and it is sustained by social norms and religious beliefs which reinforce injustice towards women and girls.

Reproductive Health: Many of women’s reproductive health problems are consequences of discrimination and lack of power to decide whether and when to bear children. It is an indicator of whether women have authority over their bodies or not.

Interviewees’ Profiles

Heyam Almouli: A fifty-seven year old retired teacher, Heyam was born and raised in Salamieh, Syria. She studied at the Teacher Preparation Institute and started her career as a teacher at the age of twenty. Coming from an Ismaili family, she was brought up in a progressive community that promotes women’s rights and gender equality. She taught for more than thirty years in remote villages in Hama Governorate.

Heyam Almouli: A fifty-seven year old retired teacher, Heyam was born and raised in Salamieh, Syria. She studied at the Teacher Preparation Institute and started her career as a teacher at the age of twenty. Coming from an Ismaili family, she was brought up in a progressive community that promotes women’s rights and gender equality. She taught for more than thirty years in remote villages in Hama Governorate.

Rola Ibrahim: A forty-six year old sociologist, Rola was born and raised in Homs City, Syria. She studied sociology at Damascus University and graduated in 1999. She was brought up in a traditional family that belongs to the Murshidis minority. She has worked as GBV coordinator and psychological counselor with multiple organizations. She writes articles on gender issues and provides psychological support for GBV survivors.

Discrimination in Education

The Syrian government approved on the Convention on the Elimination of Forms of Discrimination (CEDAW) in 2002. This convention strongly recommends that girls and women’s right to education is a central obligation of States parties under the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women (the CEDAW Convention). Nevertheless, the barriers for girls’ education in Syria are beyond governmental strategies and the discrimination against their right to access education is primarily societal.

Luckily, some women took the lead in breaking the societal barriers during the eighties and the nineties. Those women paved the way for generations of Syrian girls to come to demand their rights in education.

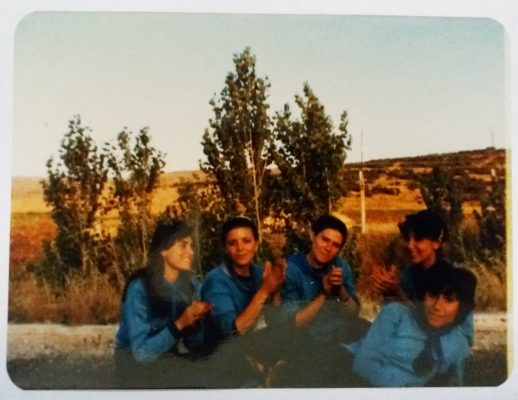

Heyam shared her experience in the eighties when she pursued her education after high school. In the first half of the 1980s, the vast majority of girls in Salamieh chose to become teachers through attending Teacher Preparation Institute in Hama. Such a decision was bound to societal factors such as: teaching is stereotypically the best career for women as they don’t have to work with men and they earn a good salary with limited working hours. Also, this institute is located in a nearby city, so girls from Salamieh don’t have to move away from their families’.

Nevertheless, few girls from this city had taken the initiative to challenge the traditions by moving to major distant cities such as Damascus or Aleppo to pursue their studies in some fields other than teaching. Because those girls were few back then, their stories went viral as pioneers for they have influenced many other girls.

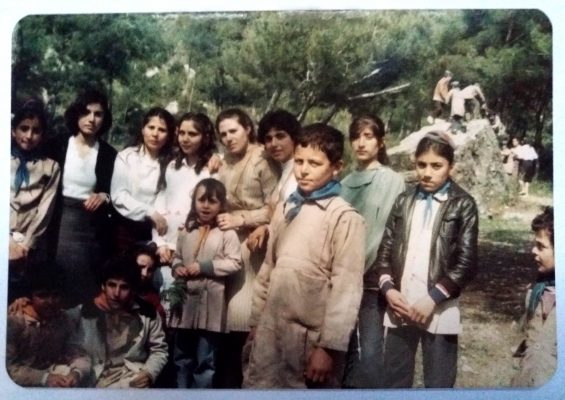

In 1994, Rola challenged her family and her society by moving from Homs to Damascus to pursue a degree in Sociology. In her case, it was not usual for an eighteen year old girl to leave her city to seek education on her own.

Rola: there were some things that I refused. I could get married in the tenth grade but I refused and this has caused me problems. I also had to pursue my studies in Homs but I refused and moved to Damascus and this has caused me problems.

Ismail: So what you did was unusual at that time even in your community.

Rola: Exactly, and this was a revolution that turned my life upside down but this also has opened the door for other women after that.

Rola mentioned that she observed notable changes during the first half of the 1990s as girls from more traditional communities started seeking further education.

Rola: The proportion of girls in universities has risen relatively. I used to see girls from Dara’a and other provinces coming to the university. Thus, this was a reasonable proportion in comparison with the past.

Nevertheless, those pioneer girls went through the same challenges as those who could not pursue their education.

Rola: The only difference is that the girls have a degree. Anything else involved the same type of suffering. I’ll give you an example: There was a girl from Al Jazeera (north east of Syria) studying medicine, her family called her and asked her to come back home immediately to get married, thus she left college in the third year. The gender awareness among the girls was low. Girls used to go to university for some reasons like higher education and dormitories were free. Regarding gender awareness, it was low.

Even though girls from all classes and communities in Syria faced the same type of oppression when seeking a higher education, such oppression was not equally distributed, especially among cultural groups.

For example, in Salamieh in the 1980s, the Ismailis community appreciated the importance of education for women prior to the other cultural groups as Sunni Muslims.

When I asked her about the difference in respecting women’s right to study among different cultural groups in Salamieh, Heyam said:

I noticed that the Ismaili community is aware of the importance of women’s education and work more than others. Other groups favored girls to get married at a young age rather than pursuing their education. Such was the case where we used to live. For example, in my family, all of us were girls who pursued their education and graduated. Whereas in our neighbourhood, the majority of girls got married at a young age. Those belong to a different cultural group (other than Ismailis). We, as Ismailis, never thought of getting married before graduating and completing our studies. It is because of what we have learned through observation ; that women who are not productive and economically unstable, their life quality is poor. This is where I personally stand on that.

The situation in Homs in the 1990s was not very different. Rola mentioned that girls from groups other than Sunni Muslims were more aware of their right to access education.

Ismail: In Homs city, where there is a cultural diversity, was there a common oppression in all cultural communities in Homs city?

Rola: Yes, but in an uneven way. We, who belong to non-sunni islam are more liberated. And the most liberated are the christian people (as girls). This is the general atmosphere back then.

Rola also mentioned that even high profile decision-makers have not taken women’s right to access higher education seriously.

Rola: I remember that one day a girl went to meet the rector of Damascus University in 2002 to ask him for a dormitory as she was pursuing a master’s degree. The rector answered her sarcastically: ‘go home and get married , that is much better for you!’

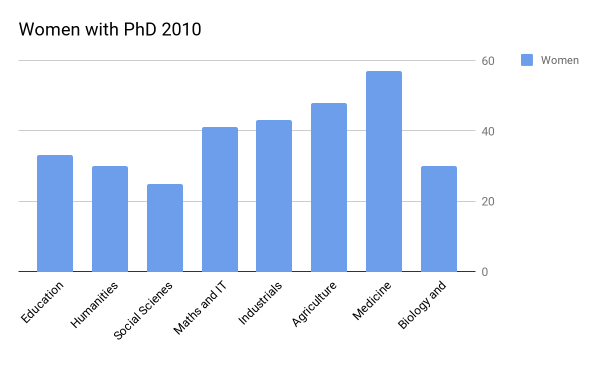

In 2010, there were 23 universities and 81 higher education institutes in Syria. Yet, women’s access to education after high school is heavily restricted to certain fields. The following chart shows women who earned PhD in different fields in the year 2010[3].

Indeed the above mentioned figures indicate a remarkable progress in terms of eliminating gender discrimination in education. This would not have been possible without women fighting their way up against the norms, the societal oppression and stereotypes. Unfortunately, this has not lasted after the breakout of the Syrian War in 2011, and it keeps getting worse every year.

The image of girls’ education, which started to get brighter until the year 2010, is getting darker again. The war that stormed Syria and caused a massive crisis of displacement and tremendous destruction in education facilities has affected Syrian girls the most.

The Syrian civil war has been distinguished by a brutal targeting of women. The United Nations has gathered evidence of systematic sexual assault of women and girls by combatants in Syria and describes rape as “a weapon of war”. For instance, terrorist radical groups such as the Islamic State (ISIL) have increased the brutal treatment and sexual enslavement of women and girls in the zone. Thus, security concerns make parents more reluctant to allow their daughters to travel long distances to attend school fearing for their lives and ‘honor’.

The net enrolment rate for primary education dropped from 92% in 2004 to 61% by 2013 (61.1% for female and 62.4% for male) and, for secondary education, from around 72% in 2009 to 44% in 2013 (43.8% for female and 44.3% for male)[4].

So it is that, aggravated by traditional gender roles and inequalities that cause parental prejudice against girls’ education, Syrian girls have ended up in a high risk of dropping out of school as one of the devastating consequences of conflict on the civilian population.[5]

Economic Empowerment

The Syrian legislator ensures women’s equal right to own property, run business on their own and initiate legal processes. According to the Syrian legal system, Syrian women have full and independent control over their income and assets, and they are free to enter into business. Nevertheless, the reality is not so bright. Women who own property via inheritance or through their own financial means may face social restrictions when attempting to make use of them independently. Also, women are not expected to save their income and use it for their own.

As a consequence, Syrian women don’t have the authority over their major life decisions including education choices, career, marriage, divorce etc.

Heyam mentioned that in her community, women started to realize the significance of women’s work and the importance of controlling their own income independently as a way to gain their rights, reject men’s domination over their lives and improve their quality of life.

Heyam: Out of what we have observed, women who are not productive and not economically independent have miserable lives. This is my personal point of view. Those women are devoted to their children, households and spouses. In addition, they suffer from oppression, persecution and deprivation of their right to be free. They are not free to move, they can’t speak their minds. In contrast, women who were raised to prioritize education and career, they postponed marriage till they are able to be economically independent.

This has changed during the nineties, as women were more free to move to other cities and choose the careers they like.

Heyam: People became more aware of the significance of women’s economic independence. Such was derived from the fact that women contribute more when they are economically independent, and also because it is human right to decide what they want to do with their lives.

When looking at women’s status in the rural areas, the situation has always been difficult. Women contribute to their households’ incomes through spending most of their time working in agriculture. Still, they do not own any shares of the property that they technically run, such as the farming land, animals or real estates. In case of divorce, women are left without any type of financial guarantee or other sources of income.

Heyam talked about women in the rural areas, specifically in the villages of Hama Governorate. There, women are given little freedom to go out, but apart from that, men dominate all aspects of life. In addition, women work in the farms, feed animals and do heavy agricultural labour. Still, they can not own any property or any shares in the farms where they work. In brief, women in rural areas are not treated as partners, but as labourers. In case of separation, those women can’t take care of their children anymore, as they lose their means of living. Therefore, they often leave their kids.

Heyam talked about the story of a woman in a village who left her four year-old daughter to her former husband, as she did not have any way to support herself in raising a child. Also, she mentioned the story of another woman who had to abandon her three children after she got divorced. Neither her nor her family could afford raising three children, despite the fact that she was totally supporting her household when she was married.

Rola also mentioned the findings of a survey she conducted in the countryside of Damascus while studying sociology. Women spent their time working on the farm and taking care of animals. Still, in comparison to what they contributed to their households’ economy, they owned nothing to support themselves if their spouses abandon them.

In the eighties, efforts were made to empower women in order to enable them to take control over their lives’ decisions and become economically independent and self-sufficient. Many women sought training and education to improve their careers. This was manifested in the fact that many women figures emerged as successful business women, influential managers and even ministers.

Rola talked about the changes that occurred during the 2000s. Syrian women became independent in comparison to the generations of the 1990s.

Rola: I remember many women in that period were successful: such as TV journalists with remarkable charisma. Also, many women proved to be high profile leaders of institutions and organizations. One of the factors that contributed to such developments is simply having child-care centres in their workplaces.

According to the Central Bureau of Statistics in Syria, women’s participation in the labour market only developed slightly between 2001 and 2010.

|

|

2001 | 2004 | 2006 | 2010 | ||||

| Male | Female | Male | Female | Male | Female | Male |

Female |

|

|

Employed (%) |

92.5 |

78.3 | 89.4 | 78.7 | 94.4 | 76.9 | 93.8 |

78 |

|

Unemployed (%) |

7.5 | 21.7 | 10.6 | 21.3 | 5.6 | 23.1 | 6.2 |

21.99 |

Source: The Central Bureau of Statistics in Syria (multiple years)

Likewise, women’s participation in different economic activities developed vaguely according to the Central Bureau of Statistics. This means that men are still largely dominating the labor market.

|

Year |

2001 | 2004 | 2006 |

2010 |

|

Agriculture (%) |

57 |

25.5 | 31.6 |

21.8 |

|

Services (%) |

31.6 |

56.3 | 52.5 |

57.7 |

|

Manufacture(%) |

6 | 7.7 | 7.9 |

8.9 |

|

Hospitality Industry (%) |

2.3 | 3.2 | 4.8 |

6.6 |

|

Transportation (%) |

1.1 | 1 | 1 |

1.6 |

|

Finance, real estate and insurance(%) |

1.1 | 1.9 | 1.6 |

2.9 |

|

Construction(%) |

0.9 | 4.4 | 0.6 |

0.5 |

Source: The Central Bureau of Statistics in Syria (multiple years)

Whether a woman works for a wage or not, she does not stop working at home. Probably, it is difficult to re-organize women’s roles to receive wages for housework. Still, it is important to give women their shares of what men traditionally possess. Likewise, as Rola mentioned, women do not have authority over their salaries no matter what their profession is and how much they earn, because every penny they earn goes to their spouses.[6]

Gender Awareness

Women in Syria, like many women all over the world, suffer from different forms of maltreatment. Many social factors contribute to normalizing such violent behavior towards women. In many cases, women seem to accept and deal with such types of behavior as social norms. One of these factors is a system of social values that consider women as inferior to men, that they should be guided and disciplined as a manifestation of control. This is mainly due to the pattern of family and social upbringing in society that perpetuates a kind of social acceptance of violence against women.

According to Heyam, she was raised up in a family that tried to break the pattern of normalizing discrimination against women. When I asked her how she started developing her awareness towards the cycle of gender injustice, she answered:

Heyam: This is thanks to my family and the way I was brought up. We observed in our neighborhood how girls were oppressed and had no rights or freedom at all. They were not even allowed to express themselves. Those families, like mine, realized that girls should be given the opportunity to be empowered before thinking of getting married. Unfortunately, this was not the case for all families.

For Rola, her family was normalizing discrimination based on the fact that she is a female.

“Ismail : When did you feel the difference in the gender roles in the family?

Rola: I felt like I was segregated. Plus, the phrase “because you are a girl (female)” was repeated over and over again. Because you are a girl you have to do this, you can’t stay late outside. Because you are a girl you can’t study outside Homs (in a different city). There was a long list of forbidden things.

Ismail: And was this during your middle school?

Rola: Yes. It was always repeated that “because you are a girl” you have to do housework. No going out and no staying out late.”

Nevertheless, she came to realize that such discrimination is not normal. This is thanks to a book she read during middle school.

“Rola: I read a book that has lit a lantern in my head and changed my mind. It is what drove me to gender awareness prior to all girls in my surrounding. It is “An Introduction to the Psychology of the Oppressed Man” by Mustapha Hejazi[7]. When I read it, I was in the tenth grade and it changed many things that used to be facts to me in terms of gender and women status. The book has a whole chapter about women. This is what granted me awareness before going to college.

Ismail: So you felt that you could see the gender differences?

Rola: Exactly.

Ismail: After you read this book and you gained awareness, how did you transfer this awareness to your personal and social life?

Rola: It has changed a lot. Also, There was another book, “An Introduction to Studying the Arab Society” by Hesham Sharabi[8]. I mean, there are social aspects, customs and social traditions that are needed in our lives and we need to live with them as they are. But after reading these two books, I gained a critical perspective at the women’s reality and I felt that the women’s status isn’t right. And this was reflected on me as I wasn’t a typical woman any more.”

Thanks to the gender awareness these two women have developed, they started to distinguish the various forms of injustice being inflicted on women in their community as well as other communities.

In her testimony, Heyam mentioned that she has observed even worse social injustice towards women when she left to teach in the rural area of Hama Governorate.

“Heyam: I have observed many social norms that led to the girls lacking self-confidence. The parental approach for upbringing girls made them think that whatever they do they are wrong. Even to express their opinions or to laugh was considered socially unacceptable.

In the villages, where I used to live to teach in the 1980s, the social norms were very different from my own community. Women there have some type of freedom to go out and have fun, but they were not given any essential freedom or value. Men were dominant and in possession of everything. Yet, only women who used to work in farming, taking care of animals and housework, still own nothing and can do nothing. Women were treated as farm workers not as partners. In case of separation, women had no assurance as they owned nothing. They even left their children behind as they could not support them.”

In fact, the situation in the 1980s regarding the rural women’s status has not improved twenty years after. Rola also shared her observations when she conducted a social study during her undergraduate years. This study surveyed women in the rural area of Damascus Governorate. She also came to the same conclusion as mentioned above.

“Rola: I have conducted research with a professor in Damascus City and the countryside of Damascus. The topic of the study was about the role of women and their social status. The study was based on a very well-designed questionnaire. We had samples from Damascus and the countryside of Damascus. This was in the year 2000 and the sample was pretty wide. with a very strict validation methodology. The results showed that women’s role is significant and it doesn’t fit with their social status at that time.

Ismail: Could you clarify what do you mean by ‘role’?

Rola: What she is doing. Simply, how she spends her time

She spends her day in housework, childcare and agricultural work, as we studied agricultural societies too. Also, some women do household repairs like (gas bottle installation), while these tasks are usually connected to men.

And this, in comparison with what she owns (like land) and she doesn’t own the delegated divorce right[9], means she owns nothing.

Ismail: So this research is extremely important as it showed that her productivity is much more than her social status. And my question here is: Is this situation justified in traditions and in law as well?

Rola : Not in the law relatively. But in family law status laws and in women-related laws: yes. But in fact, traditions are stronger than the laws.

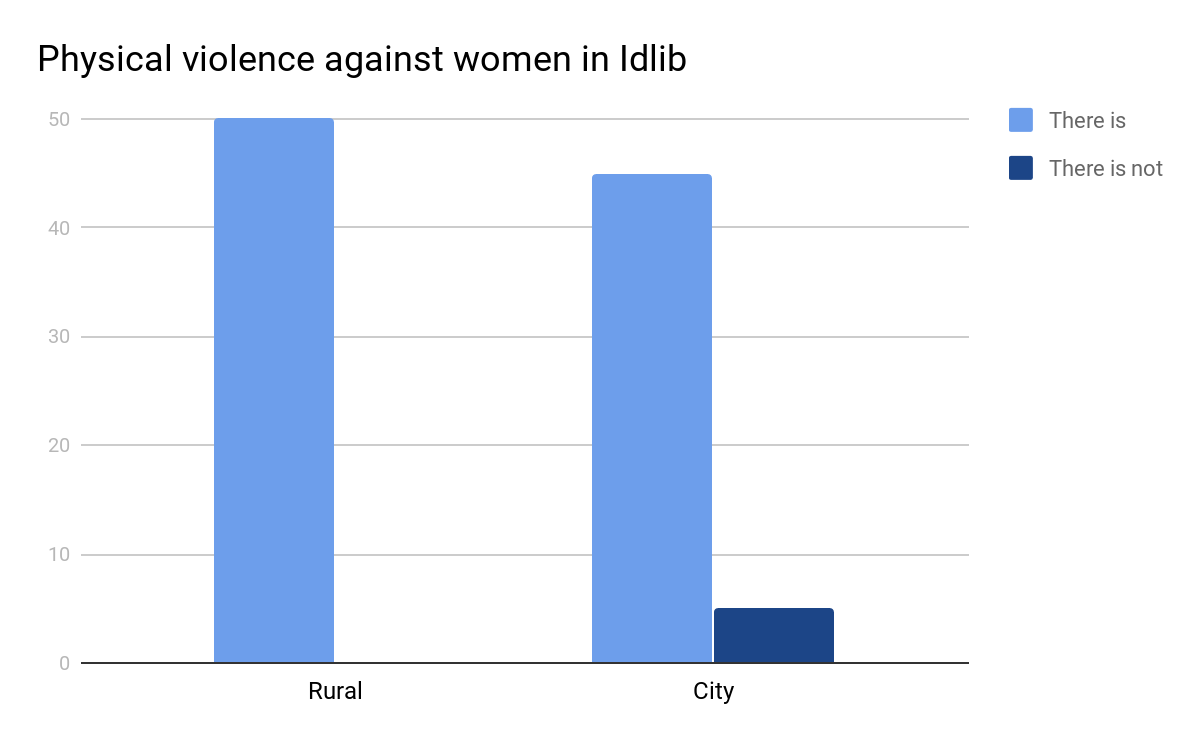

Even the Syrian Commission for Family Affairs’ report in 2014 stated that women in rural areas are far more exposed to gender-based violence and more frequently in comparison with women in urban areas[10].

As a sociologist, Rola believes that gender awareness in the Syrian society has not developed significantly and meaningfully. This conclusion is based on the fact that there is no plan on raising gender awareness on the national level. Plus, there is not a method to measure the development of gender awareness among the members of the Syrian society in general. Thus, the superficial aspect of women liberation such as modern clothes, smoking in public and engagement in the workplace can’t be true indicators of the meaning of liberation for Syrian women. Even field-based studies show that there has not been a significant development in the collective mentality towards women’s rights. However, social media can help slightly in observing some changes. Still, this can’t be a trustworthy method of measurement.

Domestic Violence

Domestic violence occurs between two people in a relationship. Domestic violence may take many forms, including emotional, sexual and physical abuse and threats of abuse. Abusive relationships always involve an imbalance of power and control. An abuser uses intimidating, hurtful words and behaviors to control his partner. This problem has always been hard to be spotted and tracked in Syria. Women often hesitate to speak up against their abusers who are most of the time their male siblings, husbands, boyfriends or fathers.

For instance, Heyam mentioned that during the 1990s, very few women could dare to speak up about being abused at home by their male family members or husbands.

Heyam: Many women have spoken in public about domestic violence. Only those women who could not carry on their marital lives with their spouses due to excessive violence. The majority of women kept silent and swallowed their families’ abuse and spouses’ violence just to maintain their marriage and household. Only when things get to the point of separation, those women would speak up. That was very common during the 1990s. Even in the 2000s, I could not notice any remarkable progress. Violence against women was not being spoken about in public. Nevertheless, divorce is becoming more common nowadays due to domestic violence. I am not sure what the reason is. It could be women’s awareness about the right to stop violence in their households, that is in particular after 2011. Such violence was considered a personal issue that should not be revealed. It was not considered normal, but she would compromise to save her marriage.

The normalization of domestic violence has led to many women suffering in silence. Heyam shared a story about one of her best friends who endured a long abusive marriage, despite the fact that she had a serious heart failure. This story left me speechless, so I had to stop recording for five minutes before I could resume the interview.

Heyam: I knew one of the victims who died after a long , abusive and miserable marriage, who died in the end. She endured her husband’s cruelty and violence so much. She was seriously ill, her heart was failing. She never spoke up about it, she kept silent for the sake of her children. She was not working as well. Her heart’s condition in addition to the abusive relationship led to her death young. She knew that it was not normal to be physically abused this way, but she never thought of seeking separation. Even her family let her down. This also has affected her children dramatically, even when they became grown-ups.

She also added that in this period of time, divorce bore a social stigma. Therefore, the majority of women hushed up about being abused at home just for avoiding divorce. Thus, many women were suffering harshly in silence. Those women who don’t have alternative sources of income or any properties tolerated so much violence rather than seeking separation.

The Syria Commission for Family Affairs surveyed 5000 women who are over 18 years old in 2014 [11]. The study’s report came to a conclusion that women are subjected to different and varied types of physical violence ranging from threatening, punching, slapping, kicking to using knives, belts, sticks and even rifles. For instance, over 45% of surveyed women said that they are being punched, slapped or kicked. Also, 16.3% of them mentioned that they were hit with objects that caused severe pain or led to a serious injury. When asked about by whom they were abused, 68% answered that it was the spouse.

Rola mentioned that between 2000 and 2010, gender based violence was referred at violence against women. Back then, speaking up about violence against women was unacceptable. It was particularly difficult to discuss this issue in the public media. This is why many women were exposed to constant domestic violence, still they have not spoken up about that . She added that until now there are many women who consider domestic violence normal.

Heyam agreed on the fact that domestic violence against women increased in the past few years after the war. She told me about an incident she has witnessed in Salamieh’s courthouse.

Heyam: I have met a young woman with her two daughters when she was in the process of delivering the children to her former husband to finalize a custody case. Although they were divorced, her former husband insulted and verbally abused her in front of the courthouse staff. Even though he is alien to her, he dared to abuse her.

This incident is a clear evidence that women’s status has not improved, so men still abuse women without any form of social or legal restrictions or consequences.

The most extreme form of domestic violence is represented in murder. One of these forms is murder with the motif of defending ‘honor’, also known as ‘honor crimes’. In fact, such form of crimes is socially hushed up about, and not considered legally as a first degree murder. The Syrian penal code still tolerate lenient sentences for murders committed in the name of “honour” despite a recent reform which brought increased penalties and abolished the possibility of complete vindication for certain “honour crimes”[12].

Heyam mentioned that there has been a period of time when many crimes occurred frequently. Nowadays, it seems to have decreased. But before that, many men killed their wives, daughters or sisters. Their sentences did not exceed ten or twelve years, which is not fair for such murders.

Civil society and feminist activists struggled, campaigned and advocated for reforming the Syrian penal code to eradicate the mitigating factor related to crimes labeled as ‘honor crimes’.

Rola talked about one of the many attempts to stiffen the penalty for such crimes and consider them as first degree murders.

Rola: in 2009, I was a member of the national team to protect children from violence. There wasn’t a significant amendment. And what is strange is that some influential figures like judges and clerics stood against changing it. And plenty of intense debates led to a secret vote. I think the ultimate decision was political. I don’t think that secularists are the ones who won. And there were rumors about fraud. The amendment was, instead of putting the convict in jail, the punishment became between a year and a half to three years. There was also an amendment in the Family Law but it was cancelled (out of nowhere) despite the great efforts made to achieve it. There were laws correlated to protect children from violence and family protection and women protection. And all of them failed . The only achievement was the one related to honour crimes.

She also mentioned that even high profile figures such as judges and academics opposed the project of ‘honor crimes’ law amendment. Those considered that such an amendment would lead to women breaking social norms. They did not consider this unfair law as a problem, but rather a ‘social guardian’.

After the war in 2011, domestic violence is reportedly on the rise. For instance, a field research conducted by I Am She Network showed that the majority of women in Idlib Governorate are subjected to physical violence , with a slight variation between the city and the rural areas.[13][14]

Child Marriage

Child marriage is not a new phenomenon in Syria. Prior to the Syrian civil war, 13% of Syrian women aged 20 to 25 were married before the age of 18. Conflict and disasters compound the pre-existing poverty, gender inequality and lack of education that cause child marriage to happen in the first place.

For example, Rola could have been forced to get married at the age of 15, if she had submitted to the social norms around her back then.

Heyam mentioned that in her surrounding , very few incidents of child marriage of thirteen or fourteen year-old girls occurred during the eighties and the nineties. Even in the rural areas, where she used to teach, child marriage was also rare. Girls were not allowed to get married young, before the age of fourteen.

After the war in 2011, child marriage increased dramatically in terms of age, geographical location and social class. While I was working as senior program coordinator for Women for the Future of Syria[15], I contributed to conducting a qualitative study on child marriage in the Syria IDPs camps in the north of Syria. The research adopted two main tools, namely: focus group discussions that targeted 59 persons (26 women and 33 men) in three major camps; and in-depth interviews which were carried out with ten under-aged girls who experienced child marriage. The study came to several conclusions, among which are:

- Most girls married willingly and were not forced by decision-makers at home. Nevertheless, most of them were not aware of the dangerous health, psychological and social consequences of getting married at this young age.

- Most of them stated that they did not receive any type of support from their families nor from their spouses after marriage.

| The psychological consequences for CEFM, as gathered in the answers of the research sample[16] | ||

|

|

Yes |

No |

|

Feelings of isolation |

10 |

2 |

|

Feelings of permanent restlessness |

9 |

3 |

| Loss of the ability to enjoy activities |

11 |

1 |

| Decreased ability to achieve |

9 |

3 |

| Lack of independence |

7 |

5 |

|

Feeling safe |

7 |

5 |

Heyam also mentioned that after the war, she heard about cases of girls who got married at the age of 13 and 14. She considered this as a major backslide of women’s status even in comparison to the 1980s and 1990s.

In 2019, The Syrian Parliament has approved amendments to the Status Law, whereby the legal marriage age is set at 18 years and the age below is criminalized. However, given that a high percentage of marriage contracts that are not registered in the courts are performed on underage girls, which reached 60% in 2016, the problem remains more social than purely legal.

Reproductive Healthcare

Reproductive healthcare is closely related to gender-violence as women, it is an indicator that women don’t have authority over their own bodies.

In fact, violence against women or even the threat of violence is manifested in the fact many women to don’t have the ability to control their own reproductive health and to plan their own families. Likewise, women who experience emotional or physical violence or other forms of abuse within their relationships may also have less ability to negotiate the use of condoms or other contraceptives with their partner in order to protect themselves from these outcomes. Also the stigma related to abortion remains one of the most dangerous forms of gender-based violence as it leads to many women losing their lives during pregnancy.

Heyam talked about the 1970s when birth control was unheard of in the environment she grew up in. Women’s role was to bear children as long as they can, regardless if it is willingful or not.

Heyam: During the 1970s, birth control was not heard of at all in the community I grew up in. As long as they are fertile and can bear children, they keep on doing so. There were no ways to control this or even awareness regarding this matter. Sometimes, they gave birth to up to ten or twelve children. They were not aware of the health risk on the mother’s body or the child’s.

Women had no right to say whether they are willing to get pregnant or not.

Also, she mentioned that abortion was a taboo, except when the pregnancy may threat the mother’s life. Apart from that, abortion was generally rejected and considered as socially prohibited.

The problem of no-birth control was among all social classes and cultural groups, according to Heyam. She added that as birth control methods were not available at all during that period of time.

During the 1980s, there has been a change, as health centres started raising awareness on family planning, and birth control methods as pills and helix contraception.

Heyam: in the beginning of the 1980s, things started to change as contraceptives became available. Also, because women started to participate in the labour market, they needed to plan their families and economize on having children.

During the second half of the 1980s and throughout the 1990s, the Syrian government, in cooperation with The UN Population Fund, launched a project for reproductive Health. This has led to positive changes regarding family planning and women’s reproductive health.

Heyam: The family size decreased due to the fact that women became aware of the risky consequences of repetitive pregnancies. Also, women needed to control birth as they started focusing more on their careers. Well, health comes first. So, they became aware that they need to maintain their well-being. Contraceptives became available along with raising awareness campaigns on family planning.

Before those changes occurred, women did not have the sense of ownership on their bodies. Also, they were ‘indoctrinated’ by the social norms that their duty after marriage is bearing children as long as they are capable. However, the 1980s brought significant changes as women prioritized their own well-being and then decided when to get pregnant. Throughout the 1990s and 2000s, reproductive health became an essential part of every woman’s life that they wouldn’t compromise on.

Statistics show that maternal morbidity decreased in 2004, as there were 58 cases out of every 100 000 live births in comparison with the year 2001, when the rate was almost 65.4 out of every 100 000 live births. Also, in 2004, newborn morbidity was 3.1٪[17]

After the war that started in Syria in 2011, the situation of reproductive health started to collapse dramatically. For instance, several studies have shown that there are reduced use of contraceptives, menstrual irregularity, unplanned pregnancies, preterm birth, and infant morbidity[18].

Rola talked about her observations in IDPs camps and shelters when she was providing psychological support to displaced women there. When she interviewed women who recently gave birth, they bear children so their spouses don’t abandon them. Others said that they give many children hoping that probably one of them may help in improving the household financially in the future[19].

Heyam mentioned that in some communities, using contraceptives is religiously prohibited. Therefore, the phenomena of lack of awareness regarding reproductive health ,that started to resurface after war, existed before the war in many communities in Syria.

Heyam: In some remote villages, families don’t practice any type of family planning, so the family size is still big. Mostly, the reason for not using contraceptives is religious. In other cases, it is the lack of awareness or the inaccessibility to healthcare that prevents women from practicing birth control. In addition, due to repetitive pregnancies, there are many infant morbidity and abortions due to health complications.

She also added that women in such remote villages may go through abortion by themselves or by unspecialized midwives, regardless the risks of having abortion without antibiotics or sterilizers.

Rola also talked about the role that the General Union of Syrian Women played during the 1990s in campaigning for family planning. They attempted to raise awareness on the significance of birth control in order to practice effective family planning. Nevertheless, they encountered opposition in some areas. She mentioned that a centre in Dara’a was vandalized as people considered family planning and birth control as religious taboos.

Syrian law restricts the granting of abortion in the Practice of Medical Professions Law, which stipulates that a doctor or a midwife shall be prohibited from performing an abortion, by any means, unless the continuation of pregnancy is a threat to the life of the woman[20]. Also, it does not exclude the cases where girls have been raped, according to articles 525–532 of the penal code.

Heyam: health centres and practitioners refuse to provide abortion without any medical causes, because it is considered as a crime. Nevertheless, women still seek abortion illegally and secretly without specialized supervision. In fact, abortion is legally rejected, but it is not socially denied. Therefore, many abortions happen behind closed doors.

She also added that there are no rehabilitation programs for women who have received abortion recently in healthcentres.

Rola believes that women’s ownership over their body is essential , and women only can decide whether to get pregnant, give birth or have abortion. She also added that women who have abortion bear the sense of shame, even if they are married.

Heyam: During the 1970s, there has been a widespread misconception that women are responsible for determining the child’s gender. Therefore, women were being blamed for bearing female children, as the society favors male children over females. So, women felt frustrated and guilty. In this case, women kept getting pregnant until they gave birth to a male child. Even during the 1980s, this issue remained despite the development of awareness. This also has continued throughout the 1980s up to the beginning of the 1990s. Many families had more than five female children until they could have a male, but when it did not happen, they stopped trying when the women could not bear children anymore. Some of these women were highly educated, and they know that the man is biologically responsible for determining the child’s gender, still they submitted to social pressure.

She also added that during this period, women lacked control over their bodies. Nevertheless, afterwards, women became more aware, so they paid more attention to family planning regardless of the child’s gender.

Conclusion

As this research paper has demonstrated, the lives of Syrian women have changed in all aspects in the course of the last four decades. Some aspects have developed radically, like education and child marriage, and this has affected the lives of women from all generations and cultural backgrounds. Other aspects have insignificantly changed, such as gender awareness and economic empowerment, due to various social factors. Nevertheless, women became more aware of the gender inequality they are subjected to in different forms.

The war that broke out in 2011, along with the rise of religious radicalism and the superiority of norms over the law have cause major deterioration in terms of domestic violence, child marriage, women and girls’ access to education, reproductive health and others.

Annex

References

[1] I Am She” is a network of community-based women’s groups or “peace circles” led by Syrian women, working to reinforce effective political, economic, social, and cultural participation of women in order to realize peace, freedom, justice, representation, and transparency for all Syrians https://www.ccsd.ngo/i-am-she-network-in-the-eyes-of-its/

[2] Violations Against Women In Syria And The Disproportionate Impact Of The Conflict On Them: NGO Summary Report for the Universal Periodic Review of Syria , WILPF, November 2016 https://www.wilpf.org/report-release-violations-against-women-in-syria-and-the-disproportionate-impact-of-the-conflict-on-them-ngo-summary-report-for-the-universal-periodic-review-of-syria/

[3] Euro-Mediterranean research cooperation on gender and science: Syria National Report, 2014

[4] Loss of Access to Education Puts Well-being of Syrian Girls at Risk. Marta Guasp Teschendorff United Nations University, September 2015.

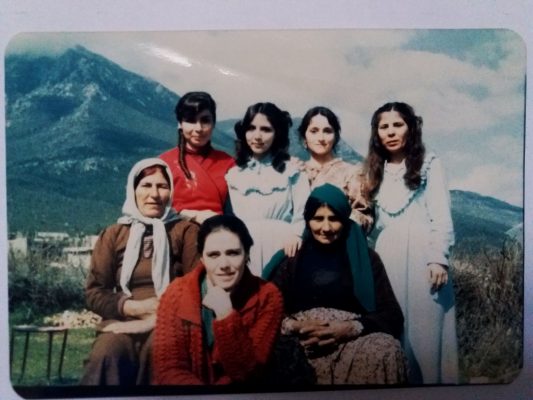

[5] Source: Heyam’s personal Archive

[6] Source: Heyam’s personal archive

[7] Social Backwardness: An Introduction to the Psychology of the Oppressed Man, Mustapha Hejazi.

[8] Neopatriarchy: A Theory of Distorted Change in Arab Society, Hisham Sharabi. 1992

[9] Delegated divorce: In Islam a husband can delegate the right of divorce to his wife or any third person (www.newageislam.com)

[10] The Syrian Commission for Family Affairs’ Study on Domestic Violence (http://musawasyr.org/?p=1134)

[11] The Syrian Commission for Family Affairs’ Study on Domestic Violence (http://musawasyr.org/?p=1134)

[12] Syria: MENA Gender Equality Profile. Unicef .October 2011 https://www.unicef.org/gender/files/Syria-Gender-Eqaulity-Profile-2011.pdf

[13] The Impact of War on Syrian Women, I Am She Network, 2018 The Impact of War on Syrian Women

[14] Source: I Am She Network archive

[15] Lost Childhood, Child , Early and Forced Marriage in Syrian IDP camps: Causes and Effects. Centre for Civil Society and Democracy (CCSD), February 2016 https://www.ccsd.ngo/lost-childhood/

[16] Ibid, p16.

[17] Reproductive Health in Syria: Increase in Birth and Decrease in Morbidity, Dr.Rim Duhman. http://musawasyr.org/?p=2418

[18] Women’s Health Services Lacking for Syrian Refugees, Syrian American Medical Society February 14, 2019 https://www.sams-usa.net/2019/02/14/womens-health-services-lacking-for-syrian-refugees/

[19] The Other Dimension of Motherhood in Camps, Rola Ibrahim, February 6, 2020 https://swnsyria.org/?p=12155

[20] Practice of Medical Professions Law, Legislative Decree No. 12 of 1970, Art. 47(B)

whoah this blog is wonderful i really like reading your articles. Keep up the great paintings! You realize, a lot of people are hunting round for this info, you could help them greatly.

I am very happy about your comments. I will be glad to contribute to any research needed on this domain.