1. Introduction

Roma are the biggest world minority that one can meet almost in any country around the globe; although the current situation is gradually improving, the life and history of Roma has been full of misconceptions and prejudices. My paper is devoted to Roma early professions because I would like to find out what influenced the life decisions of Roma people in the beginning of the 20th c. Why they engaged only in a limited number of activities which still were hard choices for most, and how these ventures created stereotypes and resulted in social and economic exclusion. This understanding should help my readers to discover today’s stereotypes surrounding the professions of the Roma minority, and I dare to assume those have been shaping the Roma lifestyle too, so this could tell something new to Roma about themselves.

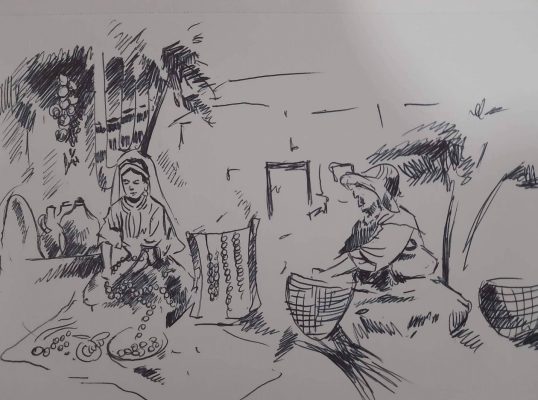

Broadly speaking, my research aims to challenge stereotypes and prejudices around the Roma population across the world in general and in Albania in particular. First, it would create a clearer understanding of the Roma history and professions. Second and therefore, it would help separate what originates in culture of the people and what was forcefully embraced due to their poverty and other challenging circumstances. Third, my research would connect Roma’s past to current social and economic situation, so that the stigma of lazy, unorthodoxly living nomads could be deconstructed through the lens of Roma’s actual hard work. Additionally, I collaborated with a young Roma painter whose name is Oktavio Kazanxhiu, who illustrated my paper with beautiful picture to make it more appealing to a broad public.

The early Roma history is reconstructed according to several hypotheses which are hard to corroborate in detail. This uncertain period spans their initial departure from the northwest of India to the middle-east and a long journey to Europe. Theories on Roma’s origins and distant past also include events that were scarcely documented in traditional historical sources. As a result, I encountered a number of challenges putting together the historical context for my topic. There are few primary sources to reconstruct Roma history. Even the analysis of interviews, available today as a result of my and similar studies, requires informed perspective, otherwise, it can either reinforce stereotypes or diminish the cultural and identity aspects of the Roma minority. Similarly, I must note the lack of secondary sources, existing few are often out of context, misused, or miss recorded by historians. Finally, there are limitations to coming up with a general argument and storyline as I am focusing on a period restricting the diversity of available professions.

2. Methodology

My paper begins in a more distant past and leads the reader towards the present. On this way, benefiting from the oral history method, I quote my interviewees to contrast them with the historical data and modern perceptions. Since the primary sources on the topic of early Romani professions were almost non-existent, I organized interviews with people who could recall or reconstruct the data about professions of their ancestors dating back to 1900–1945. To prove whether my research plan is feasible, I interviewed a senior lady from Pogradec, and then a senior longstanding Roma activist and artist. As the first interviews were successful, I reached out to the first interviewee again. I consider my method as fruitful because the active seniors travelling a lot during their lives witnessing rich data; furthermore, they have extensive social connections all over Albania. Additionally, I provide several viewpoints on the topic from the literature coming from international authors and scholars. It is crucial to have a broad overview of the country’s historical, social, economic traditions and customs. Then, I explain in more detail which contexts led specific Roma groups to practicing specific professions. I hypothesize that certain low-paid, hazardous professions were imposed on the Roma because of their ethnicity.

3. Historical overview of four key periods

- Roma origin and early immigration from India

According to historical and philological studies, Roma used to live in India one Aeon ago. Unfortunately, no one can provide a solid explanation to why Roma moved away from the continent. First two hypotheses agree that Roma fled due to famine or war. The third hypothesis comes from the “Shahnameh,” the book of kings, written in 1011, that mentions travelling groups of service professionals from India to the West. It suggests that Roma’s contact with the rest of the population was due to economic reasons. So, Roma as it also happens today were taking itinerant occupations in the service sector, mainly in metal work and entertainment. They were excluded from society having with it only economic relations. Up to nowadays, in India, nomadic groups of people work in various handicrafts, such as blacksmithing, basket weaving, knacking, dancing and playing music. This might be another argument confirming the origins of Roma in the region. However, moving from it, Roma possibly acquired the skills of trade and breeding animals. Yet this has never been Roma’s exclusive thing; additionally, scholarship testifies that the Indian ancestors of Roma also served as warriors and scholars.

This historical data confirms that all people cannot be naturally prone to a single occupation or lifestyle as some extreme scholars and politicians suggest. Given the proper environment and opportunities, people thrive in any skills and profession. Now, I invite you on a vivid journey for the later history of Roma professions. The first, brief stop is in the Byzantine/Ottoman Empire, within which Albania spent 500 years. The second stop is in the period lasting from the independence of Albania from the Ottoman Empire (1912) into the harsh Communist era.

- Accounts of Roma in the Byzantine Empire

According to the chronicles and other sources, the Roma in the Ottoman Empire worked in a range of professions. The tax registry of 1522–1523 mentions “gypsies” (a slur that since 1971 is internationally substituted with “Roma”) as military or freelance musicians (Roma History Factsheets). There is another evidence of Roma assembling with dancers, some of whom were Jewish women. In many countries where Roma have travelled to and settled, they are known as fine blacksmiths. Such an occupation has a long tradition and has been well preserved in the Balkans from generation to generation till today. Depending on the economic and political system, Roma could give up their former occupations, usually the ones in service delivery and trading, and become involved in agriculture which they practiced within the framework of existing feudal possessions of military officers.

- The Roma professions in Albania from 1912 to 1945

The precise moment when the first Roma families settled in Albania is unknown, however, Roma scholars believe that it happened around 600 years ago, which is connected to the close relationship of Albania and the Byzantium. In order to prevent uprises, the Ottoman empire moved its population around its conquered territories, this principle coexisted with the freedom of movement within the imperial territories, therefore the opportunity of trading goods and providing services and entertainment existed for Roma. However, with the First World War, the freedom of movement was limited, mainly for Roma, who used to breed and trade horses from cities in the southwest part of today Montenegro to villages in Greece. In 1913, when the borders of Albania had been firmly established, hundreds of Roma families ended up either within Albania or in neighbouring countries.

To corroborate the contextual information, I use the interview with Mr Kujtim Likzelia, a longstanding Roma activist and artist. Also, I summarize the stories that my maternal grandparents used to tell me. Before interviewing Kujtim, I introduced him to historical timelines and how different periods influenced Roma professions. We discussed the period of communism, and the common professions Roma practised, preferred or were free to exercise. We walked into the period of King Zog during the Republic and Kingdom regime, 1922–1939. Since Kujtim did not yet witness that period, I asked him to recall memories and stories from his parents or grandparents, which he remembered in a great number. He was curious about the war and the Italian soldiers wondering if they came to Albania to help or just to be here first before Nazis? His grandmother mentioned their good relationships with the Italians.

“Here, at administrative Unit 11 in Tirana, there is a river. Our ancestors used to wash the Italian clothes at the river, and they were paid with money or with baskets with soap. Our river here was a source of life and work. It has helped us a lot,” says Kujtim. He recalls that time as unbearable for his parents. They had to endure severe famine. “They could not find bread. My parents raised me with “Triska” [ration coupons]. I was a little child, but my father kept repeating how rough that time was and how he had to raise me. Our family was small, me, my sister and our parents. But I also had uncles and grandparents that made us an extended family.

My maternal grandfather, Gani Arbiti, a natural child of an Albanian landowner, recounted details from those “dark years,” in his words. He was raised by a single mother; they were forced to wander in villages asking for help to survive the famine. “Most of the villagers, notwithstanding the famine, were benevolent. They would share food with those in need”, was saying my dear grandfather. He and his mother used to travel from North to South of Albania. They met many people and witnessed bizarre stories, one of which was a blood feud between two northern families, which, unfortunately, remains a concerning issue up to today. Hundreds of families in the north of Albania are forced to hide indoors due to the threat of vengeance (Taylor, 2022).

Kujtim recalls that Roma hanged out with non-Roma because they were all in the same boat. Although Roma were traders, they could not commit much to trade due to the war; besides, it was also forbidden. Kujtim proudly states that Roma’s profession was selling horses and goods: in those years, they bred horses than trading them and clothes, passing this occupation through generations. Nowadays, the business of horse trading has almost perished. Only in Korça, it is still practiced; there is a marketplace where Roma bring horses. Tirana has no particular marketplace, although before, it was a point from where goods and services spread all over Albania. Kujtim recalls some names of famous blacksmiths and traders who made their living out of these professions.

Roma horse breeders, says Kujtim, knew well how to work with horseshoes. “Roma were masters in doing it!” The Egyptian minority settled historically in the Balkan and used to also forge horseshoes. They were masters in making axes, saws, hooks, pick-axes, horse-brakes, and crafted horse and donkey saddles. It was an in-demand product, which also many Roma elders carved themselves. I want to compliment the above information by bringing another interview I had with the old lady from Pogradec. According to her, Roma practiced a few professions, among which horse breeding and trading were believed to be exclusively for Roma. She recalls that her ancestors used to buy horses in the north of Albania and, after taking reasonable care, would sell them on the borders with Greece. Kujtim and the old lady from Pogradec agree that Roma were the best professionals in such a venture. They could recognize the age and condition of a horse effortlessly. The lady from Pogradec says that most of the Roma settled in one place like most do nowadays; they made a living as farmers, growing veggies and cattle. During the Communist era, Roma farmers had to work in the field like others. Grouped in small brigades they would grow veggies for the Albanian military forces positioned on the borders with Greece. She recalls, “The soldiers from the other side [Greek patrols] would insult and provoke us. We were advised by the Albanians patrol not to engage in arguments but focus on farming.”

Kujtim remembers that the Roma blacksmiths did not want to disclose their secrets and skills to others. Not only was it a profitable profession but also a social status. I followed up asking about the baskets made from river birch as this activity is considered one of the earliest Roma professions. However, in order to follow the timeline, let us move to the Communist era in which such activity was organized by the government and for which Roma played the central role.

- The Roma professions in Albania from 1945 to 1990

A turning point in the professional life of Roma was the instalment of the Communist regime right after the Second World War. In a conversation with my maternal grandmother a few years ago, regarding Roma ventures, she said, “Roma kept wandering around Albania for trade. But the regime of Enver Hoxha initiated a restriction policy, and whoever did not obey was segregated in remote villages and forced to any jobs the one-party system would decide.” The system prompted artisans and blacksmiths to work in cooperatives instead of being full-time freelancers. Kujtim Likzelia recalls, “A few Roma artisans were grouped to work at “Gjergj Dimitrov,” an old farm assigned to craft baskets. A brigade of Roma was formed. Their task was to produce baskets for harvesting ripped grapes in the area known as Paskuqan in Tirana”. Those flexible birch baskets could protect grapes during the transportation. He continues, “The Roma people were among the fewest to master such skill. They would select wild birch from the river and craft the baskets requested by the communist system. Indeed, it was one of the earliest professions Roma inherited and passed through generations.” Nowadays, it is preserved in Elbasan and a little bit in Korça. Handicraft of basket is among the three earliest professions. He adds, “while the Roma women used to make and sell hand-made accessories, Roma men generally used to breed horses trading them and accompanying accessories”.

Kujtim and I moved to another labour sector perceived through stereotypes. Entertainment and music are also considered Roma early or even the earliest professions. Parties and important family celebrations like weddings and birthdays were catered with Roma entertainers. Yet, another unorthodox venture was breeding bears for street shows. From his elders, Kujtim remembers a story of two Roma men that used to perform with a domesticated bear. “These two entertainers-animal trainers-had chained their bears through the nose. Animal trainers carried a typical backpack that only they would have, which was sewed and decorated differently. Inside, there was some water and food. It was a part of their uniform and a sign for the public to donate food or goods. They would even visit you at home. Once they were inside the yard, they would make the bear dance by giving commands,” says Kujtim. The bear would mimic vocally and visually a young lady on the beach or a young bride after an argument with her mother-in-law. The animal was intelligent enough to follow human instructions, although unable to communicate or understand the human language. “They were domesticated animals. He, the Roma person, could tame the animals and make them play his game. He would even play the drum and sing a famous Albanian folk song, “Xhinxhile moj Xhinxhile.” The bear started dancing immediately, holding the stick in his paws. Why would they use a bear?” – Kujtim rightfully questions himself. As he recalls, the Roma elders considered bears to have curative massage abilities. The bear would massage the back of a lay person with his hairy big paws, and afterwards, that person would feel relaxed. The elders used to say “massage from a bear sends away the fever.” “But, how is it possible that a two-tons bear would massage a lying person without squishing intestines?” – wondered Kujtim. He witnessed one occasion at his 200 years-old home and states the bear massage was light as a tree leaf. “Maybe the massage was overrated, or the healing was a psychological effect. However, it was extraordinary for us at that time!” – says Kujtim.

I could not continue my interview without asking Kujtim about the relationship between the Roma man and the bear. “When the bear did not obey, it would receive only a menacing look or commanding sounds from his owner warning about the consequences of disobedience.” However, Kujtim noted that bears were not maltreated by their humans, nor were they violent or aggressive. Roma entertainers were free to walk around with them in the streets. People would call them “a tall Roma with a pair of a moustache.” Kujtim remembers only two Roma men doing such a job. Roma sympathized to animals, especially horses: “I can say that Roma considers them part of the family, an important source of income. They would never maltreat an animal because it would infuriate them and misbehave during the show in the case of a bear or in the buyer’s home for horses,” says Kujtim.

Next, we discussed music. Kujtim claims that music is “life” as it makes everyone feel it and move along the rhythm regardless of the genre. “I am a dancer and I begin mimicking dance moves immediately after listening to music. But what is Roma music and who are Roma musicians?” Then, he continues, “Roma musicians are creators. Many dances or music are not recorded. Perhaps their authors did not know how to write and could be the Roma contributors. The Roma musicians represented Albania even beyond its borders.” Kujtim mentioned a few names of famous Roma musicians who sadly are not praised or acknowledged by the Albanian public institutions for their contributions (clarinetist Hekuran Xhambali (Xhambazi) and Kujtim himself). During the communist regime, Kujtim Likzelia participated in a dancer crew and after the regime contributed as an activist for Roma-related issues for 28 years. I should mention that surprisingly a few days after this interview, Mr Hekuran Xhambali received an award from the president of the Republic, Mr Ilir Meta, for his contribution to music. Kujtim says that Roma were natural-born musicians who lacked formal education in music. Regardless of such disadvantages, they would rarely make technical mistakes while playing instruments, and they would easily spot mistakes of other non-Roma musicians. He remembers that the drum was a key instrument for creating rhythm. Every group of musicians had someone playing the drum, a piece of ring-shaped wood covered by a piece of animal leather. It was widely used in weddings and other joyful celebrations to accompany rhythmic melodies and dancing.

I could not wait but ask Kujtim how the Roma musician managed to reach the weddings in distant areas and villages. Kujtim mentioned a Çajupi Theater and the Tirana Circus, which functioned as “markets” where musicians and artists would gather to pick up weddings. Those interested in their services would meet directly with the group they wanted to hire. Kujtim recalls that they would discuss it over a coffee and then reach an agreement. A person in charge of the wedding would arrange logistics and pay deposit. Usually, musicians and artists used the truck of the cooperative unit. Roma and non-Roma learned greatly from each other in the sphere of music. “Sadly, there is no Roma art in Albania. Although after the 90s, Mr Marcel Courthiade, a Roma-French linguist, attempted to enrich the Roma art, culture and music and even established an artistic Roma group and a music album, there are no initiatives, centres or well-established artistic groups to preserve the Roma legacy in music and dancing,” says Kujtim. His message is straightforward: Roma dancing culture and music are part of the Roma identity. They should be preserved and enriched for generations to come.

4. Conclusion

Concluding my paper, I would compare the topic of Roma early professions with a great unexplored cavern. It offers an abundance of space for exploration and exciting information. Such a research journey seemed easier thanks to the oral history methods helping to reach the origins of information, my interviewees who shaped the topic. The Roma history mostly passed through generations orally; it is worth studying not only to immortalize more than a thousand-year life experience but also to counter-act and take off many stereotypes and prejudices that the Roma people have encountered and are still enduring nowadays. In this regard, “traditional” Roma professions or lifestyles should not be taken as a sole exclusivity or unorthodox living style practiced only by Roma. As I demonstrated, Roma people can thrive in any skill and profession given the environment and opportunities. Early Roma used to be scholars and high-rank warriors before leaving the northwestern part of India. Throughout the course of 1000 years, Roma adapted to various circumstances and survived even the darkest days. They practiced several high-in-demand professions and greatly contributed to the arts, culture and music of the places they resided.

The topic of Roma’s early professions needs more study. I encourage further research on specific ventures: the Roma elders have invaluable information and just exciting stories, which the younger generation must listen to and preserve! Finally, I just reiterate that people are never prone to the only occupation or lifestyle as some ill-advised politicians or scholars suggest.

Literature:

Roma History Factsheets (n.d.). Council of Europe. Retrieved from https://www.coe.int/en/web/roma-and-travellers/roma-history-factsheets

Taylor, A. (2022). Albanian Blood Feuds: More Than 10,000 Revenge Killings in 30 Years. Tirane, Albania.