Greece during the 1950s was a country devastated by the German-Italian occupation during World War II and by the fratricidal civil war that followed. In spite of the improvement in living standards, poverty and unemployment—especially in the rural areas—were at high levels. On the other hand, another country a few thousand kilometers north of Greece was making gigantic steps towards economic growth. Germany, which soon was to be divided by the Berlin Wall, having been completely destroyed during World War II, was growing rapidly and was in desperate need of laboring hands.

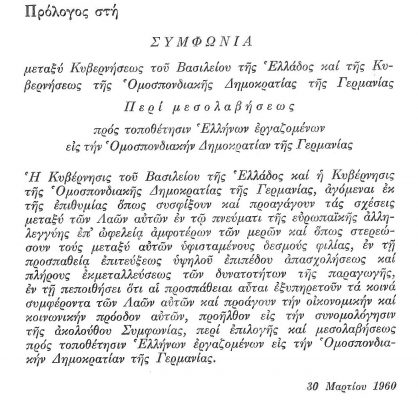

In March 1960, an official bilateral treaty was signed between Greece and the Federal Republic of Germany, commonly known as West Germany. This agreement stated that the Greek state would act as a mediator for recruiting Greek workers in the Federal Republic of Germany. Between the years 1960 and 1973, approximately half a million people, mainly from northern Greece, migrated to West Germany seeking an improved standard of living. Greek workers, as well as workers from Spain, Italy, and most famously, Turkey, called “Gastarbeiter,” played a vital role in the post-war “economic miracle” of West Germany.

Prior to this major movement, Greeks had looked for a better future overseas, e.g. in America and Australia. In this period, we see that the Greek state tried to make them turn their gaze within the European continent, in order for them to return more easily and not be “lost” to Greece forever.

The Question

Even though Greek “guest workers” in the Federal Republic of Germany played an important role on the post-war German economic boom, they were never actually considered to be part of the German society during the 1960s. The responsibility for this phenomenon lied at first with German state policy, and then with the Greeks’ way of living that had them live in their own micro-society within the German one. Consequently, most of them returned to Greece, since they did not integrate into Germany, while the small number who stayed were partially integrated over the years.

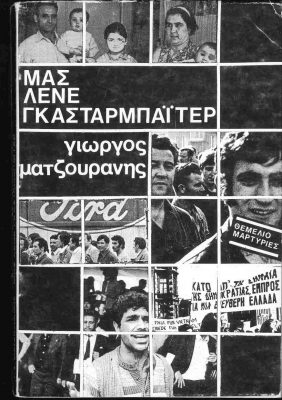

To investigate this question, I interviewed ten people who had all migrated to West Germany during the 1960s—except for one who was born there during that time. The vast majority of them lived in West Germany for only a few years, except for Vassiliki Manisoglou, who lived there for 57 years. This interview was quite helpful in identifying the differences in Gastarbeiters’ lives before and after 1973.[1] Except for the interviews I have conducted, a major source for my research was the book Μας λένε Γκασταρμπάιτερ (We are called Gastarbeiter) by Giorgos Matzouranis. This book, published in 1977, contains testimonies of Greek Gastarbeiters in West Germany and provides a useful counterpoint to my interviews since the interviews were conducted in the 1970s.

In Greece

Living conditions in Greece, as mentioned above, especially in the rural areas, were gruesome. Unemployment was at high levels, in Northern Greece in particular. The news that Germany “opened” as they said, gave people hope and made them imagine a better tomorrow for themselves and their families. As all the interviewees stressed, poverty was quite intense, and the standards of living were very low. Vassiliki Manisoglou, who moved from Kavala to Esslingen, says, “I used to work in the tobacco fields. It was a difficult and demanding job, but tobacco’s price was low, so we were not well-paid.” Olympia Karatza, who also moved from Drama to Esslingen, agrees that, “Poverty left us with no choice but emigration,” and her husband, Stefanos, adds, “Since our governments here in Greece did not take care of us, we had to leave.”

The procedure

The bilateral agreement indicated that the guest workers were to be selected by the German corporations prior to their movement. Thousands of people lined up outside the various German Committee’s offices all over Greece, in order to file an application. In most of the cases the only prerequisite for a man or a woman to be selected was his or her optimal health. During the first few years, almost exclusively men went to Germany, and then either they returned to Greece to get married and leave again with their spouses, or if they were already married, they sent an invitation to their wives to join them. In all, 90 percent of the whole moving population belonged in the 18-35 age group.[2] Since they were destined to be unskilled workers, their health was their only qualification. Many people were examined by a doctor for the very first time. Theodora Tatsiou states, “The medical examination was quite thorough. Most of them had never been examined by a dentist before, and they were not familiar with dental hygiene, but if their teeth were not perfect, they were not cleared to go. It is rumored that most of them repaired their teeth at the time.” Temporary medical examination centers were created in Athens, Thessaloniki and other major cities for the thorough examination of the future Gastarbeiters. As Olympia Karatza says, “We went to Athens for a week to be checked by doctors. They took samples of our blood and urine.” A Greek Gastrbeiter situated in Esslingen in 1969 stated, “I felt like an animal. The doctor examined my teeth, listened to my heart, x-rayed my chest, squeezed my muscles and gave me the capability note.”[3]

Following the first wave of movement, the Gastarbeiters that were already in West Germany had the opportunity, in agreement with their employees, to send an invitation home for their relatives and friends. This invitation was specific about their destination town and the factory that was offering them a contract. Contracts were sent and signed in advance. Irini Christou says that every contract, signed before the trip, was really specific about the place and the job you were sent to do. Vassiliki Manisoglou and her sister Kyriaki were both invited by their older brother, who was already in Germany, through the factory he was working: “Everything was arranged. The trip, the accommodation and the job. All was predetermined before we left.” Stefanos Karatzas was invited by a fellow villager of his in 1964, who had already been there for a few years. Four years later, his wife, who had stayed in Drama with her two children, followed him.

The German state never identified itself as an immigration-state, unlike the USA earlier. Gastarbeiters were not granted permanent residency in West Germany, and as soon as their contract—usually of a two-year duration—was over, they had to return to Greece—unless the contract was renewed by the factory or they found another legal job. As historian Ulf Brunnbauer put it, “the temporary nature of the intended migration was the essence of the recruitment treaty.”[4] Both German and Greek governments used migrants conveniently. Germany considered them as productive labor that could be easily disposed of, and Greece used them to address its major unemployment issues and also saw them as a source of money sent back to Greece.

The Journey

The journey was organized and funded by the German Committee with the assistance of the Greek Ministry of Labor. The vast majority were transported by the ship Kolokotronis[5] to the Italian harbor of Brindizi and then by train to Munich, where the screening took place. A vivid narration follows:

The other method of transportation was the train from Athens and Thessaloniki through Yugoslavia and Austria. Evdokia Karageorgiadou describes this experience: “I went by train. It was really heartbreaking. In the train, there were cassette players that played songs of Stelios Kazantidis[6]. They were really meaningful for us, because the lyrics were about emigration. People got emotional and wept.”

The heims

When they arrived in Germany, Gastarbeiters were never left alone to act freely. They had to follow what their peers did before them; follow the supervisor’s orders. The newcomers were awaited in the Munich train station—that would become famous in Greek popular music[7]—by the firms’ representatives and were then transported to the various cities of destination.

Vassiliki Pavlaki says, “Representatives and interpreters waited for us and gave us chocolates and bananas. Then, they placed us into buses for our final destination. When we arrived, the men were taken to the office for the paperwork, and we were driven to the firm’s heim.” The major firms owned large buildings that were offered for the workers’ housing. These facilities were called in German heims. In most of the cases, heims consisted of large dormitories with common bathrooms and kitchens. A variety of heims were available in terms of size, conditions and facilities. Vassiliki Manisoglou and Evdokia Karageorgiadou both stayed in heims that had four-person dormitories, only for women. Men were forbidden in the women’s dormitories. Only married couples were allowed to live together. Marika Kyrgialani lived in a heim in which every family had its own room but had a common kitchen. Heims were usually situated in small villages on the outskirts of major towns, near the factories. The living conditions in the heim were not always pleasant.

When they left the heims, Gastarbeiters were expected to find their own place, which was a rather difficult procedure since the rents were quite high compared to their salaries. In many cases, they had to live with other relatives in order to divide the expenses.

In the Workplace

Workers were transported by buses to the factories and worked there as unskilled workers, sometimes in jobs that were harmful for their health. Olympia Karatza explains, “I had to work an electric welding machine, and all the sparks were falling on my hands and apron. My hands still have marks.” Evdokia Karageorgiadou said that her husband worked all day by the ovens and had to inhale all its emissions. Giannis Pavlakis had to spray the car seats with a toxic liquid rubber. They were paid in a system called akkord, which means that they were expected to produce a certain amount of products for a certain period of time—hour, day, week or month. If they exceeded this specific amount of products, they were paid by piece rate, in addition to their regular salary. Giannis Pavlakis says, “I had to produce 900 pieces per month. During my last month in this firm, I produced 2500 pieces! I was like a machine.” As an unfortunate consequence for the Gastarbeiters of regularly exceeding the expected amount, the akkord, as well as their bosses’ expectations, were raised. A German worker states that there was a small part of German workers that resented Greek Gastarbeiters, because they were so prompt and effective that they ended up making the Germans work more for the same salaries.[8]

Many Gastarbeiters tried to work as many shifts as they could, in order to earn more money and to send remittances back home for their children. Their savings in Germany helped them buy property or start small businesses in Greece after their return. Evdokia Karageorgiadou says, “The wage was three times higher than the one in Greece. Every month we spent only one of our wages and sent the other one back home for the children. From the money we saved up, we bought this property.” Olympia Karatza did the same: “We worked Saturdays, Sundays and overtime to make plenty of money to send back home. We saved and bought a house in our hometown Drama.” Marika Kyrgialani agrees: “All members of our family managed to build their own house.” All the interviewees agreed that their wages were exactly the same as those of the German workers. They agreed that they were treated politely by the Germans, since they were hard working and focused. Theodora Tatsiou says, “Hardworking Gastarbeiters were rewarded. On the other hand, Germans did not appreciate laziness at all.” “Everybody in the neighborhood treated us nicely. You were expected to be consistent,” states Evdokia Karageorgiadou. They were also astonished by the perfectly organized factories, especially in comparison to their experience in Greece: “We [Greeks] will never be so well organized. We are a hundred years behind. Everything was in order. Transportation was on time,” said Irini Christou.

During the working hours, Greeks almost exclusively mingled with other Greek workers. Only the supervisor, called vorarbeiter, spoke German to them or tried to communicate with signals, in the absence of the translator. As a result, they did not have to practice the German language in the workplace.

The Language

Because nobody spoke the language, at first, they were obliged to use translators who acted as mediators, too. In few cases, workers were deceived by translators. Vassiliki Manisoglou remembers that the language was the major difficulty she faced when she migrated: “The first few years were really challenging, because I could not speak a word of German. We moved our hands and legs to communicate. Many years passed for us to learn how to speak German. We could not attend any school.” One might wonder, if the German state wanted Gastarbeiters to be integrated into the German society, why did it not offer some German language classes to them. Even after a period of two or three years, most Greek Gastarbeiters were not able to speak German, because they spent their time only with Greeks. They had only learned the necessary German words for their everyday shopping. Evdokia Karageorgiadou remembers that she always had her dictionary in her bag. Olympia Karatza says that they had learned the necessary words in order to communicate in the workplace and in the grocery stores.

Leisure time

During their leisure time, workers socialized exclusively with other Greeks, usually other family members who lived in their proximity. They used to take walks and picnics in the large parks that seemed exotic to them since parks in Greece were—and still are—quite limited. They used public transportation or walked there. They listened to Greek music and attended concerts of the Greek singers when they were visiting Germany. Giannis Pavlakis remembers that all the major Greek singers, like Kazantzidis and Moscholiou, visited the nearby major town. Not attending these concerts was out of the question.

As many of the Greeks at that time were quite religious, going to church was an indispensable part of their lives in Germany. Even if they had no Orthodox churches nearby, they created makeshift churches in great halls or cultural centers in order to celebrate their great Orthodox holidays, such as Easter and Christmas. They also performed ceremonies, such as marriages and christenings. Irini Christou remembers: “In a wedding, we had to give away the bride because she had no one!”

Keeping in touch

They kept in touch with their families back home by mail or telephone. “We had to go to the post office to call our hometowns in Greece, because not every house had a telephone. So we preferred communicating with letters. If there was an emergency, we were sent a telegram,” says Vassiliki Manisoglou. They visited Greece almost every summer though, and felt like “kings” due to the currency difference; the German mark was at all times much stronger than the Greek drachma. Vassiliki Pavlaki remembers that she and her husband visited Greece every summer for holidays and that they brought gifts for their children who lived there. A significant number of Gastarbeiters, though, did not visit Greece as long as the military junta lasted (1967-1974), because they were afraid that they would be arrested due to their or their families’ political activity. “During the dictatorship, everyone who had a communist background was stalked by moles,” says Evdokia Karageorgiadou. Stefanos Karatzas said, “My brothers were arrested here in Greece, so it was really risky for me to visit. When I came in 1974, following the fall of the dictatorship, it was seven years since my last visit. I had been too afraid to visit.” When Giannis Pavlakis came to visit his cousins in Volos during the dictatorship, he was nearly arrested because his cousins were communists.

The Greek Radio Shows

Two radio stations had one short Greek radio show each: Deutsche Welle broadcasting from Cologne and the Bavarian Radio broadcasting from Munich. These two radio shows were quite popular among the Greek Gastarbeiters, especially during the military dictatorship (1967-1974). These shows were the major connection with the homeland, and during the Junta, the only uncensored source of information they could get about the current affairs in Greece. The Munich Station’s show, or the Pavlos Bakoyannis’ show[9] as it was commonly known, was very famous and influential. Apart from the everyday news, useful information for the Gastarbeiters’ everyday life and work was transmitted.[10] As Eleni Torosi, who worked in the Bavarian Radio for more than 40 years, stated, “The Gastarbeiters absolutely adored Bakoyannis. The show ended at nine. Every night, outside of the studio, there was a group of Greeks. They were kissing our hands and they congratulated us.”[11]

The Children

The Gastarbeiters’ children were either left in Greece, or if born in Germany, they were sent back home to be raised by their grandparents. Either way, they were brought up for years without their parents. As a consequence, parents’ cohabitation with their children following their return to Greece became difficult, since they felt like strangers. Vassiliki Pavlaki, who had already left her older daughters in Greece, says that when she came back for good, her son, who was born in Germany but returned to Greece to be raised by his grandparents, was disobedient and did not listen to her. Evdokia Karageorgiadou was afraid to give birth in Germany, so she came back to Greece to give birth: “I had to leave my baby daughter with my mother and go back to Germany. I hated that I was obliged to do that, but there was no other way.” The children who were raised in Germany had to attend the German schools. If they wanted to learn the Greek language, they had to attend a Greek school, too, usually in the afternoon. Vassiliki Manisoglou says: “My children went both to German and to Greek school. They had to attend the German school in the morning, and then in the afternoon, the Greek one. But they maintained their Greek identity, which was the desired outcome.”

Moving back

The main reason most of them returned was to raise their children. Either they wanted their children to grow up in Greece, or the grandparents were no longer capable of raising them. Evdokia Karageorgiadou said that she had to come back to Greece because she received a letter from her mother telling her that she was sick and that she could look after her daughter. So, she was forced to return. Theodora Tatsiou, who was born and raised for six years in Germany, says, “We had to move back to Greece due to my education. There was no Greek school in a reasonable distance form our house, so my father made the decision for us to move back to Greece. He did not want me in any way to go to the German school.” The maintenance of the Greek identity was a condition sine qua non for the Greeks.

In a number of cases, people who returned to Greece for a short period were not permitted to migrate again to Germany, due to the military dictatorship that was instated in 1967. Evdokia Karageorgiadou stated that she and her husband wanted to go back, but they were not allowed by the Junta regime. If someone was considered to be a communist, he or she could not be cleared to travel abroad, and in most of the cases he or she was sent to exile. The Oil Crisis of 1973 forced European countries, Germany among them, to adopt restrictive immigration policies. As a consequence, return migration increased.[12]

Integration?

Integration, to some level, was achieved over the years, especially for those who stayed in Germany for over a decade. Gastarbeiters became able to communicate more easily, since language was no longer an obstacle for them. Their children were going to school and playing not only with Greeks but also with Germans. Vassiliki Manisoglou says, “My children feel more like Greeks than Germans, because we raised them this way. We always talked to them about our homeland. We had a well-organized Greek Community that preserved all our customs. We celebrated Greek Orthodox and national holidays. We felt more like Greeks than the ones who live in Greece. Maybe because we were immigrants.”

However, it was only a small number that stayed in Germany, while most of the first generation of Gastarbeiters returned to Greece, since they were not integrated at all in the German society. Even though they spent some of their most productive years in Germany, they always felt like strangers who were temporarily living and working there. None of the interviewees had any regrets—actually they are still really grateful—for their decision to migrate, since they earned money that they had no way of making in Greece. They had the opportunity to send money back for their families and to save significant amounts that later helped them buy land, build their own houses and start their own businesses back home. When I asked Vassiliki Pavlaki if migrating was worth it, she nodded towards her house—we were sitting in the beautiful backyard—and said, “How did you think we made all that?”

[1] The 1973 Oil Crisis diminished the need for guest workers and made West Germany close the “working frontiers.”

[2] Ματζουράνης Γ., Μας λένε Γκασταρμπάιτερ, Θεμέλιο, Athens, 1977, p.9. My translation.

[3] ibid.,p.21-22.

[4]Brunnbauer Ulf, Greek Gastarbeiter, Introduction: Greek migration to Germany after 1945 in

https://greekgermanpasts.eu/greek-gastarbeiter/#fn-107-5 (last accessed on 9/17/2020).

[5] Kolokotronis, named after a Greek Revolution hero, was the only ship that made the trip from Greece to Italy at the time. Rumor has it, among the Gastarbeiters, that its condition was horrible.

[6] Stelios Kazantidis is a legendary Greek singer, who sang songs describing the painful experience of emigration.

[7] There are many famous Greek songs that talk about this train station, describing this whole process.

[8] Ματζουράνης Γ., Μας λένε Γκασταρμπάιτερ, p.51. My translation.

[9] Pavlos Bakoyannis supervised the show, wrote most of the scripts and conducted interviews of Greeks around Europe.

[10] Pantelouris, P., Deutsche Welle, Σταθμός Μονάχου in Επτά Ημέρες, Καθημερινή, 12-13-1998, p.10-12. My translation.

[11] Ελένη Τορόση in https://youtu.be/S-61e0A8cqo (last accessed on 9/17/2020)

[12] Kassimi Ch. & Kassimis Ch., Greece: A History of Migration in https://www.migrationpolicy.org/article/greece-history-migration (last accessed on 9/17/2020)

Καλησπέρα σας, βρίσκομαι σε συνεργασία με ένα project του Παντείου Πανειστημίου και αναζητώ κάποιες λεπτομέριες για τις φωτογραφίες που συνοδεύουν το κείμενο. Θα με βοηθούσε αρκετά να έρθουμε σε επικοινωνία.

Με εκτίμηση,

Αλέξανδρος Μηνάς