Introduction

At the beginning of the 20th century, the Greek community of Egypt was economically and culturally thriving and generally played an important role in the social life of the country. Its activities facilitated the interaction of Greek and Egyptian culture to the mutual assimilation of individual characteristics, to the extent that this was possible – especially if we take into account the different religious background, the linguistic barrier and the distinct national origins.

The term “Egyptiotes”, which refers to the Greek inhabitants of Egypt highlights the connection of the two countries and the hybrid identity of these people1. Most of them lived in Alexandria, which personified the cosmopolitan spirit of the time. 2 The Italian, Greek and Jewish inhabitants of Alexandria played a big role in the prosperity of the seaside town.

The advancement of Hellenism in Alexandria took place simultaneously with the emergence of the city as a large commercial and transit center of the Mediterranean, but also its development into a hub city with a European side, thanks to the European, and particularly Greek element that operated there. Alongside Greek traders, industrialists and businessmen, a large number of Greek residents of the country worked as employees in foreign businesses, banks, etc., thus creating one of the most populous groups of foreign nationals in Egypt.

The Greek Community of Egypt, founded in 1843 by Michael Tositsas, supported, among other things financially, the development of the Greek element. With its assistance, Greek schools, hospitals, orphanages, cemeteries, theatres, restaurants and recreation centers and even dance schools were founded. The Greek community had even developed its own dialect, which was an amalgam of the Greek, Arabic, French, English and Italian languages.

The decline of Alexandrian Hellenism, that once numbered 120,000 people, began in the 1950s, partly as a result of Nasser’s policy. However, the large Greek community that had lived in Egypt for many years left partly due to their desire to go back to their native country as well as the political developments and how these affected their life. Sadly, because they had neither Egyptian nor Greek nationality – having left Greece decades earlier, their lack of citizenship effectively rendered them stateless, turning their hope of returning to Egypt into a chimera.

While the written sources on the subject are not few, most of them lack the personal touch oral history provides. How can one discuss a story of migration and loss without speaking to those who experienced it first hand? Despite growing up in a family whose roots derive from this community, I realized I knew very little about my grandfather’s life in Egypt and the story of how and why his family decided to cross the Mediterranean and come live in Athens.

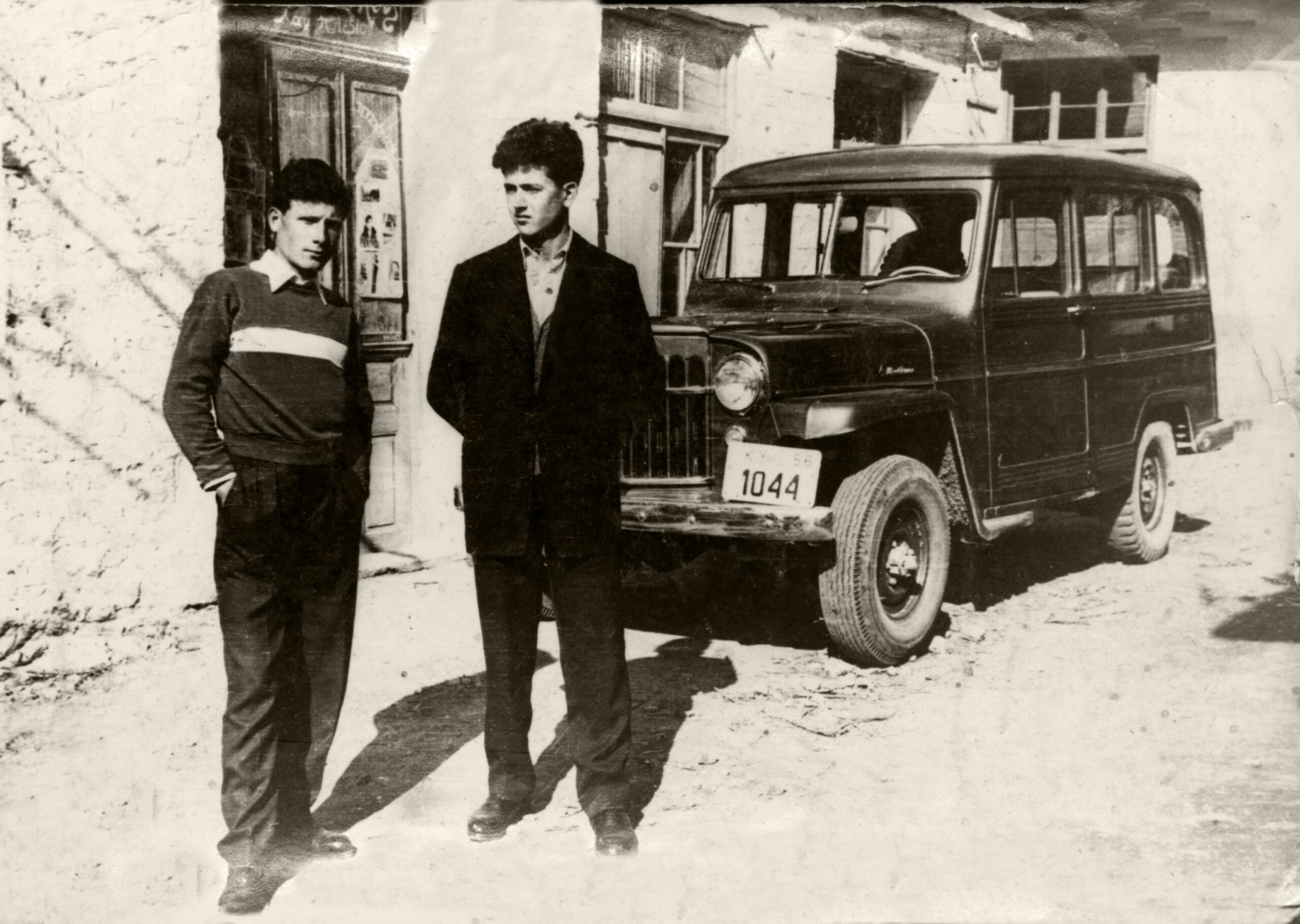

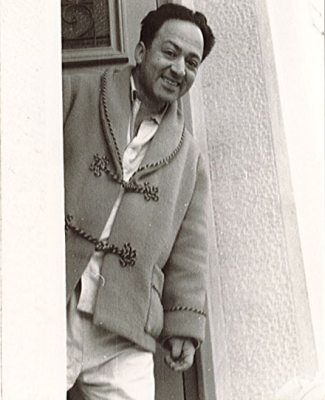

My grandfather, Vassilis Alexandrakis was born in October of 1926 in Alexandria of Egypt and was raised in a rather wealthy family of Egyptiote Greeks originating from the region of Rethymno in Crete. He lost his father at a young age and was adopted as an infant by his mother Angeliki, whose fortune ensured a pleasant living and proper education for the period. He attended Alexandria’s Averofio Gymnasium and, after finishing his studies, he joined the Greek military forces that were stationed in the Middle East following the country’s occupation by the Axis. He returned to Alexandria when the Second World War ended and the Greek army-in-exile was disbanded, where he learnt of his mother’s death and the wasting of her family’s possessions. As a result, he learned the craft of cooling and struggled to make a living while looking for ways to better the quality of his life.

The Interviews

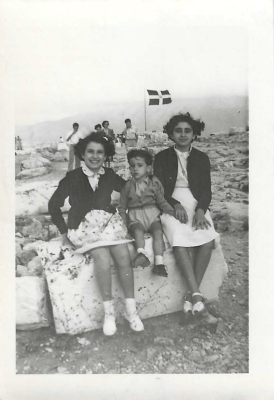

In 1954, the majority of his family also relocated to Greece, where they have remained to this day. One of them is Vassileia Alexandraki, his niece. Now at 77 years old, Vassileia told me about her upbringing in Alexandria, her relocation, and the life she and her family have created in Athens. Konstantinos Pavoudis, who was born in 1958 and moved away from Alexandria in 1962, has few memories of his hometown. He, on the other hand, was on his own mission to solve the riddle of his life and discover where he belonged. As a result, his study and knowledge on the subject were critical.

In addition, I have in my possession two of Vassilis’ diaries, one from 1948 and one from 1952, describing both his life in Egypt and his journey back to Greece that I have used to author this paper.

The Greek experience in Alexandria

The Greeks of Egypt’s societal rank and economic might were mirrored in their residences. They usually lived in large appartements with 3 or 4 bedrooms, dining halls and lounges with chandeliers, Persian carpets, ornamental crystals, and pianos. Vassileia Alexandraki recalls her childhood in Alexandria as being extremely restrictive and repressive, it was “suffocating for a small child”. Contrary to other kids her age, she was not allowed to play outside, which made her daily life monotonous in conjunction with her exhausting school schedule. She started learning Greek, English, French, and Arabic in the first grade, with the majority of students also studying Italian due to the large Italian population in the city. Konstantinos, who was also born in Alexandria, had a more carefree life. His father, who co-owned a barbershop with an Egyptian, was more amenable to Alexandrian culture. That isn’t to suggest he didn’t respect Greek traditions and customs. He was simply more immersed into Alexandrian life than the average Greek. “I remember often playing in Al Shalalat, a big park with trees, ponds and such”, he said, reminiscing about how he enjoyed the untroubled life that was granted to him. His family spent their weekends in Abu Qir, a coastal town just over 20 kilometers from Alexandria. It’s worth noting that an Egyptiote ‘s experience varied greatly based on one’s social class. While poorer families did not have the same level of comfort as wealthier families, they undoubtedly experienced more of Egypt and all it had to offer.

It’s fair to assume that, like the other European powers in Egypt at the time, most Greeks lived an opulent lifestyle that allowed them to live comfortably. They did, however, live at the expense of the indigenous people. Egyptians were unquestionably oppressed. As Konstantinos pointed out: “They were slaves in their own country, servants.”. When speaking with an Egyptiote, it is possible to notice that, while proud of their societal rank in Alexandria, they are ashamed of how their families treated Egyptians. It’s no secret that Greece and Egypt’s connection goes way back. Documentaries and books talk of the shared love and history between Greeks and Egyptians. However, Vassileia says that her connection with the country was strained at best. When Umm Kulthum’s 3songs played on the street, the now 77-year-old woman recalls her father closing the house’s windows. “He would get pissed with these songs, the Arabic ones”, she recalls. The fact that anything non-European was considered “filthy” explains his opinion on one of Egypt’s most renowned artists. This sense of superiority pervades the entire Greek society of Egypt, owing to the fact that Egyptians were made to execute duties that the other ethnicities refused to do. An Egyptian was assigned to any unpleasant task, such as walking the dog, doing the dishes, or doing the laundry. Konstantinos did not share this experience. His family’s lower social standing allowed him to be more open to local customs and practices. His father had few societal duties and expectations to meet. In contrast to Vassileia’s family, he was permitted to occasionally eat falafel and listen to Arabic music.

After the war, the Alexandrakis family collaborated on a cooling company run by Vassileia’s father. In a diary entry from 1948, Vassilis characterizes his days as “monotonous and dull”. His daily routine included going from home to class, then to work, the Greek Union, and finally back home.

The majority of the men spent their days socializing at the Greek Union’s restaurant or at the cinema. The women usually spent their days visiting friends and promenading around town. Greek Egyptiotes mostly kept to themselves. They did tend to interact with Italians and other Europeans, but they preferred to stay to themselves. They were intent on securing the Greek community’s existence in this large global metropolis.

Greek festivities, such as Easter and national holidays, were extensively celebrated. Every Easter, the Epitaph procession would pass along the streets of Alexandria, attracting huge crowds. According to Konstantinos, people would even rent spots on the sidewalks to place their chairs so they could enjoy the ceremony more comfortably. Large parades and musical events were held to commemorate Greece’s independence. Greece was more than a country to the Egyptiotes.

The beginning of the journey to Greece

The Greek community’s prosperous lifestyle came to a sudden stop in July of 1952, when Gamal Abdel Nasser and Mohamed Naguib, along with 88 other military officers, removed King Farouk I from power and adopted a policy of liberating Egypt from the grip of the foreign powers that had oppressed it for centuries. While this movement is considered a Revolution by most, there are those who consider it a coup d’ état. Those who consider it a revolution also emphasize how justified it was, given the Egyptian people’s position in their own country. The abolishment of the capitulations a few years earlier 4 and the economic reforms 5 that followed resulted in the loss of power and status for a number of Greek, Italian, French, and English businessmen.

A few months before these events, and while the political scene in Egypt was tense in January of 1952, Vassilis embarked on a journey to Australia with the goal of relocating to the nation where other members of his family had already settled. However, he decided to board a ship and return home less than 6 months later, just after earning enough money to pay a ticket home. His plans to return to Alexandria were thwarted by the fact that Egypt’s political situation had radically changed. He and the other Greek passengers on board were denied entry to the nation and were sent to Marseille. Despite their best efforts, they were unable to return to Egypt and were therefore transferred to Piraeus.

Vassileia’s family left Alexandria in 1952, at a time when Naguib was in charge of the country and tensions were high. While Naguib was a philhellene, the reforms were shaking the foundations of the community. Her father never told the rest of the family that their move to Greece was permanent. “One day we were just normally going on with our lives and the next we were aboard a ship back to Greece” Vassileia explains. As a result, they packed only a small bag, locked up their house, and went to the port, leaving behind all of their prized possessions such as heirlooms, jewelry, clothes, as well as their entire house! After all, they were not allowed to take anything with them! Inside the boat called “Achilleas”, the soldiers guarding the port and inspecting the passengers made a big deal about not letting anything valuable leave the country. As a result, they attempted to forcefully remove the gold bracelet 9 years old Vassileia was wearing, which was a gift from her baptism. And this was not the only example of force used by the Egyptian military at the time!

Vassileia is unsure of the reasons for her father’s choice to leave Egypt. However, considering the country’s abrupt shift in socioeconomic dynamics, his decision is not surprising. Vassileia vividly recalls the Quran being required to be taught in schools, but there is no evidence to support that this was the case in Greek schools. The education the Egyptiotes received was very much centered around Greece, making it hard for Egyptiotes to truly integrate themselves into the Egyptian society. However, around the same time Vassileia’s family left Egypt, learning Arabic became more demanding as the schools had to follow the government’s guidelines. 6

Following the 1952 Revolution, the relationship between the oppressed Egyptians and the foreign residents of the city changed drastically. The natives, who had finally had enough of being inferior in the own land, started showcasing their hatred and disdain towards Greek, Italian, French and English citizens of the country. The Egyptians had become aware of the power they possessed and were excited to take charge of their lives and send away the foreigners that were taking their land and money. With this, began the journey of the Greek community’s back to what they considered their homeland.

Konstantinos returned to Greece at a much later date. After years of struggling to make ends meet in post-revolution Egypt, his family relocated in 1962. As the 1961 review of the activities of the Alexandrian Greek community stated: “The radical measures for the economic reform of the United Arab Republic had important ramifications to our community” 7. It goes on to illustrate how, despite everything the Greek community had to offer Alexandria, it was excluded, ignored, and pushed to return to Greece. 8 Despite their different arrival dates, Vassileia and Konstantinos agree on one point: settling in Greece was much more difficult than expected.

Life in Greece

Vassilis arrived in Greece on October 7th, 1952, and it goes without saying that Piraeus did not impress him. It’s easy to picture how frustrated he was after a month of traveling from Australia to India, through the Suez Canal to Egypt’s Port Said, then to France, and eventually to Greece, all while being denied permission to return home. He originally settled in Piraeus, where he worked as a coolant. When his cousin, along with his wife, son, and daughter Vassileia, arrived in Greece a few months later, they all relocated to the Athenian district of Zografou, where a number of Egyptiotes had settled.

Vassileia has a bittersweet memory of her first year in Athens. While she was originally very excited to return to Greece (“It was something ideal and extraordinary, the fact that we were going to Greece.”) , the natives were not as enthusiastic. In the beginning, her parents struggled to find work. Her school experience was no different. Her fluency in English and French made her stand out in class, to the point where the other students began to dislike her as a result. Her family also struggled financially. She vividly recalls her first Christmas in Zografou, when her father could not even afford to give her a pencil for homework, in contrast to the room full of gifts she was used to receiving in Alexandria. Vassileia and her cousin Maria decorated a cypress branch because they didn’t have a Christmas tree. The stark contrast between the two encounters has left a mark on her mind and memories.

Konstantinos’ experience wasn’t much different. He recalls his classmates teasing him and questioning why, if he was from Egypt, he wasn’t black. He recounts packing a bag and heading to the train station when he was around 6 years old and living in Perama, a working-class suburb in Pireaus. His mother eventually located him and inquired as to what he was up to. He replied, “I’m waiting for the train to take me home,” recalling the train station near his home, in Alexandria’s Corniche.

Conclusion

Vassileia and Konstantinos have maintained contact with their Egyptiote friends and made it a point to educate their children and now grandchildren about their ancestors. Konstantinos remarked that if he hadn’t met his wife, he would have moved to Egypt and stayed there for the rest of his life. While Vassileia is content with her life in Greece, she describes her relocation to Greece as a “sad, violent and unfair uprooting”, and she makes a gesture with her hand as if she is ripping out her heart as she speaks.

Vassilis met his wife shortly after relocating to Zografou in 1952, where he established his own family, had a full life, and left his last breath in November 1995 at the age of 70. He maintained contact with his Egyptiote acquaintances and family throughout his life in Greece. He participated in all of the Egyptiote Union’s events in Athens, including yearly dances, chess clubs, and excursions, and made sure that his family was well-versed in Egyptian customs.

For a long time, Greek Egyptiotes struggled to fit in. “At times I still wonder where I belong…”, Vassileia says remembering her times growing up in Athens. Even though they felt Greek, they still had ties to Alexandria because of the treasures and memories they left behind, despite the fact that they were no longer accepted there. For a long time, they were on a quest to find their identity. By the time the Alexandrian Greek community was fully assimilated into the Greek society, a long time had passed. Even then, the stigma of having been kicked out of their homes followed them and made adjusting to their new lives even more challenging. They felt as if they didn’t belong anywhere for a long time, as if they didn’t have a home. “Foreigners in Egypt, foreigners here as well,” Vassilis writes in his journal.

Sources

Primary/Archival Sources

Alexandrakis, Vassileios, Unpublished Diaries, 1948, 1952

Secondary Bibliography

Cavafy C. P., “The God Abandons Antony“ , Onassis.org

Chatzifotis I. M., Αλεξάνδρεια – Οι δύο αιώνες του νεότερου Ελληνισμού (19ος-20ος), Elllinika Grammata, Athens 1999

Danielson, Virginia L., “Umm Kulthum.”, Britannica.com

Haag Michael, Αλεξάνδρεια, Η πόλη της μνήμης, Okeanida, Athens 2005

Ntalahanis Aggelos, Ακυβέρνητη Παροικία, Panepistimiakes Ekdoseis Kritis, Heraclion 2016

Sakkas John. “Greece and the Mass Exodus of the Egyptian Greeks, 1956-66”, Journal of the Hellenic Diaspora 35 (2009): 101-117.

- Ntalahanis Aggelos, Ακυβέρνητη Παροικία, Panepistimiakes Ekdoseis Kritis, Heraclion, 2016, p. 25. ↩

- Haag Michael, Αλεξάνδρεια, Η πόλη της μνήμης, Okeanida Publications, Athens, 2005 . ↩

- Egyptian singer, “one of the most famous Arab singers and public personalities of the 20th century.” Danielson, Virginia L., “Umm Kulthum.”, Britannica.com . ↩

- “In 1937, the capitulations, the special status and privileges granted to foreigners that protected them from taxations and from immunity from local courts, were abolished. The trend toward Egyptianization which followed was particularly enhanced by the joint-stock companies law of 1947, which stipulated that 51 percent of the capital, 40 percent of the board of directors, 75 percent of the employees, and 90 percent of the workers be Egyptian” Sakkas John. “Greece and the Mass Exodus of the Egyptian Greeks, 1956-66”, Journal of the Hellenic Diaspora 35 (2009): 105. ↩

- A number of laws were enforced after the Revolution aiming to Egyptianize the country. “In September 1952, the agrarian reform law provided for the limitation of agricultural land holdings to a maximum of two hundred feddans (slightly more than two hundred acres) and expropriation of the rest for redistribution among the fellabin.” Another example is the 1957 laws that mandated that “all commercial banks, insurance companies, and commercial agencies for foreign trade would be fully Egyptianized in management and capital within a period of five years.” Sakkas, “Greece”: 106. ↩

- Ntalahanis, Ακυβέρνητη, p.90. ↩

- Chatzifotis I. M., Αλεξάνδρεια – Οι δύο αιώνες του νεότερου Ελληνισμού (19ος-20ος), Elllinika Grammata, Athens, 1999, p.112. ↩

- Chatzifotis, Αλεξάνδρεια, p.113. ↩