Introduction – Global History and the Backlash to Integration

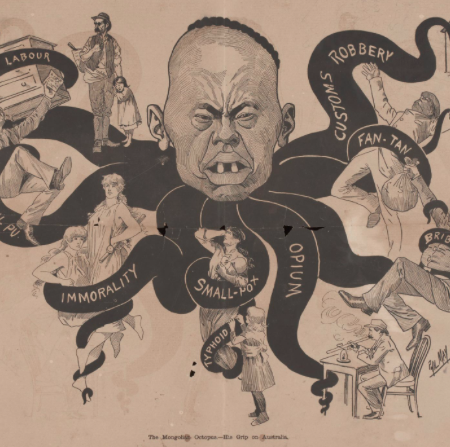

Global history often tells the history of globalization, increasing integration, progressivism, connection and inclusion. However, the narrative of global history as the history of globalization only is selective and shaped as much by what it excludes as by what it includes. Integration, connection and inclusion go along with disintegration, disconnection and exclusion. Those whose monopoly on power, speech and history-writing is challenged, perceive inclusion as exclusion.1 This form of disintegration and what American writer and professor of sociology Arlie Russell Hochschild describes as the feeling of being a “stranger[…] in [one’s] own land,”2 manifests itself in a border-crossing, global backlash to integration. This global backlash expresses itself through phenomena like the election of President Donald Trump in 2016, Brexit and the global rise of authoritarian populism.3

Within the context of the History Dialogues Project, I explored how this backlash to integration manifests itself locally at the micro-level through the actions of the Stanford College Republicans at Stanford University. This essay focuses specifically on the question of how the Stanford College Republicans as a group have changed since the election of President Donald Trump in 2016. It argues that the Stanford College Republicans became a polarizing activist group in 2017 following a change in leadership on both the external and internal level, namely the external change in US leadership on the national meso-level and the internal change in the Stanford College Republicans’ leadership on the micro-level. Mirroring Trump’s positions held and language used on the meso-level, they contributed to crossing borders of the thinkable by moving the Overton-Window towards normalizing Trump-conservative positions on the micro-level.

I chose Stanford University as an example since the university strives to have one of the most integrated and inclusive campuses in the world.4 This is especially insightful as these are the very conditions to the backlash I seek to explore. Rinus Penninx defines inclusion and integration as “the process of becoming an accepted part of society” and refers to this acceptance on a “legal-political, the socio-economic, and the cultural-religious”5 level. Building on this idea, I understand both concepts as the acceptance of groups of people previously excluded from spheres of power on all three levels, who now gain access to these spheres. This contributes to a backlash against integration.6 According to the Cambridge Dictionary, a backlash is a “strong feeling among a group of people in reaction to a change or recent events in society or politics.”7 Shortly after the presidential election of Republican President Donald Trump, a right-wing populist, Stanford College Republicans, “once dedicated to quiet weekly meetings and canvassing for conservative politicians — [became] a fully-fledged activist organization.”8 The Stanford College Republicans have become a well-known and extremely polarizing organization. They dedicated themselves to building what the former Activism Director of the Stanford College Republicans and one of my interviewees, describes as a “counter-culture” to the progressive Stanford college culture. This emergence of the Stanford College Republicans as a popular actor on campus has to be understood in the context of external and internal factors including the Trump election and a change in the Stanford College Republican’s leadership with the presidency of Republican activist John Rice-Cameron.

After a brief overview of the methods, terms and concepts used in this essay, I focus on the internal factor of the change in leadership of the Stanford College Republicans and how it affected the organization’s trajectory, mission and behavior. Moreover, I explore how the Stanford College Republicans began to describe their own positions, what language they started using and which actions they carried out under the presidency of John Rice-Cameron. Further, the essay takes note of the Stanford College Republicans’ perception of intensified progressivism and repression of conservative voices on campus and support of conservatism from the wider culture. I demonstrate how the external factor of the Trump election on the meso-level connects to these findings on the micro-level. I am aware that other factors also played a role in how the organization changed. However, I chose to focus on the factors the Stanford College Republicans themselves found to be decisive. I refer to interviews I conducted with the former Activism Director, the former Executive Director of the Stanford College Republicans, and a student journalist from the Fountain Hopper. All were active during the time the change occurred under the presidency of John Rice-Cameron. While the significance of three interviews might be limited, I also strongly built upon the student newspapers Stanford Review and Stanford Politics, especially its portrait of John Rice-Cameron, “John Rice-Cameron Wants To Make Stanford Great Again,” its extensive coverage of the organization and the organization’s Facebook posts as primary sources. Moreover, I refer to secondary sources including The Public Religion Research Institute’s study “Beyond Economics: Fears of Cultural Displacement Pushed the White Working Class to Trump,” when highlighting how the Stanford College Republicans mirror meso-level efforts to push back against efforts of integration. When demonstrating how the Stanford College Republicans push back against what they perceive to be an extremely liberally biased campus culture, I build upon Annemarie Vaccaro’s article “What Lies Beneath Seemingly Positive Campus Climate Results: Institutional Sexism, Racism, and Male Hostility Toward Equity Initiatives and Liberal Bias,” which she published in Equity & Excellence in Education. The essay concludes with a reflection upon the lessons learned throughout the research process highlighting the importance of empathy.

Concepts and Methods

I conducted three 60 minute interviews with the aforementioned interviewees. I approached the two Stanford College Republicans because as the Executive Director and Activism Director they contributed and could speak to the change of the organization. Further, I approached a student journalist from the Fountain Hopper since she not only covered the change of the organization but as a Stanford student herself, she also contributed an informed outsider’s perspective. In order to understand Stanford College Republicans as an organization in the context of Stanford college culture, my interview questions were the same for all interviewees and the three questions I focused on were: (1) Could you describe Stanford College culture to me? (2) Could you describe the Stanford College Republicans’ culture and how it fits into the former? (3) Did you notice a change in Stanford college culture and/or the Stanford College Republicans’ culture? I contextualized these interviews and further off-the record conversations with Stanford students with the organization’s self-representation online and articles from Stanford Politics, a left-center student newspaper, and The Stanford Review, a right-center student newspaper. I chose both student papers since they covered the organization from a Stanford student’s perspective.

Within the context of this project, I used the framework of macro-meso-micro levels of analysis and highlight their connectedness and how they influence each other. In “Micro, Meso and Macro Levels of Social Analysis,” published in the International Journal of Social Science Studies, Sandro Serpa and Carlo Miguel Ferreira refer to the premise of this framework: “in every sociological theory, we can recogni[z]e a minimum unit (micro) and a maximum unit (macro). Between the extremes, several other intermediate levels (meso) can also be conceived.”9

I focus on the meso-and micro-level. For the purpose of this project, meso-level refers to the national context of the US, and micro-level to the local context of Stanford University. While the backlash to integration manifests itself on all three levels, I concentrate on how the meso-level backlash manifests itself on the micro-level. I highlight that it manifests itself in how the Stanford College Republicans have changed as an organization mirroring meso-level developments towards the normalization of Trump-conservative thought. Within the context of internal and external factors, the organization changed in how it conceptualized its role on campus and started focusing on culture instead of policy, moving the Overton Window towards normalizing Trump-conservative positions at Stanford University. The theory of the Overton Window is based on the idea that there is a window of ideas and views that are acceptable in public discourse. Ideas inside the window are normal, ideas outside the window are unthinkable. The window can move by forcing people to consider views at the extreme outside of the window. The consideration of unthinkable ideas makes all less extreme views seem thinkable by comparison, slowly moving the window in that direction.10 By doing so, the Stanford College Republicans crossed the borders of the thinkable.

Stanford College Republicans – From a “Wine and Cheese club” to a “Fully-Fledged Activist Organization”

Located in the blue state of California, Stanford University is often seen as a hub for progressive, left-leaning liberal views. In the context of this project, I define the polysemous term “liberal” as a politically progressive and left-leaning view. According to the Cambridge Dictionary it accepts and allows “many different types of beliefs or behavior”11 while “conservative” is a position “tending or disposed to maintain existing [traditional] views, [values] conditions, or institutions”12 and opposed to change.13 I distinguish between conservative in general and Trump-conservative in particular, which I define as a very extreme and excluding set of beliefs directed against those whom one seeks to exclude, defined by what and whom it opposes rather than by what it supports. There is discord among students with regards to the degree of progressivism and liberalism at Stanford University. While the Stanford College Republicans’ former Activism Director unsurprisingly describes Stanford as extremely progressive and left-leaning, other students, including a student journalist from the investigative student newspaper the Fountain Hopper, describes Stanford as “leftist center” arguing that students are moderate and “not politically engaged.”14 This ties in well with how members who were part of the change that the Stanford College Republicans went through as an organization describe the group before the change in leadership: until 2016, Stanford College Republicans were a largely unknown student organization that sometimes held debates without raising attention – reporters and former members describe it as a “wine and cheese club.”15 Now, they are widely popular as an activist organization. How did this change happen? For this change to occur, one may point to an internal key factor that interacted with the external factor of the Trump election: the change in leadership of the Stanford College Republicans and its effects on the organization’s mission and work.

Until the rise of Stanford College Republicans, the Stanford Conservative Society was the main organization for conservative students. They “did very many little wine and cheese events, a few speakers, and such,”16 confirmed Philip Eykamp, former secretary of the Stanford College Republicans. Under then-president Elise Kostial, the Stanford College Republicans had about 12 members and were unknown to most students.17 Enter John Rice-Cameron, then Financial Officer of the Stanford College Republicans. John Rice-Cameron revitalized and changed the organization after rising to its presidency. He described his goal as follows:

This effort to achieve more balance, ties into how the Stanford College Republicans perceive Stanford college culture more broadly as being unfairly liberally biased and repressive of conservative voices. The former Activism Director and the former Executive Director both explained how the Stanford administration’s funding rules for events make it unfairly harder for a conservative student organization to receive funding. One such rule specifies that half of an event’s funding has to come from Stanford University and its institutions. The former Activism Director and the former Executive Director highlighted how liberal student organizations have the support from almost every department and institution on campus.19 They can turn to the Arts and Humanities Department, the Politics Department or any other department to secure funding for politically liberal events. By contrast, these departments tend to not want to be associated with conservative events making it harder to receive funding for conservative speaking events. One exception is the Hoover Institution, a conservative think tank on campus. The former Activism Director explained that while the Hoover Institution is more supportive of inviting conservative voices with a past in politics, it is unlikely to provide the funds when it comes to particularly controversial Trump-conservative speakers without a background in politics. Another example the former Activism Director referred to, is the Stanford administration’s rule of making filming in dorms illegal. According to him, students systematically took down flyers for speaking events of the Stanford College Republicans inside the dorms. The Stanford College Republicans started filming them when doing so to publicly shame them. Then, Stanford created a rule that prohibited filming in dorms – something the former Activism Director considered to be a response to that.20 These are only two examples that reinforce the Stanford College Republicans’ view that the campus climate is characterized by a strong liberal bias and discrimination against (Trump-)conservatism.

Let us take a brief look at the research on so-called liberal biases and campus culture. Referring to American college campuses in general, sociological studies including Harvard University’s “The Social and Political Views of American Professors” by Neil Gross confirm that college professors and institutions tend to hold more liberal than conservative views.21 However, the homogeneity of political orientations on campus and among the professoriate is not greater than in other professions and work cultures. This suggests that there is a degree of diversity of opinion on campus that reflects the diversity of opinions represented in other workplace cultures and professions.22 While this is what research indicates, what matters is perception and the Stanford College Republicans perceive campus to be extremely liberally biased. In line with that, Annemarie Vaccaro explains that there is a strong resentment and hostility towards that existing and perceived so-called liberal bias and diversity efforts – efforts that constitute moves towards more integration and inclusion – on college campuses.23 This also holds true with regards to the Stanford College Republicans who view the campus and teaching culture to be extremely liberally biased and now strive to create a “more balanced”24 discourse.

The Stanford College Republicans as an organization show an awareness of the fact that its internal culture morphed with the change in leadership in 2017. Not only did my interviewees confirm but also the organization’s website reads:

Before that revitalization, Elise Kostial was the president of the organization. While there was a very short period of time with an interim president between John Rice-Cameron and Elise Kostial, the change between the two illustrates the shift in the organization’s culture and mission. Under Elise Kostial, members refused to comment on Trump after the election in 2016 and they did not endorse candidates in the 2016 election. Kostial “declined to share her personal views”26 and other members “declined to offer comment.”27 With John Rice-Cameron’s presidency this non-polarizing behavior changed radically. Rice-Cameron did not shy away from publicly articulating his views and the Stanford College Republicans’ positions became strongly aligned with Trump’s views. On their Facebook page, the Stanford College Republicans summarized their position as follows:

fThe quote stresses the new direction the organization took under Rice-Cameron’s leadership and highlights the college-internal alignment with positions held by the Trump administration on national meso-level. It shows how the meso- and micro-level are inextricably linked and how the election and Trump support inspired and influenced this new direction. The “[a]ffirmative action is racist”29 part demonstrates this: the Trump Administration’s Department of Justice requested information from colleges regarding their affirmative action and early admission policies flagging potentially discriminatory effects of both.30 The issue is not the request itself but how an anti-discriminatory practice has been reframed to exemplify discrimination against the privileged, in the context of the Stanford College Republicans’ statement, white students. The fact that these newly framed thoughts lead to action on the national meso-level, makes them seem more legitimate on the local micro-level. On their website, the Stanford College Republicans state:

In this quote, the Stanford College Republicans articulate their intent to push back against efforts of integration that imply America has to carry out efforts of integration in the first place. These efforts include affirmative action policies and the acknowledgement of white privilege. “White privilege is a lie”32 also reflects a position held by and backed up by actions of the Trump Administration on the meso-level: President Trump instructed all federal agencies to “identify [and end] all contracts or other agency spending related to any training on […] ‘white privilege.”33 According to a joint study by the Atlantic and the Public Religion Research Institute, affirmative action and the notion of white privilege – both efforts of integration – contributed to a feeling of a loss of identity which in turn contributed to predicting Trump support. Almost half (48%) of white working-class Americans say, “things have changed so much [through efforts of integration] that I often feel like a stranger in my own country.”34 With more inclusion and integration that occurred over the past few years on the meso-level such as the legalization of same-sex marriage in 2015, a sizable number of Americans fear that the cultural landscape is changing so drastically that the country will lose it’s identity – a belief held by a majority (55%) of the public overall.35 Make America Great again. With regards to affirmative action and the notion of white privilege, “more than half (52%) of […] Americans believe discrimination against whites is as big a problem as discrimination against blacks and other minorities.”36 Diana Mutz’ study which she published in National Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences found that being left behind culturally and feeling threatened in one’s group status predicted Trump support: “Those who felt that the hierarchy was being upended—with whites discriminated against more than blacks, Christians discriminated against more than Muslims, and men discriminated against more than women—were most likely to support Trump.”37

The Stanford College Republicans mirror these Trump-conservative views held on the meso-level when saying that affirmative action is racist and arguing that white privilege is a lie. A study by the Democracy Fund Voter Study Group found that what was distinctive about voting behavior in 2016 was the multitude of cultural grievances.38 Developments towards integration and inclusion on the national meso-level were met with a cultural and social fear of loss of identity and the feeling of being excluded from what used to be a status quo that promised stability to previously privileged groups. Recent events in society and politics began challenging that status quo – debates about gender fluidity, wealth redistribution, reparations, the challenge of the concept of traditional marriage – and left traditionally privileged groups feeling like a “stranger in their own country.” A backlash – a “strong feeling among a group of people in reaction to a change or recent events in society or politics”39 – to integration and inclusion occurred on the national meso-level and paved the way for the change in the Stanford College Republicans’ self-portrayal and work on the micro-level as reflected in their statements.

Just as the Stanford College Republicans’ desire to “[b]uild the wall”40 is a clear reflection of Trump’s plan and effort to build a border wall between Mexico and the United States in order to prevent immigrants from entering the United States,41 “[d]eport criminal illegals”42 strongly builds upon Trump’s position on and language of immigration: he not only actively and very prominently sought to detain and deport immigrants from the US, but he also called them “illegals,” employing dehumanizing language now used by the Stanford College Republicans.43 This language of dehumanization44 reflects how the Trump-conservative views held on the meso-level, manifest and normalize themselves locally. The Stanford College Republicans’ statement and position – which was issued after the Trump election – became more thinkable as they reflected topics that characterize the wider culture’s discourse on the meso-level. This links to the theory of the “Overton Window” mentioned earlier. The Trump Administration’s positions and actions and its focus on the perceived discrimination of privileged individuals, force people to consider extreme positions outside the window of acceptable ideas. It slowly moves the window towards making these positions more acceptable in public discourse, including the discourse at Stanford University.

Moreover, the Stanford Republicans’ positions do not only reflect the Trump Administration’s positions but also his distinctive linguistic style. The Stanford College Republicans’ positions are phrased in simple, active, mostly three word noun phrases which also characterize Trump’s language. In a study analyzing Trump’s language, Orly Kayam pointed out a similar shortness, simplicity and readability of Trump’s sentences.45 Not only the positions themselves but also the language used to articulate them are reflective of Trump’s. When John Rice-Cameron speaks of “a more balanced direction,”46 it does not only mean more conservative and less liberally biased. In this case it means more Trump-conservative and reflective of the backlash against efforts of integration – affirmative action, racial sensitivity training, immigration – on the meso-level.

Aside from the articulation of the Stanford College Republican’s positions, what did the change under John Rice-Cameron’s presidency look like? Under John Rice-Cameron, the Stanford College Republicans became more aggressive when it came to recruitment and created more visibility through tabling, flyering and inviting polarizing speakers. The group transformed itself from a “wine and cheese club” to an activist organization. Recruitment was a priority for the Stanford College Republicans and visibility was necessary for the success of this effort. They started by setting up tables on campus with statements that were polarizing on a liberal campus. Such statements included “I am pro-guns, change my mind” to spark conversations with students. Thus, they started to create a dialogue with their peers while making their group and its positions more known. While this effort was directed at sparking a conversation and dialogue, other measures such as speaking events were extremely polarizing and made the Stanford College Republicans known on and off campus – as the former Activism Director puts it, they became the “most hated group on campus.”47

The first polarizing speaker was self-proclaimed “Islamophobe” Robert Spencer whom the United Kingdom banned from entering the country on the grounds that he would incite dangerous levels of public unrest and Islamophobia. In a statement Stanford College Republicans called Robert Spencer “a sorely needed perspective to an important conversation about international security.”48 According to an anonymously quoted Stanford College Republican, his views are not conspiracy theories but “beliefs that many of the staff in the White House hold.”49 This shows the ties between the meso- and micro-level. The fact that positions that reflect the pushback against integration – in this case the integration and inclusion of other religions – are held on the national meso-level, is used as a legitimization for bringing it to the micro-level at Stanford. On the national level, the Overton Window shifted and normalized extreme ideas through the presidency of Donald Trump. Now, these ideas became thinkable on campus and the goal was to shift the Overton Window on the campus of Stanford University.

The Stanford College Republicans’ ties to strongly right-leaning media outlets reinforce this connection between meso- and micro-level. The Stanford College Republicans use these ties to attract attention with regards to campus events and perceived discrimination against them. A former student journalist from the Fountain Hopper highlighted that it is easy for the Stanford College Republicans to make events and controversies public since they are supported by media outlets like Fox News, Breitbart, and The College Fix.50 Representatives of the Stanford College Republicans highlighted that Stanford college culture became ever more progressive and described being actively oppressed by Stanford University and the culture on campus after the election of President Donald Trump. While College Republicans felt more accepted in the wider culture on the meso-level, including the aforementioned media outlets, they felt simultaneously less accepted at Stanford University and expressed the sentiment of a backlash against populist conservatism. In the eyes of the former Activism Director, after the Trump election, Stanford college culture intensified its leaning towards progressivism in response to an increasingly right-wing populist wider culture. One may say that Stanford College Republicans met this intensified progressivism with a right-wing populist backlash against the progressive, inclusive and integrated college culture. Now the support from the wider culture and its media emboldened them and Rice-Cameron spearheaded the efforts to push back against Stanford’s college culture.

Stanford College Republicans’ presence in the media links to it sharing and featuring links to Fox News and Breitbart articles dealing with a broad range of issues including immigration and gender fluidity on their Facebook and Twitter pages. They also started reposting right-wing pundits including Allie Beth Stuckey and Ben Shapiro. A recent Facebook post reads: “During his “eulogy” for John Lewis, Barack Obama reminded us of the fact that he was the most radical, divisive and anti-American President in recent history.”51

This commentary situates the organization in a strongly Trump-conservative corner. By sharing links to highly partial and oftentimes inaccurate articles – data from the Poynter Institute’s Politifact Factchecker reveals that 42% of Breitbart media portrayal is false52 – the group becomes extremely political on both the meso- and micro-level. Social media has tainted the lines between meso- and micro-level since one’s impact on social media goes far beyond campus. The efforts of an organization that exists on the micro-level and is locally rooted on a college campus contribute to simultaneously shaping a local and a national discourse through partial and misleading information. They contribute to what Dustin Carnahan calls “adding fuel to politically contentious fires and escalating social issues to the level of crises.”53 One example is how reposting articles helps these articles gain traction and reinforces an algorithm that prioritizes widely shared over accurate information.54 Every individual’s social media behavior matters with regards to shaping a discourse, but the Stanford College Republicans’ social media behavior is especially relevant since they have over 5000 followers on Facebook alone. In comparison to other student organizations this constitutes a huge following. This success ties in with the former Executive Director describing the organization as the most strategically organized and powerful political group on campus. He attributes this to being a conservative minority on a liberal campus which gave them more drive to succeed compared to liberal student groups.55

Back to their action and mission under John Rice-Cameron’s presidency: While Rice-Cameron’s aim for a “more balanced dialogue”56 featured prominently in his Stanford Politics portrait, it is not how the organization describes itself on its website and how he described the organization’s mission in other contexts. In a leaked email to the Hoover Institution’s academic Niall Ferguson, he described the Stanford College Republicans’ goal as follows: “Slowly, we will continue to crush the Left’s will to resist, as they will crack under pressure.”57 This language of not only opposing a current college culture, striving for more balance and aiming to make one’s ideas heard but to also “crush” whom one considers to be the opposition, reveals a different goal: to dominate the college culture and to establish the Stanford College Republicans’ Trump-conservative ideas as the status quo. This ties in with the language used on the Stanford College Republicans’ website and its use of social media. The organization describes its growth and agenda in two phases:

“In Phase I, we overcame attempts by leftists both in the administration and in the student body to prevent conservatives from being heard,”58 efforts like the Stanford administration’s prohibition of filming in dorms and Stanford students tearing down flyers in the first place. “[I]n Phase II, we will normalize conservative ideas at Stanford so that students no longer view conservatism and SCR as fringe or extreme, but rather they consider conservatism as a mainstream ideology.”59 The Stanford College Republicans state that they have already achieved the aims of “Phase I” and “are now able to enter Phase II, where we are now able to ensure that conservatism goes mainstream at Stanford.”60 These structured efforts and long term agenda shows how well organized the organization is and how their efforts are situated in normalizing (Trump-)conservative thought and in moving the Overton window.

This also goes to show how once again meso- und micro-level are inextricably linked – developments that have “gone mainstream on the meso-level” are supposed to go mainstream on a micro-level and both mutually reinforce one another.

Conclusion – The Inextricable Links between Micro- and Meso-Level and the Importance of Tearing Down Walls of Empathy

The Stanford College Republicans underwent a drastic change under the presidency of John Rice-Cameron: from a “wine and cheese club”62 to a “fully-fledged activist organization.”63 This change has to be seen within the context of a change in leadership on the meso-level with Donald Trump rising to US presidency and moving the Overton Window to normalize Trump-conservative thought and dehumanization. On the micro-level, the change of the organization has to be understood within the context of a change in leadership from Elise Kostial to John Rice-Cameron. With Rice-Cameron’s presidency the focus shifted from small policy-focused discussions to a strong culture focus. The change manifested itself through the explicit and at times dehumanizing language used to articulate non-ambiguous positions that reflected Trump-conservative positions, the use of social media and ties to right-wing media outlets, the employment of new methods of recruitment including tabling, flyering and inviting extremely polarizing speakers, and the new longterm and highly organized mission of normalizing Trump-conservative thoughts on campus. Emboldened by the support of the wider culture and media on the meso-level, the group strives to move the Overton Window in a way that mirrors the developments on the meso-level. The development of the organization serves as an example of how meso- and microlevel are inextricably linked and mutually reinforce each other. On the one hand, the change of the organization is emboldened by and mirrors changes and a backlash to integration on the national level and manifests them locally. On the other hand, it is not constrained to the micro-level but reinforces the national pushback by doing so. Beyond pushbacks, backlashes, and John Rice-Cameron – what else did I learn throughout the research process?

In Strangers in Their Own Land, Arlie Russell Hochschild describes how she learned to scale empathy walls – biases that restrict us from putting ourselves in the shoes of someone whose views do not align with our own and whose positions we find misguided at best and irrational and harmful at worst. Discussing politics and college culture with someone who is part of an organization whose views and publicly held positions I find deeply troubling was in fact an enriching and humbling experience. I was particularly moved by a Stanford College Republican differentiating between what he calls “compassionate Republicans”64 and Trump Republicans. All of us, live in echo chambers that consistently reinforce our worldview. Thus, we tend to perceive what we see as “the other side” as a homogenous group, something psychologists call the “out-group homogeneity effect.”65 We leave no room for nuance, complexity, heterogeneity, in short, we leave no room for humanness. Especially with regards to the dehumanization I noted in the Stanford College Republicans’ language, I learned to ask myself critically whether I do the same at times when speaking of “the other side.” Upon reading Strangers in Their Own Land, Laura Saponara summarized this feeling perfectly:

“I don’t think of myself as someone who dehumanizes people, but I found, in reading this book, that I do, by not seeing our fellow ‘strangers in their own land’ as whole people. I found empathizing with them to be challenging […]. But coming to grips with their feelings is far more interesting and gratifying than I anticipated.”66

Most media portrayals tend to also draw the picture of homogenous groups lacking diversity of thought and focus on the extremes only. The extreme increases an articles’ or a show’s views and clicks, but extremes do not show the full picture. Said Stanford College Republican and I spoke about the murder of George Floyd and his opposition to the Stanford College Republicans’ official position of supporting Trump’s use of force against protesters, about how Trump support was a result of fear – the fear of losing power. Speaking with someone who thoughtfully and calmly explained his reasoning and perspective, asking questions rather than articulating my own views, helped me leave my own echo chamber for a bit. Do I support Stanford College Republicans’ views? Absolutely not. However, I did learn to be more aware of the heterogeneity that characterizes the group and this nuance puts their humanness at the center, making empathetic conversations easier and more fruitful. As Arlie Russell Hochschild puts it in the preface of Strangers in Their Own Land:

“We, on both sides, wrongly imagine that empathy with the “other” side brings an end to clearheaded analysis when, in truth, it’s on the other side of the bridge that the most important analysis can begin.”67

I hope we can learn to disrupt each other’s echo chambers, and meet one another with empathy while keeping and strengthening our ability to think critically and drawing the line right where the dehumanization and exclusion of people whom we consider to be different begins. Here is to tearing down walls of empathy.

1Jeremy Adelman, ‘What is Global History Now?,’ Aeon, March 2, 2017, https://aeon.co/essays/is-global-history-still-possible-or-has-it-had-its-moment.

2Arlie Russell Hochschild, Strangers in Their Own Land: Anger and Mourning on the American Right (New York: The New Press, 2016).

3Pippa Norris, Cultural Backlash: Trump, Brexit, and Authoritarian Populism, (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2019), 3.

4Stanford Office of the Provost, “Provost’s Statement on Diversity and Inclusion,” Stanford Office of the Provost, accessed August 25, 2020, https://provost.stanford.edu/statement-on-diversity-and-inclusion/.

5Blanca Garcés-Mascareñas and R

inus Penninx, “The Concept of Integration as an Analytical Tool and as a Policy Concept,” in: Blanca Garcés-Mascareñas, and Rinus Penninx (eds), Integration Processes and Policies in Europe, (Heidelberg/New York: Springer, 2016), 11.

6Jeffry Frieden, “The Politics of the Globalization Backlash: Sources and Implications,” GRU Working Paper Series, March 1, 2019, https://www.cb.cityu.edu.hk/ef/doc/GRU/WPS/GRU%232018-001%20Frieden.pdf.

7“Backlash,” The Cambridge Advanced Learner’s Dictionary and Thesaurus [online], accessed August 14, 2020, https://dictionary.cambridge.org/us/dictionary/english/backlash.

8Roxy Bonafont and Jack Herrera, “John Rice-Cameron Wants to Make Stanford Great Again,” Stanford Politics, May 18, 2018, https://stanfordpolitics.org/2018/05/28/john-rice-cameron-make-stanford-great-again-1/.

9Carlos Eduardo, “Max Weber e o átomo da sociologia: Um individualismo metodológico moderado? [Max Weber and the atom of Sociology: A moderate methodological individualism?],” Civitas – Revista de Ciências Sociais, 16, no. 2 (2016), 326, quoted in Carlos Miguel Ferreira and Sandro Serpa, “Micro, Meso and Macro Levels of Social Analysis,” International Journal of Social Science Studies 7, no. 3 (2019), 121.

10Mackinac Center for Public Policy, “The Overton Window,” Mackinac Center for Public Policy, accessed August 20, 2020, https://www.mackinac.org/OvertonWindow.

11“Liberal,” The Cambridge Advanced Learner’s Dictionary and Thesaurus [online], accessed August 14, 2020, https://dictionary.cambridge.org/de/worterbuch/englisch/liberal.

12“Conservative,” Merriam Webster Dictionary [online], accessed August 14, 2020, https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/conservative.