Introduction

How does the northern German town Ahrensburg deal with its colonial past nowadays? This was the research question to embark on an oral history project and asking residents of this town what they think about Ahrensburg’s colonial history. It was challenging that not many residents are familiar with the fact that the town has a colonial history. In fact, there is not just a colonial past but also a colonial present as the town has buildings which qualify as colonial legacy.

Ahrensburg fails to recognize the structural relations between its own history and colonialism. This means the reality that the Schimmelmann family who lived in Ahrensburg from 1759 to 1938 owned sugar plantations in the Caribbean from 1763 to 1878 which were worked by slaves and the profits were transferred to Ahrensburg.

Given the fact that buildings were erected with this money and the family immensely shaped the town’s history, Ahrensburg’s present can only be understood by taking colonialism into account. In Global History concepts like “memorial sites of colonialism” by Jürgen Zimmerer which stress how seemingly European buildings only became possible because of colonialism, need to be deployed for buildings in Ahrensburg.[1] Speaking in Serge Gruzinski’s words, understanding contemporary Ahrensburg by looking at its history can only be done by approaching its past globally.[2]

The history of Ahrensburg mainly circles around an old building: castle Ahrensburg. This castle was owned by the Schimmelmann family who were not only slave traders and slave owners but some of the family members were also important Danish state’s men. Other representatives of the family supported famous German poet Friedrich Schiller or Matthias Claudius. The castle in Ahrensburg was visited by the Danish King and Otto von Bismarck. For some residents this collection of curiosities offers a presentable historic narrative. One that gives them a feeling of belonging and being proud of their hometown which has become rather a suburb of Hamburg and is economically dependant on this big city.

These narratives do not leave a lot of room to the colonial aspect of Ahrensburg’s history. This is nothing to be proud of. But instead of admitting or accepting that this is a part of the town’s history as well, some people prefer not to talk about this dark chapter of history and look for excuses why slavery and colonialism are just a minor and irrelevant aspect of the town’s history. A common excuse is that the Schimmelmann family only played a subordinate role in global slave trade and colonialism. It is being said that there are other cities in the state Schleswig-Holstein which have a more obvious colonial past. Of course, this is true, but this should not be an excuse in any kind of discourse but a research assignment for others. The Schimmelmanns and their descendants owned manors in several locations like Lindenborg, Wandsbek, Copenhagen, Emkendorf and Knoop. It would be important to also conduct more research on other places and buildings the Schimmelmann family owned and of course there are also other families, places and regions where there is a need to shed more light on this particular chapter of history.

Looking at connections between a small town, the phenomenon of colonialism and the intertwinements of the global and local context, border crossing seems to be addressed quite directly. However, for many citizens of Ahrensburg border crossing could mean to develop a new understanding of history which they perceive as being their history. Overcoming notions of guilt and experienced responsibility for having a great hometown with a great history and maybe crossing the social border of accepting that Germany has a colonial past and especially Schleswig-Holstein has a colonial past which dates back to the time it was part of Denmark.

As I have grown up in the town of Ahrensburg it was easier to gain access to people to conduct oral history interviews. I followed the town’s newspapers and looked at all the history publications about the town I could get a hold off. This research paper aims to sum up the historiography and oral history interviews. Of course, it will be necessary to describe the town to outsiders and to look at the history of the family Schimmelmann as well.

Germany’s colonial history is often being transfigured and not just in Ahrensburg this aspect of history is unknown and only reluctantly spoken about. Especially summer 2020 during heated debates and protests on racism and colonialism is a good moment to look at histories of seemingly local settings and to expose their global and colonial aspects and show that this has consequences until this day.

Contemporary Ahrensburg

Ahrensburg is a small town at the north-eastern border of the city of Hamburg. It currently counts a population of 34,554.[3] It has a regional train and subway connection to Hamburg and many residents work in Hamburg and visit the big city for cultural institutions, shopping or other events. Besides the fact that Ahrensburg is part of the state of Schleswig-Holstein and Hamburg is an independent state, it could be described as a typical suburban region. There is not much going on and many people are living in their own homes surrounded by a garden. One might say people want to live in peace and do not be bothered by anything.

Asked what is special about Ahrensburg and for what the town is renowned, people will most certainly mention the castle. While the cultural and political life is not very rich, the town’s nickname is “Schlossstadt” which would translate to castle town.[4] The castle represents Ahrensburg like nothing else, culminating in a statement by mayor Michael Sarach, “Without the castle Ahrensburg is meaningless”.[5]

The town’s topography needs some explanation in order to understand why the town does have a colonial legacy and which buildings might be affected. This concerns the castle itself as a “memorial site”[6] but also the local event location Marstall, a former horse stable built by Ernst Schimmelmann in 1845.

The castle itself was built in the end of the 16th century in the Renaissance époque by the Rantzau family. It is a quite exceptional building in Schleswig-Holstein and maybe therefore it is called a “castle” exaggerating its own meaning and the meaning of Ahrensburg a bit, while the building is by definition a “Herrenhaus” (manor house).[7] As the building is commonly known as castle and nobody would talk of a “Herrenhaus”, it shall be called “castle” throughout this work.

The building belonged to the family Schimmelmann from 1759 until the 1930s when the family had to sell all their property.[8] Today the castle is managed by a foundation which receives public money of the federal Republic of Germany, the state of Schleswig-Holstein and the town of Ahrensburg. Furthermore, many private donations as well as by businesses ensure the subsistence of the castle. Among these donors there is also a supports association [Freundeskreis] run by wealthy citizens of Ahrensburg.[9] The foundation manages a museum which is publicly accessible. Beside being a museum, the castle offers many possibilities to organize events in its interior. It is possible to have a wedding there, all kinds of parties including birthday parties for children with “fairytale-paperchases” as well as concerts and events like open air cinema in the park surrounding the castle.[10]

The Marstall is located in front of the castle approximately 100 meters away. It is used for theater performances, concerts, political events and other cultural events. It can also be rented to host conferences or celebrations of all kinds.[11]

Furthermore, there is a street named after the family Schimmelmann, the Schimmelmannstraße. According to Angela Behrens, the town’s archivist, the street was named after the family on September 30th 1932 after the family sold all their lands including the strip where the street is today.[12] However, the street’s name is almost all the time associated with Heinrich Carl Schimmelmann, the first and most popular Schimmelmann who lived in Ahrensburg.[13] In addition, the street was already registered on the internet platform tearthisdown.com, which calls to remove street signs that honor colonialists.[14]

Ahrensburg’s current topography cannot be explained without the presence of the family Schimmelmann who lived in castle Ahrensburg for about 170 years. Even though the castle was not constructed by this family, the Schimmelmanns gave it its current shape and preserved it by extensive renovations.[15] In order to understand this link some light needs to be shed on the family itself, their connection with the town of Ahrensburg and especially their most famous member: Heinrich Carl Schimmelmann.

Historic Ahrensburg

The Schimmelmann Family and Ahrensburg

The Schimmelmann family lived in Ahrensburg for about 170 years and only had to sell their property, beginning at the end of the 1920s due to economical challenges.[16] As lords of the manors the family had a great impact on the development of the town and influenced its current shape. The first lord of the manor was Heinrich Carl Schimmelmann, a rich merchant who had great plans with Ahrensburg. He had bought the manor in 1759 from money which he had earned by different ventures like supplying the Prussian military in the Seven-Year War, auctions of Dresden china which he had obtained to a very low price from Frederick the Great, King of Prussia and the production of counterfeit money.[17] However, as Christian Degn has pointed out, the final payment for the castle and manor was only made in 1768 when Schimmelmann already owned slaves and plantations which he had bought in 1763.[18] Already in 1767 he earned a good amount of money with his sugar plantations.[19] This fact provoked a debate whether the castle was partly financed with money earned through slavery.[20]

Ahrensburg belonged to Denmark at the time and Schimmelmann hoped to enter the Danish aristocracy. It was not very typical for a civil person to become lord of the manor and “owner” of serfs who lived on the manor. But maybe a representative manor would be the ticket to an office at the Danish royal court. Schimmelmann had earned a reputation as a very rich merchant and indeed the Danish King contacted him and gave him a noble title and even made him his treasurer.[21]

To illustrate H.C. Schimmelmann’s impact on Ahrensburg’s topography, which was called Woldenhorn until 1867 and only later named after the castle, it is interesting to look at three maps. One shortly before Schimmelmann bought the manor and one from 1766 showing the reformation of the whole village. In fact, the changes Schimmelmann made are still obvious on a contemporary map.

The first map shows the area that is central Ahrensburg today in 1749, when the manor still belonged to the Rantzau family. The second map has the same perspective but a wider focus. However, it shows the significant changes in the topography created by the building measures by H.C. Schimmelmann. Woldenhorn did not look like a small farming village anymore but had become a representative and symmetrical park area according to baroque standards. The one main street leading to a circle rotary where three streets lead into different directions, is still the main street today and the other streets are also still at their place today and important avenues leading towards the city center. Even the trees planted along the avenues are still standing there.[22]

It was only the great-grandson of H.C. Schimmelmann, Ernst Schimmelmann who conducted important building measures in the town again. He was the lord of the manor from Ahrensburg from 1844 to 1882 and thus member of the fourth and last generation of the Schimmelmanns who owned slaves and the plantations. The Marstall was just a horse stable for E. Schimmelmann but its significance for Ahrensburg has changed a lot over time. It is next to the castle one of the landmarks Ahrensburg uses to represent itself. It was built in 1845/46.[23] About ten years later the castle itself was extensively renovated and also other buildings on the manor were mended and renovated.[24]

More than 250 years after the Schimmelmann family had moved to Ahrensburg their traces are still very well visible and thus their history is deeply connected with Ahrensburg’s history. However, the Schimmelmann family’s importance surpasses the local context of Ahrensburg.

The Schimmelmann family and colonialism

LASH 127.3 62 I. Photographed by the author.

LASH 127.3 62 I. Photographed by the author.

Ahrensburg’s history and the history of the family Schimmelmann could also be told from a different perspective. While the former chapter focussed on the local level, there is also a global aspect. The Schimmelmann’s and Ahrensburg’s history is deeply connected with colonialism.

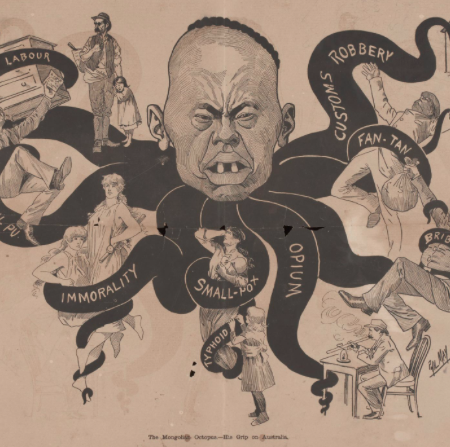

Thus, family Schimmelmann’s significance exceeds the local context of Ahrensburg.[25] In several radio-interviews historian Jürgen Zimmerer compared H.C. Schimmelmann to the famous slave trader Edward Colston, whose statue was toppled in Bristol on June 7, 2020.[26]

„[H.C.] Schimmelmann is a highly interesting figure here in Hamburg. His history is very similar to Colston’s. Schimmelmann presented himself as a benefactor but he had partly earned his fortune as one of the biggest slave owners in the Caribbean.” [27]

Born in 1724 as the son of a small civic merchant in Demmin which is in the northeast of Germany today, his path was not marked to become Danish treasurer and one of the richest persons in the kingdom.[28] Heinrich Carl Schimmelmann cheated his way up, driven by his greed for more money, he frequently entered new business ventures and always focussed on his own advantage.[29] He very successfully managed to consolidate his political career with his private economic interests.[30]

As early as 1753 H.C. Schimmelmann started trading products originating from colonies, like sugar, tobacco, and coffee in Dresden. However, he did not own plantations at this point.[31] After Schimmelmann had moved to Ahrensburg, the King of Denmark who was King of an almost bankrupt kingdom, asked Schimmelmann to work for him and finally becoming his treasurer. Schimmelmann already had a reputation as a competent merchant. He suggested to the King that he should sell the crown’s sugar plantations on the Danish West Indies.[32] And it was Schimmelmann himself who bought four plantations from the King and the only sugar refinery in Denmark which presented an excellent business opportunity at that time.[33] This seems to have been a typical move for him. He did not distinguish between his private affairs and his office as treasurer and bought the plantations which were deemed some of the best in the Danish West Indies to a “very favorable price”[34]. In 1763 there were about 400-500 enslaved people working on Schimmelmann’s plantations.[35] Just ten years later there were about 1,000 slaves on his plantations, culminating in 1,028 slaves in 1782.[36] These numbers show that H.C. Schimmelmann had bought many more slaves compared to the point he had acquired the plantations.[37]

As a merchant Schimmelmann had many businesses such as his three manors with different factories in Holstein and in Jutland and a weapons factory. Moreover, he made international financial trades and he was a slave trader.[38] Klaus Weber calls H.C. Schimmelmann just one of the few German slave traders who reached a scoop such as the Romberg family, who owned one of the biggest slave trading businesses in Bordeaux in the end of the 18th century.[39] Schimmelmann was a big shareholder of different slave trading companies. Such was his influence that 14 ships were named after him or his wife and children. Some of the ships were his own and some belonged to the companies in which he was one of the most influential shareholders.[40] As H.C. Schimmelmann died he was probably the richest person in the Danish kingdom as he was the one who paid the most taxes per capita in Denmark.[41] He combined his wealth in a trust[42], which he inherited to his children. “The Count Schimmelmann Family Trust” consisted of Schimmelmann’s manors Wandsbek, Ahrensburg and Lindenborg, as well as a townhouse in Hamburg and one in Copenhagen. Moreover, there were the most valuable assets, the sugar plantation as well as the sugar refinery, the weapons factory and many other assets like shares, securities and more than a dozen ships.[43]

The manors and interests from the trust ensured his descendants wealth for a long time as it existed until it had to be dismantled by German law in 1929.[44] As the plantations were part of the trust until they had to be sold in 1878, his descendants took advantage of slavery and the money earned with slave trade for more than a century.[45]

“The sugar refineries and the many other derivative effects of the trade in sugar and slaves played a significant role in the economy of the capital and in the entire Danish-Norwegian area, including Schleswig and Holstein.”[46]

However, the economic impact of colonialism is often underestimated and it is claimed that the heirs of Schimmelmann did not receive much money from the trust in the 19th century.[47] For instance, Carl Schimmelmann (1787-1833), the grandson of H.C. Schimmelmann who was lord of the manor in Ahrensburg from 1809-1833, faced some economic difficulties on the manor during the Napoleon-wars but he still had a steady income from the trust his grandfather had inherited him.[48] At this time there were still more than 900 slaves working on the plantations of the family.[49]

As of 1844 the Schimmelmann family in Ahrensburg were the only remaining Schimmelmann-heirs of the Schimmelmann trust. [50] The revenues from their plantations which were still worked by slaves in the 1840s were almost completely transferred to Ahrensburg. As Ernst Schimmelmann (1820-1885) took over the manor in Ahrensburg in 1844, the family continued to have a steady income from their plantations. [51]

The revenues from the plantations were higher than usual as E. Schimmelmann built the Marstall and were extraordinary high in the 1860s when he had only recently renovated the castle.[52] The trust founded by his great-grandfather’s wealth still ensured Ernst a higher living standard than most of the other noble families at this time. Besides the plantations they also received money from their manor Lindenborg in northern Denmark and from selling their manor in Wandsbek in 1857. According to Angela Behrens Ernst’s rule in Ahrensburg can only be understood by having his big wealth in mind. This money was not only used for personal expenses but also transferred to the manor system to finance building measures.[53] Thus, money that was partly earned on the plantations in the colonies created jobs for local workmen and merchants. Behrens sums up that the decision of Ernst Schimmelmann to live in Ahrensburg as he also had other manors, had a “positive impact on Ahrensburg” which can be seen until today because of buildings like the Marstall, the renovation of the castle and last but not least that the railroad and road from Hamburg to Lübeck were built via Ahrensburg, and exist until this day. [54]

Historians like Degn, Gøbel or Krieger have mainly laid a focus in their research on two members of the Schimmelmann family: Heinrich Carl Schimmelmann, the first noble Schimmelmann, Danish treasurer and the rich merchant. The other Schimmelmann in historiography’s limelight is Ernst Schimmelmann (1747-1831), eldest son of H.C. Schimmelmann who inherited his title as a treasurer and functioned as finance minister and minister of foreign affairs to the Danish Crown. Ernst Schimmelmann is an important figure of the Schimmelmann family as he is renowned for abolishing the Danish slave trade in 1803. This caused some misconceptions in falsely suggesting that this meant the end of slavery in the Danish colonies.[55] Slavery only ended in 1848 in the Danish West Indies after an uprising of the enslaved people.[56] However, the from 1848 on formerly free plantation workers were only offered discriminating contracts with the plantation owners that forced them to carry on living in slave like conditions.[57] After the abolition of the Danish slave trade there was still an illegal slave trade which reached a similar scoop to the legal slave trade before and also could not be stopped as the British tried to internationally execute the abolition of slave trade.[58] In addition it was still allowed for the plantation owners in the Danish West Indies to trade slaves among the Danish Islands.[59] So using the formal abolition of slave trade as a fig leave is mostly a discursive tactic which does not consider the actual developments.

Ernst Schimmelmann is often portrayed as an idealist in opposition to his father. He was engaged in the enlightenment movement and gave a stipend to German poet Friedrich Schiller.[60] However, he was also director of the family trust and therefore slaveowner and slave trader himself. Instead of abolishing slave trade directly in 1792 the edict came in effect only in 1803 and the Danish government payed massive grants in the transition period to ensure that every plantation owner could buy enough slaves before the abolition formally came into effect.[61] All in all the Danish abolition has to be seen as economically driven as abducting people and trading them had become too expensive and it was regarded more profitable that slaves should give birth to as many children as possible to ensure the planters to have enough slaves.[62]

Talking about colonial traces which H.C. Schimmelmann left in Ahrensburg, it must be mentioned that he brought enslaved people to Ahrensburg. From 1765 on seven boys had to follow apprenticeships in the town to “expand their value”. They were baptised and confirmed in the local church.[63] Only a few of them eventually were brought back to the plantations were they had been born and some of this very young men died in Europe.[64] Another case were the so called “Kammermohren”, enslaved children who were considered “exotic” and worked as servants in castles and manors across the Danish kingdom. H.C. Schimmelmann “gifted” these children to his daughters who were married and lived in different manor houses in Denmark. At that time Black boys were a “prestige object”. Beside the Schimmelmann family the Reventlow family and von Baudissin family had a “Kammermohr” as Schimmelmann’s daughters had married into this families.[65]

On the other hand, there were skilled workers from Ahrensburg who worked on the plantations. At least one of them raped an enslaved woman on the plantations who got pregnant.[66]

In conclusion, Ahrensburg’s past does include economic effects from colonialism which have positive effects for the town until today. This concerns buildings and infrastructure. Next to this visible colonial legacy, there is an invisible colonial legacy concerning workers from Ahrensburg who worked in the colonies and especially enslaved people who were brought to Ahrensburg.

Ahrensburg’s contested past

Historiography

Historiographic writings about the Schimmelmann family have a strong focus on Heinrich Carl Schimmelmann, the first Schimmelmann in Ahrensburg. Since he took over the manor in 1759, people have talked and written about him. In the 18th, 19th and most of the 20th century these writings praise him and the “great things” he did for the town of Ahrensburg. Just in the 1970s some academics started to look at Heinrich Carl Schimmelmann and the other part of his complex biography. Id est that he was a slave owner, he traded slaves and he and his descendants even owned their own sugar plantations on the Danish West Indies from 1763 to 1878. However, many local history publications in Ahrensburg only look at H.C. Schimmelmann’s “fascinating” biography and his actions in Ahrensburg. Only recently there is a stronger interest in the colonial aspect of him. Nonetheless, his descendants are mostly left out of these narratives.

The first person to write about Heinrich Carl Schimmelmann was the local pastor at the time who wrote a chronicle. Pastor H. J. H. Eicke was in office from 1729 to 1773 and is according to the former archivist of the town of Ahrensburg, Christa Reichardt, the first chronicler of Ahrensburg.[67] He writes that Ahrensburg “is a paradise ever since Heinrich Carl Schimmelmann bought it.”[68] Also, everyone seemed to be very happy about the new lord of the manor and Eicke writes in euphoric words about the great changes, novelties and renovations the new owner of Ahrensburg undertook. He is very fond of new welfare measures and the donations Schimmelmann gives to the church.[69]

Another early article on Schimmelmann dates back to 1829. This paper was found and as well published by the former archivist Reichardt who writes in an introduction that Heinrich Carl Schimmelmann “is a man of outstanding significance for the history of the town of Ahrensburg.”[70] It is written by a doctor and teacher who worked for the Schimmelmann family in the early 19th century. He writes that Schimmelmann’s fortune was based on auctions of Dresden china[71] and mentions for the first time the plantations in the Caribbean, bot not the enslaved people.

Then there is a book first published in 1882 by H. Rahlf and E. Ziese who suggest that after Schimmelmann bought Ahrensburg, a new life began for the town. As evidence they infer that Schimmelmann’s predecessors had “run down”[72] the manor. They also stress that Heinrich Carl Schimmelmann gave the town its current shape (1882). However, they do not write about Schimmelmann’s private business activities.

According to Martin Krieger, currently professor for Northern European history in Kiel, there are many sources on the life of Schimmelmann but academics only started doing research on him relatively late.[73] There are some rather academic publications in the late 1930s about Schimmelmann. Hans Schadendorff, who is commemorated as the “saviour of Ahrensburg’s history” as he had bought the “Schimmelmann archive”, notes in 1935 that the “incredibly lucky societal rise of Schimmelmann lead to the production of some myths”.[74] But again the sugar plantations are only a note in the margin and Schadendorff rather focusses on Schimmelmann’s political life.[75]

An academic interest in Heinrich Carl Schimmelmann began around 1970.[76] The book which remains being the most impactful until today by Christian Degn, is a family biography of the Schimmelmanns which focusses on the international trade endeavours of the Schimmelmanns, particularly at the slave trade and slave possession and their political life.[77] What is problematic about this book is that it carries an entertaining narrative and therefore it remains unclear in some parts whether certain passages are rather myths or fairy tales, or based on historical research. He also upholds a hopelessly eurocentric perspective and does not write about slaves as being individuals.[78] He seems to be fond of a kinder and paternalistic treatment of enslaved people throughout his book – with white people leading them to their Christian enlightening – and in a new edition published in 2000 he uses the reference of Kofi Annan being UN-general secretary as evidence that “things are getting better”.[79] However, Degn uses a lot of sources and all following publications are based on the great deal of original research he conducted.[80]

Following the 1970s there are some local history publications by the Ahrensburg historical association[81], schools and pamphlets published for local historical anniversaries.[82] The tenor of these books is that they emphasize the importance of the family Schimmelmann for the town of Ahrensburg. Stressing that they set up a post office in the town, established a railroad, renovated the town and saved the castle from being broken off. Particular symptomatic for these examples is the notion, “’ein elendes Dorf blüht auf”[83] after Heinrich Carl Schimmelmann took over the town. However, Schimmelmann’s slave business is mentioned sometimes. Only recently there seems to be some focus on the trust Heinrich Carl passed on to his descendants and how renovations and buildings were payed for with this money.[84]

This new finding seems to go back to the outstanding work of the town’s current archivist Angela Behrens, whose very well researched dissertation Das Adlige Gut Ahrensburg von 1715 bis 1867 was published in 2006.[85] This book contains many sources and is the only published academic piece of research focussing on the town of Ahrensburg, but also including the family Schimmelmann’s personal history in the 19th century.

Only in 2013 Martin Krieger, professor for northern European history in Kiel published an article on Heinrich Carl Schimmelmann in a volume edited by Jürgen Zimmerer.[86] This volume particularly focusses on “memorial sites”[87] of German colonial history. Schimmelmann is the first person to be mentioned in the section “actors” thus, amplifying his importance in German colonial history.

A very recent article in the museum guide for castle Ahrensburg by Sonja Vogt “Schimmelmann and the Slaves” might seem a bit disturbing.[88] While evaluating the person Schimmelmann as a genius – historical reference remains unclear – his commitment into slavery and slave trade is being played down. In one paragraph the word “only” is being used three times, referring to Denmark’s “subordinate” role in slave trade.[89] In another phrase it is written that slaves on Schimmelmann’s plantations were treated in a humane way.[90] Then the two page article stresses that “African savages” were enslaved by “their own kind which lead slave traders to have a better conscious”.[91] Vogt ends her article with a reference to nowadays “slavery” and suggests a parallel between Schimmelmann’s slavery and the work conditions of garment workers today. All in all, this article can be seen as an attempt to rehabilitate Schimmelmann in a current debate and to distract people’s attention away from Heinrich Carl Schimmelmann. The article does not seem to be deeply engaged in relations between historical events. This becomes very clear when it stresses that Ernst Schimmelmann, the son of Heinrich Carl abolished the Danish slave trade.[92] Thus suggesting the chapter of “Schimmelmann and the slaves” ended with the abolition of the Danish slave trade in 1803. As others have pointed out that did not mean the end of slavery in Denmark and was rather rooted in economic concerns about slave transportation being too expensive. If Vogt’s article would have wanted to fully look at “Schimmelmann and the Slaves” it might have mentioned that the family of Schimmelmann owned slaves from 1763 until the revolution of 1848. It might have also wanted to answer why the then liberated slaves continued to work on the plantations of Schimmelmann and mention that the family just sold their plantations in 1878. Furthermore, the title of Vogt’s text stands in a dark tradition of European paternalism and objectification of enslaved people. Why does the title not give the name of enslaved people and mention Schimmelmann as “some European lord”?

Beside historical writings aiming to provide accurate and factual information, there is also some popular fiction on Heinrich Carl Schimmelmann, which could explain why there sometimes seems to be a mixing up between actual historical information and myths and fairy tales about mainly the first Schimmelmann in Ahrensburg, Heinrich Carl.[93]

Oral history interviews

The town of Ahrensburg is not the first and most likely also not the second guess if Germans were asked about colonial legacy. Even the inhabitants of the town would not imagine that their town might have something like that.

“I wouldn’t have come up with your research question myself. I mean first of all you would need to say that Ahrensburg has colonial legacy. However, I think humanities scholars always ask good questions.”[94]

It seems important to talk a bit about myself, the author. I lived in the town of Ahrensburg from my birth until I graduated from high school and left the town when I was 19 years old. However, I attended school in Hamburg and thus always lived a bit in between the city of Hamburg and the town of Ahrensburg. I think I got to know about Heinrich Carl Schimmelmann through von Baudissin[95], a classmate of mine whom I was also able to interview for this project. She is a descendant of the Schimmelmann family, and I could not believe her, when she talked about “the slaveholder from the castle Ahrensburg” for the first time. Talking about the family Schimmelmann is a sensitive matter for many residents. They do not really like to be confronted with this dark period of Ahrensburg’s history. Especially following the murder of George Floyd in the US which sparked world wide anti-racism protests and intellectual discussions, some officials in Ahrensburg were afraid to talk to me and some even had to decline as the topic appeared to be to sensitive for them. The fact that many interviewees asked to be anonymized further underlines that this is a highly contested and also controversial topic for many. People who had doubts talking with me but decided to do so often stressed the fact that I am a community member and therefore they would talk to me as an “Ahrensburger”.

Nonetheless the worldwide anti-racism debate did not just offer challenges to my project. Starting my interviews on the 10th July 2020 I had only three arrangements with possible interviewees. Only five days later I had conducted nine interviews and spoken to many other people as I had really arrived in my hometown at a time when Ahrensburg started engaging in one of it is most lively debates about Schimmelmann and (colonialism) since years. Christian Schubbert-von Hobe, chairmen of the municipal education, cultural affairs and sports committee had proposed to check all the street names in the town whether they were still appropriate to nowadays standards. This proposal came to public attention in some newspaper articles on the 10th of July, the date I conducted my first two interviews.[96] Already on July 1st the local deputy for Schleswig-Holstein’s state assembly Tobias von Pein had caught public attention in claiming that there is a need for discussion about colonialism in the county of Stormarn of which Ahrensburg is part of. Schubbert and von Pein particularly mentioned Heinrich Carl Schimmelmann in their statements.[97]

One reason for von Pein’s statement might be a debate in the state’s assembly in which Schimmelmann was one of the few persons from Schleswig-Holstein mentioned who were engaged in colonialism.

“In Great Britain protesters toppled statues which were erected to honor local philanthropists like Edward Colston or Robert Milligan. What was forgotten as their statues were erected, was the undeniable fact that they had earned their fortune with slave trade. This is not just an English phenomenon. If you look at the family Schimmelmann in Ahrensburg for instance, it’s the same. People should think of this when they enjoy a visit of their castle in Ahrensburg.“[98]

The interviewees are all rather affluent and White residents of Ahrensburg. Ahrensburg’s debate is very self-referential, barely anyone spoke about “Schimmelmann’s slaves” as individuals, as people. It is about the reputation of Ahrensburg and sustaining “great cultural monuments” like the castle. Thus, the oral history interviews in this project need to be seen and categorized as representing the majority group of Ahrensburg.

Most of the interviewees are people who have some knowledge of the town’s history and are rather educated. These are a former member of the castle support’s association, politicians, a blogger, museum staff, a descendant of the Schimmelmanns and other citizens.

First of all, I spoke with my grandfather, Dieter Blank, who has been a resident of Ahrensburg since 1987. What made me interview him was the fact that he is a former member of the support association for the castle Ahrensburg.[99] He said he joined the association in 1995 because one of his bosses at his job pressured him to do so.

“A financial manager in my company who lived on a spaciously estate in Ahrensburg was chairmen of the association and he tried to coerce everyone he could get hold off, to join the association. I don’t think I would have joined the association if it wasn’t for my boss.” [100]

After being retired Dieter Blank left the association which he had not joined because he believed in the cause but to not annoy his boss.[101] As he can recall the cause of the association was mainly to collect money for the restoration of the castle and its interior. They did not deal with the history of the building or its inhabitants.[102] Blank remembers coming across Schimmelmann as a “negative example” ten years ago when a monument for Schimmelmann should be erected in Wandsbek, a district of Hamburg.[103] Following protests the monument had to be deconstructed after two years.[104]

“Basically, this was the first time that it came to my attention – besides the fact that Schimmelmann was a rogue at his business activities – that he was one of the world’s leading and biggest slave traders.”[105]

Asking friends or neighbors, Blank does not have the impression they know much about Schimmelmann’s colonial business activities and he also does not recall that this topic was mentioned at guided tours in the castle in which he participated.[106]

On the same day I met with Harald Dzubilla, resident of Ahrensburg since 1968, who lives in Schimmelmann Street. Dzubilla has a blog in which he writes daily entries about the social and political life in Ahrensburg.[109] As a resident of Schimmelmann Street he is very upset about the fact that his street is named after a slave trader.

“I am trying to change things in Ahrensburg with my blog and to show people that you cannot name a street after this count Schimmelmann.”[110]

However, he found his way dealing with his address. “When I get home and have to read ‘Schimmelmannstraße’ or someone asks me for my address, I always add that my street is the slave trader’s street. That’s how I call it.”[111] Dzubilla is glad about the public attention for his street through the two politicians Schubbert and von Pein. He argues that museum staff in the castle only deal with the slave business of the family Schimmelmann “alibimäßig” (to have an alibi) and it was only mentioned marginally.

“The prominent display of a picture showing Schimmelmann in the castle tells me that the museum staff don’t get it. For me this painting is not supposed to be there. I would put it in the broom closet.”[112]

He suggests exhibiting pictures and graphics from the book Die Schimmelmanns im atlantischen Dreieckshandel[113] by Christian Degn showing the cruelty of Schimmelmann’s slave business. “Why do we not honestly admit: ‘That’s the way it was?’”.[114] Nonetheless, Harald Dzubilla mentions that Schimmelmann did good things for the town, adding that he did this for his own advantage and that despite his contributions for the town, he should not be honoured in any way.[115]

Dzubilla accepts the fact that castle Ahrensburg has become a landmark for Ahrensburg. The town would not have more to offer. He does not think it should be torn down as it was constructed by the Rantzau family.[116] He shares my impression that most of the residents of Ahrensburg are not interested in the debate circling the castle, the Schimmelmanns and colonial legacy.

“90 percent of the town’s population want to live in peace and have good television programme. Of 35,000 citizens only around 10 people attend the town’s council meeting. That shows the interest of people. Therefore, politicians can do what they want because nobody is holding them accountable.” [117]

The next day I had the chance to talk to my friend, a descendant of the von Baudissin family. As one of Heinrich Carl Schimmelmann’s daughters married an ancestor of hers she is a great- great- great- great- great- great grandchild of Heinrich Carl Schimmelmann. Von Baudissin does not live in Ahrensburg but in a quarter in Hamburg which is not very far away. She never visited castle Ahrensburg.[118] Yet, the history of her family is not a very much present topic in her family. Nonetheless, they own the book by Christian Degn[119] and are aware that their ancestors were engaged in slavery. Particularly her father told her in her childhood that it is a privilege to be able to trace back her ancestors to the 11th century but most of them are known for things one should not be proud of. [120]

Von Baudissin feels that it was her responsibility to make people aware and remember that her ancestors lived of the exploitation of other people.[121] I thought it was interesting to ask her if she senses some kind of guilt for the actions of her ancestors, as some people in Ahrensburg evoked the impression they felt personally attacked by talking about the Schimmelmanns under the light of colonialism.

“I don’t sense any kind of guilt. That’s not right. I don’t have anything to do with that. However, I feel responsible to talk about this past and make people aware of it by having this interview for instance.”[122]

Later on that day I met with my neighbor Bjorn Nielsen[123] who worked as a municipal civil engineer for the town of Ahrensburg upon being retired. He has lived in Ahrensburg all his life and was born in 1938. He recalls that his grandfather worked for one of the count Schimmelmanns and does not remember being told by his mother or having heard of the fact that the family Schimmelmann’s revenues from colonialism were significant for the prosperity of the family or the town.[124] Nielsen does not like the proposal to rename Schimmelmann Street.

“Why should we erase that name? The reason why the street got its name was probably that Schimmelmann was the owner of the land the street was built on. Rantzau who owned the manor before Schimmelmann also got a street named after him in this area. These naming practices were very common when new quarters were planned. If Schimmelmann should be commemorated at the time then it was for the things he did for Ahrensburg and his outstanding importance for the town. However, not for his successful participation in the dark chapter of the slave trade. He didn’t invent slave trade nor enact it. By buying Danish plantations he took over the slaves who were already working there and as a hardworking and genius merchant he extended his business. At the time that was nothing unhonourable, like the serfdom here in Europe which was also used by the Rantzaus. I hope that slavery worldwide in all its forms is over. In an Wikipedia article on Schimmelmann I found him foremost labelled as a slave trader.[125] Slave trading was just one part of his actions. Commemoration should be conducted in a balanced way.” [126]

Nielsen sees problematizing Schimmelmann’s colonial ties as driven by nowadays “zeitgeist”.[127] He has the impression notions of guilt are constructed concerning Ahrensburg’s connection with the family Schimmelmann. If Ahrensburg would “completely erase the name Schimmelmann, the possibility to commemorate his less honourable actions” would be lost.[128]

I then talked to another neighbor Ilse Groot, who has lived in the town of Ahrensburg since 1965. She does not know much about the family Schimmelmann and rather recalls some historical stories about the neighborhood, were the counts Schimmelmann owned a foresters house until they left Ahrensburg in the 1930s.[129] She visited the castle long time ago and thinks maintenance of the building is very expensive for the town, as the castle is only relevant for tourism according to Groot.[130] Her grandchild, Benjamin Groot, who was born in 1992 and attended primary and secondary school in Ahrensburg recalls learning about the family Schimmelmann in school but not about slave trade or in relation with colonialism.[131]

Dr. Anastasija Zwetkowa[132] is a leading staff member of the museum in castle Ahrensburg and the foundation for castle Ahrensburg. For this interview she chose to be anonymized. Sitting in the castle I first of all asked her how she would assess the meaning of Heinrich Carl Schimmelmann for the town of Ahrensburg.

„We don’t know if the castle would still exist if it wasn’t for Schimmelmann who bought this house in 1759. It was already almost 200 years old and rocked down very much by the family of Rantzau who possessed it before and stood in frequent conflicts with the local population.” [133]

Zwetkowa praises the good things the family Schimmelmann did for the town of Ahrensburg. Thanks to them a post station was introduced in the town and later on they could manage to get a railroad connection for the town. Thanks to them “modernity arrived in Ahrensburg” [134] Mainly Heinrich Carl Schimmelmann tried to establish businesses in Ahrensburg and he introduced vaccinations for the population.[135]

Extensive renovations and the construction of the Marstall among other buildings provided work for the local population, according to Zwetkowa who describes the family Schimmelmann as an important employer in the region for the profit of the local population who had jobs.[136]

It seems to be important for Zwetkowa to emphazise that Heinrich Carl Schimmelmann did not buy the castle with money originating from slave trade.

“It’s definitely not true that the castle was paid for with money earned with slavery. That is very often being overlooked in this current debate which is mainly emotional.”[137]

A very important question for Zwetkowa is, how she deals with the fact that the Schimmelmanns possessed and traded slaves in the museum. She told me that she does not like putting signs or notes on the wall to not destroy the “illusion that the castle is still inhabited”.[138] Therefore, historic information is provided through Audio Guides which are available in German and English. She has been struggling while revising the German audio guide how she should deal with the aspect of slavery. She came up with the solution to let Heinrich Carl Schimmelmann speak for himself.

“We are using different voices for the audio guides and Schimmelmann speaks about his slave trade saying, ‘many people traded slaves back in my days’. Objectively this is correct. Of course, he cannot question himself. We could have added, ‘nowadays we would do that differently’ or something like that. But I thought that was stupidly admitting to the current zeitgeist and I thought we are already dealing with this topic on many scales and very differentiated that I didn’t want to let him talk in this political correct way.”[139]

Asked if Zwetkowa thinks if it was important to exhibit Schimmelmann as a slave trader and somebody involved in colonialism, she said that she thinks she is obliged to do so. However, she does not want to adapt to dominant trends. “Especially in context to this debate on colonialism I want to warn people to adapt to nowadays moralized point of views.”[140] She also experiences criticism of Schimmelmann and “her” castle as unfair. Everything should be looked at critically not just Schimmelmann.[141] In particular, she mentions two other manor castles in Schleswig-Holstein, Emkendorf and Knoop. These buildings were built by two of Heinrich Carl Schimmelmann’s daughters and directly financed by money earned with slavery.[142]

Concerning the current debate on colonialism Zwetkowa stresses that, “we are not better nowadays and consuming products manufactured under very bad labour conditions”.[143] She seems to want to say that “we are not better than Schimmelmann” referencing modern slavery.[144]

Another interview was with my sister, Lara Marie Haude, born in 2009 and thus 71 years younger than the oldest interviewee of the project. She visited the castle several times already as she played the piano at concerts organized by her piano teacher as well as birthday parties in the castle.[145]

Tobias von Pein is Ahrensburg’s deputy for the state’s assembly of Schleswig Holstein and member of the German Social Democratic Party (SPD). As I read in a newspaper article[146] that he mentioned that there is a need for a discussion on colonialism in Ahrensburg, I was very eager to find out what he meant with this notion.

“Taken into account that there currently is a debate on racism in the US as well as in Germany it becomes obvious to me that Germany has to engage more thoroughly with its past – this being colonialism slavery and in particular the expropriation of other countries and their population. We need to reappraise our past and make it accessible to society that people are able to learn something for today. Thus, we will be able to fight racism and exclusion.” [147]

Asked what he thinks about the way history is being presented in the museum in castle Ahrensburg, he expresses criticism. Von Pein has the impression some parts of history are purposely being left out or sidelined and the castle is presented as a “fairy-tale castle”. [148]

“I do not like that this time period is being romanticized. Of course, it is always a challenge for a place like a castle to show how things looked in former times but to also contextualize the past. I think the castle misses historic contextualization. They display the history of the building and what happened in the past. It is a bit like travelling back in time. I am missing this contextualization and link with today. Schimmelmann has a dark side as well, referring to exploitation and slave trade – aspects which should be highlighted. Even though these things are mentioned in the exhibition, this happens in an evasively way. I don’t see any reference to today and that these things are still relevant today; for instance, for Black Germans.” [149]

Mr. von Pein supports an open debate and stresses that street names were always intended to honor a person. “Street names aren’t carved in stone, therefore we should have a discussion and ask ourselves if we still want to have certain street names in a democratic Germany in 2020.”[150] Furthermore, he notes that the town of Ahrensburg does not have a public place or any kind of memorial to remember the enslavement and slave labour forced upon thousands of people by the family Schimmelmann.

“Maybe we could have a memorial which publicly informs which important political decisions were taken in Ahrensburg. I mean, we don’t know if it was decided at the coffee table in castle Ahrensburg to sell certain people to some places.” [151]

As native person from the state of Schleswig-Holstein, which was a part of Denmark until 1866 it is important for von Pein to look at colonialism before the foundation of the German Reich in 1871. For him, this part of history should be more in the limelight and be talked about. [152]

Christian Schubbert-von Hobe is chairman of the municipal committee for education, cultural affairs and sports and member of the Green Party in Ahrensburg.[153] The interview focussed on the motion he had brought to the municipal committee for education, cultural affairs and sports. This motion mentions Heinrich Carl Schimmelmann and suggests reviewing all the streets in Ahrensburg which might be named after “critical” personalities. It proposes a committee which should reassess these personalities with academic expertise. I asked Schubbert why he filed the motion.

“We used to prepare important subjects in committees, and I had the idea to do the same with street names. And this topic really jumped at us. On the one hand because of the American debate on colonialism, on the other hand because a school’s principal rejects to put up new signs for the event location ‘Alfred Rust Saal’.” [154]

Schubbert thinks that it would make up for a good image if Ahrensburg could show outsiders, that the town deals with its past and history.[155] According to him street names like Schimmelmannstraße honor people in the present.[156] Even though, this street was named after the family, people would always associate Heinrich Carl Schimmelmann, the slave trader with this street name. [157] Schubbert poses the rhetorical question why Ahrensburg should always avoid having debates on these subjects and opposes an attitude stating that the town would have better things to do.

“I really think we should critically look at all the street names from time to time. Are these really personalities we still want to name a street after? I think the last time the names were reviewed was in 1945.” [158]

Unfortunately, I was not able to formally interview all the people I would have liked to. However, national German public radio broadcaster Deutschlandfunk interviewed two interesting people. The radio show which was broadcasted on August 3rd, 2020 was part of a compilation on disputes about monuments and asked if the ongoing debate on colonialism had arrived in Ahrensburg.

Angela Behrens is the archivist of the town of Ahrensburg. As employee of the town she did not get the okay of the mayor for being interviewed for my project. Apparently, the family Schimmelmann is a political sensitive topic for the town’s officials. In the radio interview she said:

“It is currently challenging for the town of Ahrensburg and always has been a challenge for the town to have had a connection with the family Schimmelmann.”[159]

According to her the connection between the town and the family Schimmelmann had advantages and disadvantages and that every time period found different ways dealing with this.[160] Behrens stresses that it would be vital in a democracy to critically reflect on if it was still appropriate to honor certain personalities e.g. with a street name and by doing this setting the course for the future.[161]

The radio show also featured an interview with Dirk Müller-Brangs, chairman of the local historical association and retired history teacher in Hamburg.

“Many things can be said about Schimmelmann historically but Ahrensburg wouldn’t be possible without Schimmelmann. Ahrensburg wouldn’t exist without Schimmelmann and the town should be grateful that it is how it is thanks to Schimmelmann. This new iconoclast- [“Bilderstürmer”] debate is awful and unnecessary. We already had this discussion and it is not the first time that we are talking about certain names.”[162]

Another member of the historical association has done a lot of research on Heinrich Carl Schimmelmann and visited many archives. He answered my questions via e-mail and asked to be anonymized. I questioned him why he conducts research on Schimmelmann.

“There are many false information about the life and work of Heinrich Carl Schimmelmann. I won’t be able to change this, but I will do the best I can with my research.”[163]

According to him Heinrich Carl Schimmelmann had done many good things for Ahrensburg and one should be careful in assessing and contextualizing his personality.[164] Furthermore, Heinrich Carl Schimmelmann was not the owner of the biggest plantations in the Danish West Indies according to a map. There were also bigger plantations and if they would have been worked, they might have had more slaves. Along with this speculation the hobby historian urged me again to be careful with what I was saying about Schimmelmann as a colonialist, slave owner and slave trader. [165]

“One must not write that Schimmelmann lived from his income from the plantations. He also had other incomes. Just his assets in Kopenhagen and Hamburg were worth more than his plantations and the sugar plant.” [166]

On September 3, 2020 the education, cultural affairs and sports committee had its sitting in Ahrensburg. More citizens than usual showed up and already their contributions in the questioning period made evident why they had come. They were interested in TOP 7 of the agenda: “Recognitions and designations in the public realm”.[167]

A resident of the Schimmelmannstraße called it unbearable to live in a street carrying a name of a slave trader. Following these statements, a heated debate unfolded in the committee and it seemed that the members would reject the proposal to call in a new committee which should check the town’s street names because this committee was to expensive. Especially conservative parties claimed that this committee would cost too much and used the coronavirus pandemic as a reason why the town could not afford to at least think about some street names. They did not talk about the Schimmelmannstraße in particular and forming the committee would not even mean to really change any names. Finally, the mayor got angry and threatened the members that protests against Bismarck monuments in Hamburg could easily bring chaos and destruction to the town as Hamburg is very close to Ahrensburg. He urged the members to accept the proposal and thus starting a dialogue focussing on facts and not on emotions as he claimed the current debate was very emotionally driven. Historians shall look at people like H.C. Schimmelmann and only after one year it might be determined whether it would still be appropriate to name a street after the family Schimmelmann. Finally, the members of the committee accepted the proposal. However, the proposal still needs approval of other committees.

Looking at letters to the editors in newspapers in Ahrensburg, the white, male, affluent and old majority in Ahrensburg are very unhappy with this decision and paying money for new street signs or even finding an appropriate name will remain a highly debated and controversial issue.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the interviews show that the town of Ahrensburg is starting to deal with its colonial past. But surprisingly they do not call it colonialism. It does not appear to be publicly known or interesting that several generations of the Schimmelmann family were actively engaged in colonialism. The debate focusses on one person: Heinrich Carl Schimmelmann. This is also due to historians who have exaggerated this “great man’s” meaning. Of course, H.C. Schimmelmann laid the foundation of the family’s wealth and is publicly known as a slave trader. But his descendants lived of his fortune and continued to own plantations and slaves as well as he did. And even if the plantations did not provide the family with a steady income this did not free the slaves, this did not stop slavery and colonialism.

Public conscience in Ahrensburg surprisingly only focusses on “slavery” which appears to be not connected to “colonialism” for some people. It becomes a minor issue how money flowed to Ahrensburg from colonial trade. Even people that are professionally dealing with Ahrensburg’s history like museum staff, politicians or other professionals only know about Heinrich Carl Schimmelmann and his slave trade, while they ignore the structural relations of Ahrensburg’s past and colonialism. Debates on colonial legacy e. g. the funding of buildings like the Marstall have not yet been held and it seems very unlikely that a monument for the atrocities of slavery administered in Ahrensburg will be constructed in the near future.

Nonetheless, my research project has shown that the majority of the town’s population know very little about the history of “their” castle, its former inhabitants and the town’s history in general. While buildings from the Schimmelmann era like Marstall, castle and church are an integral part of the town’s historical conscience and cultural life, everyday life stays untouched of issues like colonial traces in the town. However, the importance of these buildings might offer a chance for the town’s population to learn more about them and thus evolving a conscience for Ahrensburg’s colonial past. As Ahrensburg is an important memorial site of German colonialism.

References

[1] Jürgen Zimmerer, “Kolonialismus Und Kollektive Identität: Erinnerungsorte Der Deutschen Kolonialgeschichte,” in Kein Platz an der Sonne : Erinnerungsorte der deutschen Kolonialgeschichte, ed. Jürgen Zimmerer, 9–37 (Frankfurt am Main [u.a.]: Campus-Verl., 2013), 10–11.

[2] Serge Grunzinski, “How to Be a Global Historian,” PublicBooks, September 15, 2016, https://www.publicbooks.org/how-to-be-a-global-historian/ (accessed May 5, 2020).

[3] Stadt Ahrensburg, Ahrensburg in Zahlen (January 17, 2019), https://www.ahrensburg.de/B%C3%BCrger-Stadt/Stadtportrait/Ahrensburg-in-Zahlen (accessed September 7, 2020).

[4] Cf. Karin Gröwer, “Ahrensburg – eine junge Stadt wird 60,” in Ahrensburg: Eine junge Stadt wird 60, ed. Karin Gröwer, Christa Reichardt and Günter Weise, 7–10 (Husum: Husum Druck- und Verlagsges, 2009), 9.

[5] Harald Dzubilla, “Ohne Schloss Ist Ahrensburg Gar Nichts!,”, https://szene-ahrensburg.de/static/2013/08/ohne-schloss-ist-ahrensburg-nichts/ (accessed July 7, 2020).

[6] Cf. Jürgen Zimmerer, “Kolonialismus und kollektive Identität,” in Kein Platz an der Sonne : Erinnerungsorte der deutschen Kolonialgeschichte, 10–11.

[7] Cf. Angela Behrens, Das Adlige Gut Ahrensburg von 1715 bis 1867: Gutsherrschaft und Agrarreformen, Stormarner Hefte Nr. 23 (Neumünster: Wachholtz, 2006); Zugl.: Hamburg, Univ., FB Sozialwiss., Diss., 2004, 14.

[8] Cf. Tatjana Ceynowa, “Die Nachfolgenden Genrationen: Bewegte Zeitläufe,” in Schloss Ahrensburg: Ein Kleinod in Schleswig-Holstein mit über 400jähriger Geschichte, ed. Stiftung Schloss Ahrensburg, 40–3 (2019), 43.

[9] Cf. Tatjana Ceynowa, “Die Trägerschaft Des Schlosses: Eine Private Stiftung,” in Schloss Ahrensburg: Ein Kleinod in Schleswig-Holstein mit über 400jähriger Geschichte, ed. Stiftung Schloss Ahrensburg, 128–9 (2019), 128–29.

[10] Cf. Tatjana Ceynowa, “Ein Schloss Für Ganz Besondere Tage: Es Gibt Viel Zu Erleben,” in Schloss Ahrensburg: Ein Kleinod in Schleswig-Holstein mit über 400jähriger Geschichte, ed. Stiftung Schloss Ahrensburg, 124–7 (2019), 124–27.

[11] Cf. Marstall Ahrensburg. “Tagen und Feiern”. https://www.marstall-ahrensburg.de/tagen-und-feiern/ (accessed September 6, 2020).

[12] Cf. Behrens, Angela „Designation of Schimmelmanstraße, via e-mail.

[13] Cf. Susanne Link, “Ahrensburg: Rassismus-Debatte Geht in Die Nächste Runde,” shz.de, September 4, 2020, https://www.shz.de/lokales/stormarner-tageblatt/rassismus-debatte-geht-in-die-naechste-runde-id29518722.html (accessed September 6, 2020).

[14] Tear This Down, https://www.tearthisdown.com/de/ (accessed September 9, 2020).

[15] Cf. Tatjana Ceynowa, “Die nachfolgenden Genrationen,” in Schloss Ahrensburg, 43.

[16] Behrens, Das Adlige Gut Ahrensburg von 1715 bis 1867, 18.

[17] Martin Krieger, “Heinrich Carl Von Schimmelmann,” in Kein Platz an der Sonne : Erinnerungsorte der deutschen Kolonialgeschichte, ed. Jürgen Zimmerer, 311–22 (Frankfurt am Main [u.a.]: Campus-Verl., 2013), 314.

[18] Cf. Christian Degn, Die Schimmelmanns im atlantischen Dreieckshandel: Gewinn u. Gewissen, 3. unveränderte Auflage (Neumünster: Wachholtz, 2000 [1974]), 94.

[19]„Schon 1767, vier Jahre nach dem Kauf, warfen Plantagen und Raffinerie einen Gewinn von 54 298 Reichstalern ab.“ Ruth Hoffmann, “Brutales Kolonialgeschäft Im 18. Jahrhundert: Ein Deutscher Kaufmann Und Sklavenhändler,” DER SPIEGEL, June 12, 2020, https://www.spiegel.de/geschichte/heinrich-carl-schimmelmann-ein-deutscher-kaufmann-und-sklavenhaendler-a-00000000-0002-0001-0000-000161977582 (accessed June 12, 2020).

[20] Cf. Degn, Die Schimmelmanns im atlantischen Dreieckshandel, 67; Cf. Martin Krieger, “Heinrich Carl von Schimmelmann,” in Kein Platz an der Sonne : Erinnerungsorte der deutschen Kolonialgeschichte, 320.

[21] Cf. Martin Krieger, “Heinrich Carl Von Schimmelmann,” in Kein Platz an der Sonne : Erinnerungsorte der deutschen Kolonialgeschichte, ed. Jürgen Zimmerer, 311–22 (Frankfurt am Main [u.a.]: Campus-Verl., 2013), 315.

[22] Behrens, Das Adlige Gut Ahrensburg von 1715 bis 1867, 181–84.

[23] Cf. „Bausachen“ LASH Abt. 127.3, Nr. 647.

[24] Cf. Behrens, Das Adlige Gut Ahrensburg von 1715 bis 1867, 358.

[25] Cf. Hoffmann, “Brutales Kolonialgeschäft im 18. Jahrhundert: Ein deutscher Kaufmann und Sklavenhändler,”; Friederike Gräff, “Der Größte Menschenhändler Seiner Zeit,” taz. Die tageszeitung (8.12.2006); Elisabeth Knoblauch, “Aus Der Heimat Entführt, Um Europa Zu Amüsieren: Auch Deutschland Trägt Schuld an Kolonialverbrechen. Mit Hamburg Hat Sich Erstmals Eine Stadt Dafür Entschuldigt,” Die Zeit 73, no. 51 (2018).

[26] BBC News, “Edward Colston Statue: Man Held over Criminal Damage,” BBC News, July 1, 2020, https://www.bbc.com/news/uk-england-bristol-53258535 (accessed September 8, 2020).

[27] Translated by the author. Jürgen Zimmerer, “Solange Die Denkmäler Ungebrochen Stehen, Wird Dieses Weltbild Weiter Verherrlicht,” Deutschlandfunk Nova, June 8, 2020, min. 2:17-2:36, https://www.deutschlandfunknova.de/beitrag/rassismus-und-kolonialismus-umstrittene-denkmaeler (accessed June 9, 2020). In another interview Jürgen Zimmerer said: “Nicht nur gab es die Schimmelmanns und Colstons und Wissmanns und wie sie alle heißen. Sondern diese Gesellschaft, unsere Vorläufergesellschaft, hat die sogar einmal gefeiert.” Jürgen Zimmerer, “Kolonialerbe in Hamburg: Wie soll damit umgegangen werden?,” NDR info, September 8, 2020, https://www.ndr.de/kultur/Kolonialerbe-in-Hamburg-Wie-soll-damit-umgegangen-werden,kolonialerbe104.html (accessed September 8, 2020).

[28] Cf. Degn, Die Schimmelmanns im atlantischen Dreieckshandel, 199.

[29] Cf. Erik Gøbel, The Danish Slave Trade and Its Abolition, Studies in global slavery volume 2 (Leiden, Boston: Brill, 2016), 75.

[30] Behrens, Das Adlige Gut Ahrensburg von 1715 bis 1867, 175.

[31] Degn, Die Schimmelmanns im atlantischen Dreieckshandel, 4.

[32] These islands were sold by Denmark to the US in 1917 and are known as the US-Virgin Islands today (Cf. ibid., 521; Erik Gøbel, “Colonial Empires,” in The Cambridge history of Scandinavia: Vol. 2: 1520-1870, ed. Erkki I. Kouri, Jens E. Olesen and Knut Helle, 279–309 (2016), 306).

[33] Degn, Die Schimmelmanns im atlantischen Dreieckshandel, 67.

[34] Gøbel, The Danish slave trade and its abolition, 75.

[35] Cf. Martin Krieger, “Heinrich Carl von Schimmelmann,” in Kein Platz an der Sonne : Erinnerungsorte der deutschen Kolonialgeschichte, 316.

[36] Cf. Degn, Die Schimmelmanns im atlantischen Dreieckshandel, 79.

[37] Cf. ibid., 77.

[38] Cf. Klaus Weber, “Deutschland, Der Atlantische Sklavenhandel Und Die Plantagenwirtschaft Der Neuen Welt (15. Bis 19. Jahrhundert),” Journal of Modern European History 7, no. 1 (2009): 51.

[39] Cf ibid., 50–51; Cf. Gøbel, The Danish slave trade and its abolition, 75.

[40] Cf. Degn, Die Schimmelmanns im atlantischen Dreieckshandel, 166–67; 75Gøbel, The Danish slave trade and its abolition.

[41] Cf. Gøbel, The Danish slave trade and its abolition, 75.

[42] The trust was called “Fideikommiss”. It was a common way for noble people in Germany to combine their inheritance in this kind of trust to ensure that it stayed in the hands of the family (cf. Behrens, Das Adlige Gut Ahrensburg von 1715 bis 1867, 177).

[43] Gøbel, The Danish slave trade and its abolition, 79.

[44] Cf. Bestätigung der Erlöschung der Eigentümerschaft des Fideikommisses, LASH Abt. 350 Nr. 3451, Bl. 72.

[45] Degn, Die Schimmelmanns im atlantischen Dreieckshandel, 512.

[46] Gøbel, The Danish slave trade and its abolition, 56.

[47] Anonymus ll. 188-193.

[48] „Allerdings konnte Carl Schimmelmann selbst zu jener Zeit [Napoleonischen Kriege] auf die Geldeinkünfte aus dem Geldfideikommiss rechnen. Zu dem Geldfideikommiss gehörten neben den Plantagen auf den Zuckerinseln einige staatliche Anleihen, die Gewehrfabrik in Hellebek, das Kopenhagener Palais in der Bredgarde sowie die Zuckerfabrik in Kopenhagen. Im Jahr 1809 erhielt er allein 6.000 Reichstaler reguläre Fideikommisszinsen.“ Behrens, Das Adlige Gut Ahrensburg von 1715 bis 1867, 305–6.

[49] Ibid., 306.

[50] Ibid., 308. However, the counts von Baudissin also received some revenues from the trust as one of H.C. Schimmelmann’s daughters had married to a count von Baudissin.

[51] Cf. Degn, Die Schimmelmanns im atlantischen Dreieckshandel, 406.

[52] Behrens, Das Adlige Gut Ahrensburg von 1715 bis 1867, 306.

[53] Cf. ibid., 308–309 & 361.

[54] Ibid., 364–65.

[55] Sonja Vogt, “Schimmelmann Und Die Sklaven,” in Schloss Ahrensburg: Ein Kleinod in Schleswig-Holstein mit über 400jähriger Geschichte, ed. Stiftung Schloss Ahrensburg, 30–1 (2019), 31.

[56] Cf. Erik Gøbel, “Colonial empires,” in The Cambridge history of Scandinavia, 304.

[57] Cf. ibid.

[58] Cf. Weber, “Deutschland, der atlantische Sklavenhandel und die Plantagenwirtschaft der Neuen Welt (15. bis 19. Jahrhundert),”: 51.

[59] Cf. Degn, Die Schimmelmanns im atlantischen Dreieckshandel, 295.

[60] Cf. Svend E. Green-Pedersen, “An Entrepreneurial History,” Scandinavian economic history review 24, no. 1 (1976): 67.

[61] Cf. Degn, Die Schimmelmanns im atlantischen Dreieckshandel, 295.

[62] Cf. ibid., 290.

[63] Cf. ibid., 108–10.

[64] Ibid., 113.

[65] Cf. ibid., 114–15.

[66] Cf. ibid., 80–81.

[67] Cf. Henning J. H. Eicke, “Beschreibung Des Guts Ahrensburg: Herausgegeben Vom Historischen Arbeitskreis Ahrensburg,” Historische Blätter, no. 14 (1991): 1.

[68] Ibid., 41–42.

[69] Cf. ibid., 42–49.

[70] Christa Reichardt [Georg Philipp Schmidt], Die Schimmelmanns, Ahrensburger Heft 1 (1985), 3.

[71] “Meißner Porzellan”.

[72] „abgewirthschaftet“ Hans-Hinrich Rahlf and Ernst Ziese, Geschichte Ahrensburgs – Nach Authentischen Quellen Und Handschriftlichen Akten Bearbeitet, Anhang Enthaltend: Sagen, Märchen Und Erzählungen Aus Dem Gute Ahrensburg Und Dem Kreise Stormarn. (Ahrensburg: Neudruck Buchhandlung Otte, o. D., 1882), 134.

[73] Cf. Martin Krieger, “Heinrich Carl von Schimmelmann,” in Kein Platz an der Sonne : Erinnerungsorte der deutschen Kolonialgeschichte, 313.

[74] „Legendenbildung“ Hans Schadendorff, “Die Wansbeker Grabkapelle: Leben, Tod Und Bestattung Des Schatzmeister Graf Heinrich Carl Von Schimmelmann Und Seiner Gemahlin Caroline Tugendreich Von Schimmelmann Geb. Friedeborn,” Nordelbingen 11 (1935): 187. Similar publications at this time include Peter Hirschfeld, “Die “Schatzmeister-Rechnungen” Des Ahrensburger Schlossarchivs Als Kulturgeschichtliche Quelle,” Nordelbingen 15 (1939); Peter Hirschfeld, “Ernst Schimmelmanns Reise Nach England Und Frankreich 1766– 1767,” Personalhistorisk Tidsskrift (1938); Hans Schadendorff, “Schloß Ahrensburg Und Dorf Woldenhorn – Baugeschichte Ahrensburgs in Der Rantzauschen Und Schimmelmannschen Zeit,” Nordelbingen 12 (1936).

[75] There is only the word “sugar plantations” in a list of Schimmelmann’s other assets. Cf. Schadendorff, “Die Wansbeker Grabkapelle,”: 192.

[76] Cf. Martin Krieger, “Heinrich Carl von Schimmelmann,” in Kein Platz an der Sonne : Erinnerungsorte der deutschen Kolonialgeschichte, 313.

[77] Degn, Die Schimmelmanns im atlantischen Dreieckshandel.

[78] Cf. Martin Krieger, “Heinrich Carl von Schimmelmann,” in Kein Platz an der Sonne : Erinnerungsorte der deutschen Kolonialgeschichte, 317.

[79] Degn, Die Schimmelmanns im atlantischen Dreieckshandel, 538.

[80] Cf. Martin Krieger, “Heinrich Carl von Schimmelmann,” in Kein Platz an der Sonne : Erinnerungsorte der deutschen Kolonialgeschichte, 313.

[81] Cf. the website of the local historical association for contact information and the work they are doing, http://www.historischer-arbeitskreis-ahrensburg.de/

[82] Christa Reichardt, Hermann-Jochen Lange, Reinhard Specht, Die Große Straße in Ahrenburg Gestern – Heute – Morgen, Ahrensburger Heft 2 (1986); Helga d. Cuveland, Schloss Ahrensburg und die Gartenkunst, Stormarner Hefte Nr. 18 (Neumünster: Wachholtz, 1994); Dieter Lohmeier, Frauke Lühning and Wolfgang Teuchert, “Im Blickpunkt: Schloß Ahrensburg: Vorträge Zur 400-Jahrfeier 1595-1995,” Historische Blätter, no. 17 (1996); Christa Reichardt, Wolfgang D. Herzfeld and Wilfried Pioch, eds., 400 Jahre Schloß und Kirche Ahrensburg: Grafen, Lehrer und Pastoren (Husum: Husum, 1995); Christa (v.) Reichardt, “Die Entstehung Des Ahrensburger Schlosses; Die Leibeigenschaft Im Gutsbezirk Ahrensburg,” Historische Blätter, 1-2 (2002); Neuauflage der historischen Blätter Nr. 1-5; Wera Meyer, Post in Ahrensburg, Ahrensburger Heft 3 (1987); Stadt Ahrensburg, Ahrensburg (o. D.); Karin Gröwer, Christa Reichardt and Günter Weise, eds., Ahrensburg: Eine junge Stadt wird 60 (Husum: Husum Druck- und Verlagsges, 2009); Gemeinschaftsarbeit der Grundschule am Aalfang, Als Ahrensburg Noch Woldenhorn Hieß.

[83] Arne Wolter, Ahrensburg im Wandel in alten und neuen Bildern (Hamburg: Medien-Verl. Schubert, 1992), 26.

[84] Cf. Christa Reichardt, “Starke Wurzeln: Klostervogtei, Gutsdorf, Landgemeinde,” in Ahrensburg: Eine junge Stadt wird 60, ed. Karin Gröwer, Christa Reichardt and Günter Weise, 11–9 (Husum: Husum Druck- und Verlagsges, 2009), 15.

[85] Behrens, Das Adlige Gut Ahrensburg von 1715 bis 1867.

[86] Jürgen Zimmerer, ed., Kein Platz an Der Sonne : Erinnerungsorte Der Deutschen Kolonialgeschichte (Frankfurt am Main [u.a.]: Campus-Verl., 2013).

[87] „Erinnerungsorte”

[88] Sonja Vogt, “Schimmelmann und die Sklaven,” in Schloss Ahrensburg.

[89] Ibid., 30.

[90] Cf. ibid.

[91] Ibid., 31.

[92] Cf. ibid.

[93] Cf. Erich Maletzke, Schatzmeister des Königs: Ein dokumentarischer Roman (Neumünster: Wachholtz, 2009); Hannelore Neugebauer, Das Geheimnis Der Grauen Pantoffeln: Eine Märchenhafte Erzählung Mit Wahren Geschichten Über Das Schloß Ahrensburg (Verein Schloß Ahrensburg e.V.).

[94] Translated by the author. Interview Christian Schubbert, ll. 201-203.

[95] First name classified upon request of interviewee.

[96] Janina Dietrich and Christian Thiessen, “Ahrensburger Wollen Alte Straßennamen Prüfen: Schulleiter Kritisiert Geplante Schilder Für Alfred Rust Saal Und Löst Debatte Aus. Grüne Wollen Arbeitsgruppe Zu Dem Thema Einberufen,” Hamburger Abendblatt, July 10, 2020, https://www.abendblatt.de/region/stormarn/article229483650/Ahrensburger-wollen-alte-Strassennamen-pruefen.html (accessed August 29, 2020); Anonymus, “Ahrensburger Grüne Schieben Debatte Über Bedenkliche Straßennamen an,” Lübecker Nachrichten, July 11, 2020, https://www.ln-online.de/Lokales/Stormarn/Ahrensburger-Gruene-schieben-Debatte-ueber-bedenkliche-Strassennamen-an (accessed July 21, 2020); Cordula Poggensee and Finn Fischer, “Rassismusdebatte in SH : Ahrensburger Grüne Fordern: Historische Straßennamen Neu Bewerten,” shz.de, July 8, 2020, https://www.shz.de/lokales/stormarner-tageblatt/ahrensburger-gruene-fordern-historische-strassennamen-neu-bewerten-id28904557.html (accessed July 14, 2020).

[97] (tm/ksb)., “In Stormarn Gibt Es Gesprächsbedarf: Landtagsdebatte Zur Kolonialgeschichte,” Markt, July 1, 2020, http://epaper.lokale-wochenzeitungen.de/mabmah/311/ (accessed July 10, 2020); Christian Schubbert-von Hobe, “Straßennamen: Antrag an Den Bildungs-, Kultur- Und Sportausschuss,” (02.07.2020), https://www.gruene-ahrensburg.de/userspace/SH/ov_ahrensburg/Dateien/Antrag_Strassennamen.pdf (accessed August 29, 2020).

[98] Translated by the author. Martin Habersaat, “Rede Zu: Aufarbeitung Der Europäischen Und Deutschen Kolonialgeschichte in Schleswig-Holstein,” Landtag Schleswig Holstein, June 17, 2020, https://www.martinhabersaat.de/2020/06/19/wir-sind-noch-nicht-fertig/ (accessed September 25, 2020) Habersaat, “Rede zu: Aufarbeitung der Europäischen und Deutschen Kolonialgeschichte in Schleswig-Holstein,”.

[99] Cf. Freundeskreis Schloss Ahrensburg e.V., https://freundeskreis-schloss-ahrensburg.de/# (accessed August 25, 2020).

[100] Translated by the author. Interview Dieter Blank ll. 53-57 (Appendix I).

[101] Ibid. ll. 96-98.

[102] Ibid. ll. 13-16.

[103] Ibid. ll. 35-44.

[104] Cf. Martin Krieger, “Heinrich Carl von Schimmelmann,” in Kein Platz an der Sonne : Erinnerungsorte der deutschen Kolonialgeschichte, 319.

[105] Translated by the author. Interview Dieter Blank ll. 41-43.

[106] Ibid. ll. 44-46; ll. 60-62.

[107] For the controversial debate on the Schimmelmann bust see Hamburger Morgenpost, “SKLAVENHÄNDLER SCHIMMELMANN: Das Denkmal Kommt Weg,” MOPO.de, May 13, 2008, https://www.mopo.de/sklavenhaendler-schimmelmann-das-denkmal-kommt-weg-19581220 (accessed September 9, 2020).

[108] Cf. Martin Krieger, “Heinrich Carl von Schimmelmann,” in Kein Platz an der Sonne : Erinnerungsorte der deutschen Kolonialgeschichte, 319.

[109] Cf. https://www.szene-ahrensburg.de/ (accessed August 29, 2020)

[110] Translated by the author. Interview Harald Dzubilla ll. 38-40.

[111] Translated by the author. Ibid. ll. 84-86.

[112] Translated by autor. Ibid. ll. 63-69.

[113] Degn, Die Schimmelmanns im atlantischen Dreieckshandel.

[114] Translated by the author. Interview Harald Dzubilla ll. 243-245.

[115] Ibid. ll. 78-81.

[116] Ibid. ll. 172-175.

[117] Translated by the author. Ibid. ll. 181-184.

[118] Interview von Baudissin l. 92.

[119] Degn, Die Schimmelmanns im atlantischen Dreieckshandel.

[120] Interview von Baudissin, ll. 26-36.

[121] Ibid. l. 47 & ll. 68-70.

[122] Translated by the author. Ibid. ll. 43-47.

[123] Name changed upon request of interviewee.

[124] Interview Bjorn Nielsen, ll. 26-29.

[125] For the mentioned article on Wikipedia visit https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Heinrich_Carl_von_Schimmelmann (accessed August 30, 2020).

[126] Translated by the author. Passage modified by interviewee. Interview Bjorn Nielsen ll. 58-65.

[127] Ibid. ll. 73-74.

[128] Ibid. ll. 88-93.

[129] Interview Ilse Groot, ll. 9-12.

[130] Ibid. ll. 43-44.

[131] Interview Benjamin Groot, ll. 126-134.

[132] Name changed upon request of interviewee.

[133] Translated by the author. Interview Dr. Anastasija Zwetkowa, ll. 113-116.

[134] Ibid. ll. 144-147.

[135] Ibid. ll. 163-166.

[136] Ibid. ll. 210-216.

[137] Translated by the author. Ibid. ll. 342-344.

[138] Ibid. ll. 60-63.

[139] Translated by the author. Ibid. ll. 329-341.

[140] Translated by the author. Ibid. ll. 388-391.

[141] Ibid. ll. 490-491.

[142] Ibid. ll. 249-257.

[143] Ibid. ll. 402-405.

[144] Ibid. ll. 393-406.

[145] Interview Lara Marie Haude, ll. 3-4.

[146] (tm/ksb)., “In Stormarn gibt es Gesprächsbedarf”.

[147] Translated by the author. Interview Tobias von Pein, ll. 9-16.

[148] Ibid. ll. 142-144.

[149] Translated by the author. Ibid. ll. 49-60.