This was a summer that burned. A summer burned into our collective consciousness, as a novel virus blazed across international borders, snatching millions of lives with its still kindling flames. The COVID-19 pandemic not only ignited a threatening instability in the biomedical, economic and political spheres, but additionally inflamed preexisting systemic inequalities that are endemic throughout the globe. Yet the enduring flames of COVID-19 was not the only crisis in this planetary conflagration. A series of fatal shootings of unarmed Black individuals by police officers in the United States sparked an international movement advocating to dismantle systemic racism and inequalities and a broader collective discussion of how to alleviate the legacies and persistence of racial injustice — rekindling the Black Lives Matter movement at an unprecedented scale. The streets burned with cries of anger and justice. The American economic, political and medical systems burned under the omnipresent weight of instability, uncertainty and infrastructural weaknesses. And we watched as a microscopic virus hijacked anatomies and stripped breaths away, often in the very bodies that have been historically invisible and repressed — we watched as our bodies burned.

BACKGROUND

The New York City metro area was one of the first regions in the United States to face an outbreak of COVID-19 in early March 2020. As case counts rapidly escalated and city hospitals were overwhelmed by the influx of critically ill patients — during a time where the transmission, prognosis and treatments for this novel disease were still scientifically uncertain — New York State Governor Andrew Cuomo issued a lockdown for New York State on March 20, 2020.[1]

Coronavirus cases throughout the city quickly rose, leading to the peak of the pandemic in the New York area in early April. The city recorded the highest 7-day rolling average for new coronavirus cases on April 8, with a total average of 5,305 new coronavirus cases being documented each day (which excludes those who contracted the virus and were not tested, particularly those who were asymptomatic).[2] Statistically speaking, April 6 was a groundbreaking day for the coronavirus in New York City, reaching a record number of confirmed cases and hospitalizations — the city documented 6,377 new cases and 1,721 hospitalizations — many of whom were critically ill, culminating in an overburdened healthcare system. The next day, on April 7, a record 597 individual deaths were recorded.

An ICU worker at a major hospital in Manhattan discussed the emotional toll of the rapid and unexpected cascades of death. “It was just a lot of death…you’re just made very aware of the reality of dying.”

Much of the media coverage and both academic and public discourse focused on the coronavirus itself— its changing infection and mortality rates, the overwhelming of hospitals and critical care facilities, and developments in potential drugs and vaccines. Yet, the pandemic has not only afflicted those healthcare settings that directly treat coronavirus patients, but has also had more indirect effects on sectors of healthcare not directly focused on treating patients with COVID-19, shaping people’s experience in primary care settings. Outpatient care, and especially primary care, have a critical role in healthcare delivery and are instrumental in monitoring and treating potentially serious chronic conditions.[4] The COVID-19 pandemic dramatically changed outpatient care delivery in the United States, as many facilities shifted to telemedicine instead of in-person visits for applicable conditions and many patients grew hesitant to enter a healthcare setting during a raging pandemic. In fact, by early April, visits to outpatient care facilities in regions with high COVID-19 activity (like New York City) had decreased by 65 percent from early February and 57 percent nationally. While visits began to increase at the end of April, by mid-June, outpatient visits in regions that experienced significant COVID-19 case counts in March and April were still 17 percent fewer in New York, and 11 percent fewer nationally, than they were in early February.[5]

Evidently, COVID-19 has seemed to reach nearly every corner of society, attesting to the multidimensionality and complexity of pandemics. But, it is important to recognize that the COVID-19 pandemic was not a universal affliction, as it had disproportionate impacts on traditionally marginalized communities, such as Blacks and Latinos, as well as low-income households.

Data released by the New York City health department revealed significant disparities between white neighborhoods and predominantly Black and Latino, low-income neighborhoods, which experienced some of the highest death rates in the city. According to the published data, in the predominantly wealthy and white enclave of Gramercy Park in Manhattan, there was a COVID-19 death rate of 31 per 100,000 residents, while in Far Rockaway — a neighborhood on the outskirts of Queens that is more than 40 percent black and 25 percent Latino — the death rate was 444 deaths per 100,000 residents, which is almost 15 times greater than that of Gramercy Park. [6] Overall, in early April, the confirmed COVID-19 death rate in New York City for Hispanic[7] people was 22 people per 100,000 and 20 per 100,000 for Black people. Yet the COVID-19 death rate for white residents was nearly half that of Black and Latinos, with a recorded rate of 10 per 100,000.[8]

Data from New York City in early April.

A glaring discrepancy emerges here, where Blacks and Latinos have nearly twice the death rate than whites from coronavirus (as well as living in areas disproportionately afflicted by the virus). Social scientists and community and government leaders have weighed in on this disconnect, noting that low income people of color traditionally have more undertreated chronic health conditions (in comparison to higher income whites) that can increase their chances of becoming severely ill and dying from the coronavirus. Black and Latino people are also disproportionately employed in lower wage, essential worker jobs that place them in higher risk environments for contracting the virus. In fact, one report from the city comptroller’s office found that 75 percent of frontline workers (grocery store workers, transit workers, janitors and childcare staff) are minorities.[9]

While these statistics can be illuminative of the impact and inequalities of the coronavirus, this data-driven research methodology still has limitations in understanding the complexities of the coronavirus pandemic. Numerical data can provide generalized insights about these social and scientific phenomena, often through a more macro-scale approach of documenting trends among larger populations. However, these data points are often not fully reflective of the whole story — namely, struggling to capture the critical role of personal narratives and individual perspectives on a pandemic that has so dramatically changed people’s lives in unique and non-universal ways.

Oral history can help fill these methodological gaps, as it encapsulates the complexities and personal perspectives of people’s experiences, creating a shared historical agency between the researcher and subject. In the media, academic research and even in public discourse, the coronavirus has frequently been discussed through a reductionist and depersonalized lens — the rising case counts and deaths, record-high unemployment claims and job losses, the proportion of students returning — presenting numerical figures and statistics as if they are reflective of wide swaths of the population’s experiences. Oral history helps to complicate and deepen perceptions of the pandemic, integrating individual perspectives and most importantly genuine voices into the national conversation. This is particularly important for marginalized communities — those who historically have not had the opportunity to have their voices amplified and histories heard due to legacies of structural violence, oppression and inequality. While news reports blasted shocking statistics of the detrimental effects of coronavirus on Blacks and Latinos, citing their disproportionate statistics, there was a missing humanistic and complex ethnographic element. How were the violent forces of the epidemic experienced by individual people? Similarly, as healthcare networks documented the changes in visits and procedures conducted, a question of why and how appears as well. Why are these behaviors changing? How do people individually interpret the epidemic phenomena and by what rationales do these translate into new perspectives and interactions with healthcare? Well, let’s let them speak.

THE PROJECT

Through the History Dialogues project — an initiative facilitated by the Global History Lab at Princeton University focused on teaching oral history research methods to learners around the world — I interviewed several people from Afro-Caribbean communities in the New York City area, exploring how their overall perception and willingness to access healthcare has been influenced by the coronavirus. These communities have been disproportionately affected both economically and medically. As one young man I interviewed said, “I feel everybody at this point in my immediate circle knows somebody that has passed from this virus. It’s been an eye opener for people in my community.” [10]

Considering minority communities’ heightened affliction with the virus, as well as a documented national decrease in primary care visits (which are often even more essential in communities of color that have historically had higher rates of chronic conditions like diabetes, asthma, and hypertension), a question emerges of how are these communities engaging with healthcare services, particularly outpatient care?

How has the COVID-19 pandemic influenced perceptions and willingness to access healthcare services, particularly primary care, in Afro-Caribbean communities in the New York city area?

Oral history provides a unique opportunity to grasp the intricacies of why and how people in Afro-Caribbean communities interact with healthcare services, as it creates a forum to express their hesitancies, uncertainties and nuanced prior experiences. Among the interviewees, there still were some lingering hesitancies on visiting hospital settings, but overall, there was not a major resistance to visit the outpatient care setting due to the infection control measures in place in many outpatient settings.

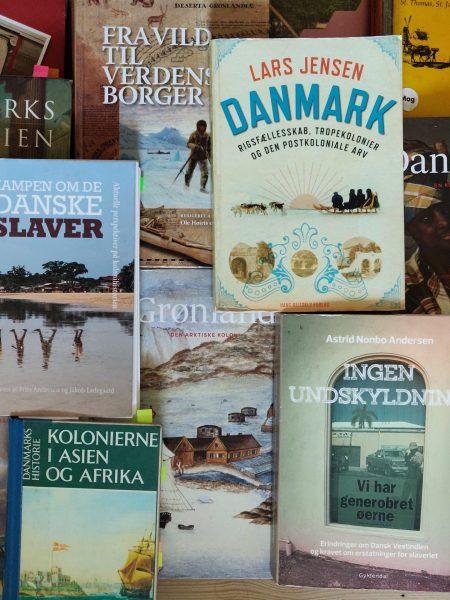

But, in examining the relationship between the healthcare system and this historically low-resource community, it is important to recognize that the pervasive socioeconomic inequalities, discrimination and poorer access to high-quality healthcare do not emerge out of a vacuum. These inequities have deeply ingrained historical roots that extend centuries beyond the beginning of the coronavirus. Much of the societal and media discourse surrounding the coronavirus has cast it within a temporal binary: life prior to COVID-19 and post-COVID-19. Yet, through engaging with these interviewees about their perspectives and history with healthcare systems, a more long standing distrust became apparent, emanating from centuries of medical racism and subpar medical care access and quality concentrated in Black areas, often culminating in health disparities still present today. In this instance, the “COVID-19 binary” does not apply, as hesitancy and mistrust surrounding healthcare systems have been endemic in Afro-Caribbean communities, but the medical crisis posed by the COVID-19 pandemic has exacerbated these pre-existing disconnects, further fracturing an already broken relationship.

PERSPECTIVES ON ACCESSING HEALTHCARE

During the peak of the coronavirus pandemic in New York City, the healthcare setting, especially the hospital, became a venue for anxiety and uncertainty. Robert, a middle-aged man living in Canarsie, Brooklyn, discussed his anxiety when entering the hospital in April for an outpatient procedure. “It was scary,” he said. “You just never know. Touching things and sitting in the chair…it’s like a parasite. Because you don’t even know how you can get it. It was scary.”[11] For many, the uncertainty of the coronavirus itself at the time — its myriad potential routes of transmission — became a major factor in cultivating a fear of the physical environment of healthcare.

Robert continued, saying that “you’re even thinking about the instruments they’re going to use. That was really one of my concerns. You don’t know who just had a [procedure] and maybe they may have the virus. Maybe they sterilize and whatever, but at the time they don’t even know if sterilization could kill the germs because we wasn’t even knowledgeable about what the virus was at the time.”[12] Robert’s sentiments reflect a prevailing skepticism about the medical environment, influenced by the contemporaneous scientific uncertainties and a healthcare system that was flailing under the surge of the coronavirus. While scientific authorities at the time may have provided convincing evidence that countered some of these prevalent fears, throughout the interviews there was a persistent uncertainty around the hospital setting, which is especially important to acknowledge among a population that has been historically underserved by medical institutions.

Sharon, a middle-aged woman from East Flatbush, Brooklyn who immigrated from the small Caribbean island of St. Vincent in the 1980s, expressed a similar uncertainty when asked if she would be willing to go to a hospital, if needed. With an assertive tone, she said “I don’t think I would want to go. I would try all the different home remedies first before I go in anybody hospital right now. I don’t think the hospital is a safe place to go right now…You don’t know who has what.” [13] After weeks of sustained case counts, the hospital setting has become associated with the most critically ill and often, a place of death — a place representing the dramatic uncertainties of the coronavirus.

Overall, the interviewees expressed more hesitancy to enter a hospital than an outpatient care setting during the period when these interviews were conducted in August 2020, but there was still a lingering hesitancy among some to visit their primary care doctor. When asked about visiting their primary care provider, a common response consisted of “if I have to” — often reflecting a willingness to go to their provider if a medical problem arose, despite a persisting anxiety about the healthcare setting.

Robert encapsulated this pattern among interviewees, explaining that “I would go if need be. I have no other choice. But the way I see it, it’s like going into a battlefield, like an army, you don’t know what’s gonna happen. You still don’t know what the outcome is gonna be. Even though you’re prepared, it’s like going in a battlefield.” [14] In some ways, the early scientific unknowns of this novel virus bleeds into a more popular hesitancy regarding the medical system.

Darryl, a 28-year-old man from Brooklyn, also reiterated these fears, explaining that he’s “hesitant to go to the doctor’s office on the simple fact that I would say a lot of people that have COVID would essentially end up being there.”[15] Even though New York’s test positivity rate at this point was well below 5 percent, these hesitancies persist.

While the fear of contracting COVID from a doctor’s office was the main deterring factor among those interviewed, a few discussed other reasons for this hesitancy. Ashley, a 20-year-old University student from Jamaica, Queens, explained that visiting the doctor was “definitely not something I’m going out of my way to get done now. I’m for sure a lot more wary of going to the doctor now…my hesitancy doesn’t actually come from me like ‘I’m gonna go to the doctor and contract the coronavirus because I feel like I’m more likely to contract the coronavirus at a supermarket than the doctor. My hesitancy basically comes from more like ‘I don’t want to add to the overburdened healthcare system if I myself was not sic challenges a common assumption that all hesitancy against healthcare during the coronavirus is connected to a fear of contagion.

Ronnie, a 26-year-old from Brooklyn, highlighted another dimension of the evolving relationship with healthcare he has witnessed in the Afro-Caribbean community. Ronnie remarked on the disproportionate economic impact on his community, noting that the hesitancy is not just related to the biological virus, but also to its economic devastation, claiming, “I don’t know if [the coronavirus itself] made them less willing to go to a doctor, but I think it took away access for some because jobs may have come with healthcare services that without jobs they could not afford.”[17] For some, access has become a deterring factor rather than just viral anxiety.

While there certainly was some hesitancy present about seeking out healthcare (more so in the hospital setting than the outpatient setting) during August 2020 when these interviews were conducted, a strong majority of interviewees expressed a willingness to schedule a visit with their primary care provider. Many interviewees shared how their anxieties about healthcare have shifted throughout the course of the pandemic in New York City, expressing significant hesitancy in the peak of the pandemic in March and April, but by summer 2020, as case numbers had significantly declined and the healthcare system was better able to manage cases of the virus, interviewees often discussed how they were much more comfortable.

Robert explained that if he needed to schedule an appointment, he would do so, but would probably delay scheduling his annual physical, reserving visits for more acute or chronic healthcare matters. Robert calmly explained to me that “I don’t think I would be as much scared as I was before due to the fact I was not that knowledgeable about the virus. So for now, mentally I am not too scared, but I think going in there I should be seeing differences, which would make me more comfortable. If need be, I will go.”[18]

This idea of “seeing differences” in the outpatient setting was a common sentiment observed among interviewees, many of whom felt comfort and assurances in enhanced social distancing and hygienic practices implemented in providers’ offices. Sharon added that “I am not afraid about going to the doctor right now for my yearly checkup because I went to that office with someone and they’re taking all the necessary precautions.”[19]

Veronica, a middle aged woman from Jamaica living in the Flatbush, Brooklyn area, also detailed how current social distancing precautions have eased her anxieties about visiting the doctor. Veronica shared, “I’d go to the doctor now. I can tell you when I go there I see they are trying to be careful. Before when I went there the waiting room used to be all full, and now it’s only two people at a time for the appointment. I feel quite comfortable going there because when you go, they stop you at the entrance and you have to get your temperature taken.”[20]

Overall, among these interviewed members of the Afro-Caribbean community in New York, there was not a current strong hesitancy to access their primary care providers, as many expressed confidence in the newly implemented infection control precautions. Yet, this level of comfort was not universal among all members of the Afro-Caribbean community, as some fears about the healthcare environment still lingered from the peak of the chaotic peak of the pandemic in March and April.

A DEEPENING DISTRUST IN HEALTHCARE

However, while the pandemic may not have dramatically changed these communities’ willingness to access healthcare, many interviews reflected a more long standing distrust of their local medical system due to the historically subpar medical care concentrated in predominantly Black and Latino New York neighborhoods. Entangled in legacies of inequality and structural injustices, the interviews exposed a complex relationship between the local healthcare system and the Afro-Caribbean community that was already weakened, and even antagonistic in some instances, prior to the COVID-19 pandemic — an event that only exacerbated a common and historically ingrained distrust in the healthcare system among the Afro-Caribbean community. Frequently in the media and medical discourse, there is a binary discussion of outpatient care prior to COVID-19 and post-COVID-19, identifying the pandemic as a differentiating factor in people’s willingness and ability to seek healthcare services. Yet through these oral histories, it becomes clear that this binary is not applicable to many in Afro-Caribbean communities, as a distrust and hesitancy around healthcare systems persisted before the pandemic, just as racial inequalities in healthcare and legacies of medical racism persisted.

In my conversation with Darryl, he encapsulated the strained relationship between healthcare and Black communities.

“In terms of not wanting to seek health professionals because as far as the statistics, a lot of Black folks are more negatively affected by health professionals and with this new corona thing…so the fact there was already a fear of doctors from the beginning and that there’s now a disease that’s disproportionately hurting Black and brown folks…now it’s just like ‘all right, we know not to go to you guys.” [21]

While some of the people I interviewed did not feel as though there were specific instances in their interactions with healthcare professionals where they received suboptimal care because of their race, there still seemed to be a significant sentiment of how the healthcare system, from a more systemic perspective, disproportionately underserves communities of color (which has been thoroughly documented in academic research).[22] Darryl further explained that “it’s one of those things where you know about it but your situation is different. It’s kind of like racism — you know racism exists but I haven’t experienced a lot of personal racism. Now I’ve experienced racism, but not on a strong effect on a daily basis.”

Veronica reiterated similar struggles as a Black woman, poignantly referencing the inequalities in healthcare the Black community faces. “I come to realize that most of the time with color, you don’t get the best of care, you don’t get the best of care, you don’t get 100 percent. That’s why I always have my private doctor that I go to..I think that when you have a primary care doctor, you are really better cared for than when you go into the hospital.” Veronica explained that the more individualized care she receives from her primary care provider makes her feel as though she is getting better quality of care, where she is not just perceived as “another Black woman” in the more depersonalized hospital setting, reflecting the persistence of racism and prejudice and healthcare. Veronica later noted how she felt many of the doctors in the hospital try to take advantage of patients with good insurance, claiming that “everybody’s running to take care of you when you have good medical coverage…it’s the first thing they ask you… and it shouldn’t be like that.” [24]

Darryl continued to discuss how the historical mistreatment, medical experimentation and scientific racism targeted towards Black and other marginalized communities have cultivated a distrust of healthcare officials within the Black community. “I know about issues within the healthcare system. I know about a lot of Black moms that have complicated births, I know about a lot of historic issues from Tuskegee syphilis trials to little experimentations that still go on today. So I have the knowledge of things that have happened in the Black community.”[25]

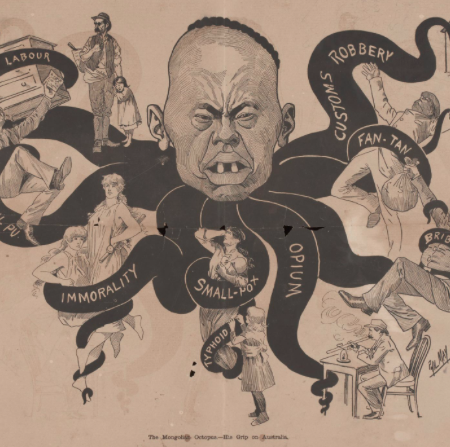

The Black community has faced centuries of medical injustice, where medical and scientific authorities have exploited their bodies for experimentation, manipulated science to justify their supposed inferiority and have provided them with subpar medical care — disparities which have evolved into the healthcare inequities predominant today. For instance, J. Marion Sims, who is considered one of the founders of gynecology, brutally experimented on his African American slaves, for the purpose of “scientific progress.”[26] Prevailing theories of biological determinism and other forms of medical racism in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries supported ideas that Blacks were “immune” to pain (justifying brutal slavery practices) and physiologically inferior to whites. The Tuskegee Syphilis study is another notorious example of the medical subjugation of Black persons in this country. The United States Public Health Service oversaw this study, which recruited a group of Black men in rural Alabama in 1932 with latent syphilis and monitored these men to examine the effects of untreated syphilis on the body, not informing them of their diagnosis or providing treatment that could have saved their lives, despite the availability of effective treatment at the time. An egregious ethical transgression and exploitation of Black bodies, the United States government enabled this study to continue for 40 years, until 1972.

This subpar healthcare provided to Black communities is still prevalent today, evidenced by the countless instances of healthcare disparities between Blacks and whites and a persistence of racism and bias in the medical profession. For instance, the maternal mortality rate in the United States for Black women is greater than three times the maternal mortality rate for white women and the infant mortality rate for Blacks is more than double that of whites.[27] Blacks have higher rates of diabetes, hypertension and heart disease, Black men have one of the lowest average life expectancies and Black children are 500% more likely to die from asthma than their white counterparts.[28] A 2015 study in the American Journal of Public Health, which administered implicit association tests to health care providers, found that the majority of providers surveyed demonstrated positive biases towards white populations and negative biases towards Blacks.[29] Additionally, a 2016 study in Proceedings of the National Academy of Science disturbingly found that approximately half of the sample of white medical students and residents believed there were biological differences between Blacks and whites that make Black people less sensitive and perceptive to pain — a physiologically false idea that derives from nineteenth century biologically determinist theories of Blacks’ biological inferiority.[30]

In response to the disproportionately subpar healthcare concentrated in predominantly Back communities, many of the interviewees explained that they often left their own neighborhoods to seek healthcare providers in generally whiter and wealthier areas. Darryl told me that “I don’t go to health professionals in my local area…most of my healthcare providers are in white neighborhoods, so I’ve been fortunate to have the “good” [quote on quote] medical care…and even if I have to come out of pocket… I go to extreme lengths to get the best healthcare I can get myself.” [31]

Ashley, who belongs to a predominantly Afro-Caribbean church in the Northeast Bronx, explained that the majority of her friends and family will drive out of state to Long Island or Connecticut (generally wealthier areas) to seek medical care, referencing a family friend of hers who contracted coronavirus and drove all the way to Greenwich, Connecticut, “because they knew that he would have a better chance of being seen than if he were in a hospital in New York.”[32] This “border crossing” outside of the inner city was not just unique to coronavirus, but something that people in her community were accustomed to doing prior to the pandemic.

As reflected in many interviews, the biological agent of the novel coronavirus magnified a sense of anxiety and uncertainty around the healthcare setting, presenting the locale as dangerous to their health. Yet, what emerges from Ashley’s comment is a pressing sense of the preexisting threat and spatial inequities of healthcare — a more long standing distrust of the medical institutions located in their neighborhoods due to a common perception in her community that these hospitals provided lower quality care than those in white areas. These pervasive inequalities motivate a literal and figurative “border crossing,” where some in the Afro-Caribbean communities have historically left their neighborhoods to seek medical care, as their local institutions were perceived as a potential threat to their own health. As the coronavirus pandemic escalated in March, this perception of the hospital as dangerous and a “potential threat to their own health” was only amplified, but now to a much more widespread and visible extent.

DISPARITIES IN NEW YORK CITY HOSPITALS

However, this inequality between hospitals is not just differentiated by hospitals within the city and those in the suburbs. There are pervasive inequalities within the New York city hospitals themselves. These discrepancies are often fueled by race and income, where private hospitals that are part of large academic networks are generally located in whiter and wealthier areas, while public hospitals and local private (independent facilities which often struggle with underfunding) are located in poorer neighborhoods of communities of color. These inequalities received a lot of media attention during the pandemic, where many public hospitals were overwhelmed (considering the pandemic also disproportionately affected communities of color) and had fewer resources. The rekindling of the Black Lives Matter movement this summer and it’s expansion of racial and social justice discourse on a national scale have helped raise greater awareness of these structural injustices and racial inequalities in health care — especially those in the coronavirus. However, these inequities and awarenesses of them in Black communities have existed long before the coronavirus pandemic.

Ashley offered a particularly poignant anecdote about the lower quality of care offered in communities of color. She said that several years ago a family friend “had a stroke and he was brought to a hospital in Brooklyn and there was no neurologist available there, so he essentially just got worse being in that hospital, so they were finally able to transfer him to New York-Presbyterian on the Upper East Side and he got better, not as quickly…he would have gotten better so much faster if he had got there first, because the other hospital is just really terrible. And his mom was really stressed out because she was like ‘I heard that [the Brooklyn hospital] was a hospital where everyone who goes there dies.’” [33] One individual claimed “It’s always been known that these institutions are subpar compared to private institutions.” [34]

The perspective of the inequalities between hospitals is not just limited to regular people in the community, but has also been a part of reality for many in the healthcare industry. Ariana, a 25-year-old whose family is Jamaican, was working as an ICU technician during the pandemic at a major, private academic hospital in Manhattan. Ariana discussed the glaring differences between her hospital and the many overwhelmed public institutions:

“It was just like a tale of two cities kind of thing. Just like Manhattan was really empty because most wealthy people fled to other areas, it’s kind of the same way with hospitals. Like we were inundated with patients, but I would watch the news and read the newspaper and see Elmhurst and I was like ‘what the hell, I thought we had it bad, but that was really bad.’ I think that it’s unsurprising and that’s unfortunate, but I think this why people really choose private institutions.” [35]

Ariana referenced the ‘horror’ stories that were circulating in the news about some of these lower quality hospitals in predominantly Black neighborhoods during the pandemic. “Look at the neighborhoods these hospitals are in and the care they’re receiving. I saw a video on Facebook that was shot at Brookdale and the guy had not had his bedpan changed for two days. There was a story about a nurse at Brookdale and they didn’t want to touch her when she was a patient herself, and she was pregnant and they told her to change her own IV herself because she’s a nurse.” [36] This disturbing story is a striking example of the narratives which propel distrust in local medical centers within the Afro-Caribbean community. The local hospital here is perceived as unsafe and even consciously endangering the life of their patient, often due to insufficient resources. In a medical system that has nurtured the unequal health outcomes between Blacks and whites and has overseen centuries of inadequate treatment, memorable and jarring stories like these reinforce the perception that the healthcare systems concentrated in Black neighborhoods are often not equipped to safeguard health.

The patchwork of hospital networks that make up New York City’s hospital system has cultivated in a scattered healthcare system with vast inequities, leading to significant disparities in care and access, especially for low-resource populations. Private and academic medical systems are generally well endowed and located in predominantly white and wealthy areas of Manhattan. Public hospitals (run by the city government) and independent private community hospitals (as well as satellite campuses of academic medical systems, which generally do not have the same resource capital as their flagship locations in Manhattan) are concentrated in the outer boroughs, especially in predominantly Black and Latino and low-income neighborhoods.

These public and community hospitals (“safety-net hospitals”) treat more residents on Medicaid or Medicare, or without insurance, and their resources pale in comparison to the funding of private medical centers a few miles away in Manhattan.[37] In fact, a New York Times investigation documented that during the coronavirus pandemic the COVID-19 death rate in some safety-net hospitals was three times higher than that of their wealthier counterparts in Manhattan. Patients at private academic hospitals in Manhattan received access to experimental drugs like Remdesivir and other expensive, yet life-saving, technologies like heart-lung bypass machines, while safety-net hospitals in the outer boroughs often did not have enough staff to monitor critically ill patients, which even led to unnecessary and tragic deaths among some patients, who removed oxygen masks going to the bathroom or extubated themselves in the confusion of emerging from a coma, as they were left unsupervised for extended periods of time due to insufficient staffing. Access to clinical trials and functional ventilators were challenges for safety-net hospitals.[38] While the understaffing of safety-net hospitals received more attention during the pandemic, the large patient-to-staff ratios at these facilities has been a more long standing issue that has contributed to limitations on high quality care. There is a complicated legal and financial history that has facilitated a dramatic escalation of these disparities — where geography now becomes a determinant of life or death, as resources continue to expand for the private networks and safety-net hospitals struggle to meet the basic medical needs of their population, which is a crisis that is also compounded by the socioeconomic inequities between the populations served.

The table included from a report from the Community Service Society, a non-profit aimed at fighting poverty in New York, exemplifies both the institutional disparities and the outer boroughs’ disproportionate COVID-19 case count.[39]

Manhattan has a significantly larger amount of beds per 1,000 residents (6.4) than the outer boroughs, which have an average of 2.2 beds per 1,000 residents. It is no wonder why a hospital equipped to treat a greater proportion of its population would fare better in a pandemic than a hospital that has nearly a third of the capacity. Furthermore, these outer boroughs had higher recorded COVID-19 cases than Manhattan, with the outer boroughs averaging around 23 COVID-19 cases per 1,000 people and Manhattan having 12 cases per 1,000 people. While the disparities in case counts can be correlated with socioeconomic and demographic disparities between the two regions, it is still striking how the hospitals with the most relative capacity had the smallest surrounding COVID-19 case burden, while those with the most constrained resources had a much larger burden.

In evaluating the spatial inequalities of healthcare in New York City, I constructed this map, which depicts all of the hospitals in the city, color coding their location markers by their Medicare 5-star quality rating (with higher stars indicating better performance).[40] Looking at the areas highlighted in orange (predominantly Black ZIP codes) and blue (predominantly Hispanic zip codes), nearly all the medical facilities in those areas are one-star quality hospitals. However, nearly every hospital with three or more stars were located in the white and wealthy neighborhoods of Manhattan (except for two facilities in Brooklyn, which were satellite facilities of private academic medical centers in Manhattan and were not differentiated in the rating data).

Reconnecting this to the issue of mistrust of local institutions in Afro-Caribbean communities, this very visible and tangible disparity further confirms community beliefs of the lower quality healthcare in their neighborhoods and pushes some to cross these borders to access healthcare facilities in Manhattan that have greater resources and capabilities.

Ariana remarked that this disparity has always been present, but the devastating impact of the coronavirus and the media coverage that followed it truly exacerbated and exposed many of these disparities that disproportionately target people of color.

“This is where the situation is amplified. This is why the attitudes were the way things were before they happened because normally people say, ‘if you want to die, you go to Kings County or you go to Brookdale’ and before it was more of a joking kind of thing and now it really wasn’t a joke.”[41]

CONCLUSION

COVID-19 is inherently complicated — a compounding set of social phenomena unleashed and exacerbated by a microscopic biological agent. Yet, as witnessed, the coronavirus pandemic has exploited many pre-existing and endemic inequalities, targeting historically marginalized communities, like the Afro-Caribbean communities I interviewed and the larger Black, Latino and low-income populations of New York City’s outer boroughs. These same populations have often been left out of historical narratives, or solely reduced to “the other,” underscoring the importance of oral histories in documenting their complex and socially and historically influenced perspectives — something which is critical to engage with in order to expand comprehensions of how the coronavirus affects people of color and low-resource communities. Voices matter. In the midst of the pandemic that has threatened to deepen and exacerbate the pre-existing socioeconomic and healthcare inequalities experienced by many Blacks and Latinos in the United States, their voices necessitate unprecedented amplification.

These interviews within the Afro-Caribbean community emphasize the importance of personal experiences and reflections in health studies, as their perspectives provide invaluable insights into how the pandemic is experienced in “real life,” since these communities who have been so significantly afflicted are still comprised of individual people, not just statistical outliers. Furthermore, these interviews have complicated a commonplace discussion of COVID-19 as a binary phenomenon — life before and after COVID-19. Through disentangling the perceptions and meanings of these communities’ engagement with the healthcare system, it became apparent that there was a much more long standing distrust and skepticism of local healthcare providers due to the healthcare inequities deriving from histories of racism, socioeconomic suppression and poor medical treatment. Here, examining the pre-existing hesitancies around healthcare providers through personal interviews provided a perspective which graphs contrasting healthcare visits prior to COVID-19 and post-COVID-19 could never genuinely encapsulate.

The scientific and medical knowledge of the coronavirus, as well as its economic and social consequences, some days may seem to be constantly changing and fluctuating, culminating in a societal focus on the “present” and empirical aspects of the virus. Daily updates on confirmed case counts and rising deaths, stock market rises and drops, increasingly politicized infection control measures, detailed vaccine developments. Many often look to these tangible representations of the progress and the effects of the pandemic to attempt to understand their changing environments. However, as previously discussed, these numbers and news headlines have their own limitations. To more complexly and deeply comprehend the pandemic, it needs to be situated in its historical context. While comparisons to the influenza pandemic of 1918 may be constructive, other historical narratives deserve consideration as well. The histories of the unjust plight of Black communities in the United States, medical racism, legacies of exploitation, mistreatment and disparities maintained by the healthcare system over centuries, and even local narratives of how socioeconomic divisions and politics cultivated in a hospital system that is so broken. These narratives merit just as much evaluation as those of the 1918 influenza pandemic or HIV/AIDS in the 1980s in the United States, as medical and racial inequalities manifest themselves in a more metaphorical epidemic that has lasted for centuries.

While the geographical scope of this project is mostly local, the perspectives documented in these interviews have a sort of international application. These experiences and testaments to inherent inequalities in the healthcare system fit into a more global narrative of the coronavirus, as a disease that has been somewhat of a global equalizer — infecting individuals in nearly every country — while also serving as a force of division, further exacerbating endemic inequalities. The struggle to access high quality healthcare within these New York Afro-Caribbean communities is solely a microcosm of a global pattern of low-income and ethnic minority populations having subpar healthcare resources. The interviewees in this project engage in a literal and figurative form of “border crossing.” In the geographical sense, many in the communities feel compelled to leave their neighborhoods for higher-resource areas in search of better quality healthcare, and in a wider metaphorical sense, these individuals must traverse the deepening borders and limitations of systemic inequalities that plague low-income and minority communities.

For privacy purposes, all interviewees are referred to by pseudonyms. Thank you to all who gave their time and perspectives in these interviews.

SOURCES

[1] Dennis Slattery, Dave Goldiner and Chris Sommerfeldt, “Gov. Cuomo Places New York on ‘Pause’ As Coronavirus Cases Soar Above 8,500,” New York Daily News (New York, NY), Mar. 20, 2020. https://www.nydailynews.com/coronavirus/ny-coronavirus-20200320-hiya77j3w5brjbt7lbkrvcmeve-story.html

[2]“Covid-19: Data; Cases, Hospitalizations, & Deaths,” New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene, accessed Sept. 10, 2020. https://www1.nyc.gov/site/doh/covid/covid-19-data.page

[3] Ariana, interview by the author, August 18, 2020, New York, NY.

[4] Molla S. Donaldson, Karl D. Yordy, Kathleen N. Lohr et al, “Value of Primary Care,” in Primary Care: America’s Health in a New Era, ed. Committee on the Future of Primary Care, Institute of Medicine (Washington D.C., National Academies Press, 1996).

[5]Ateev Mehotra, Michael Chernew, David Linetsky, et al, “The Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Outpatient Visits: Practices are Adapting to the New Normal,” The Commonwealth Fund, accessed Sept. 10, 2020. https://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/2020/jun/impact-covid-19-pandemic-outpatient-visits-practices-adapting-new-normal

[6]Maria Caspani and Jonathan Allen, “Coronavirus Deadliest in New York City’s Black and Latino Neighborhoods, Data Shows,” Reuters (New York, NY), May 18, 2020. https://www.reuters.com/article/us-health-coronavirus-new-york-deaths/coronavirus-deadliest-in-new-york-citys-black-and-latino-neighborhoods-data-shows-idUSKBN22U32A

[7] The data did not differentiate between Hispanic Latinos and non-Hispanic Latinos

[8] Jeffery C. Mays and Andy Newman, “Virus is Twice as Deadly for Black and Latino People than Whites in N.Y.C.,” The New York Times (New York, NY), Apr. 8, 2020. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/04/08/nyregion/coronavirus-race-deaths.html

[9] Ibid. The data referring to minorities making up a higher proportion of essential workers did not further break down the data by race.

[10] Darryl, interview by the author, August 1, 2020, New York, NY.

[11] Robert, interview by the author, July 22, 2020, New York, NY.

[12] Ibid.

[13] Sharon, interview by the author, July 22, 2020, New York, NY.

[14] Robert, interview by the author, July 22, 2020, New York, NY.

[15] Darryl, interview by the author, August 1, 2020, New York, NY.

[16] Ashley, interview by the author, July 31, 2020, New York, NY.

[17] Ronnie, interview by the author, August 19, 2020, New York, NY.

[18] Robert, interview by the author, July 22, 2020, New York, NY.

[19] Sharon, interview by the author, July 22, 2020, New York, NY.

[20] Veronica, interview by the author, August 18 2020, New York, NY.

[21] Darryl, interview by the author, August 1, 2020, New York, NY.

[22] Jamila Taylor, “Racism, Inequality and Healthcare for African Americans,” The Century Foundation, Dec. 19, 2019. https://tcf.org/content/report/racism-inequality-health-care-african-americans/?session=1

[23] Darryl, interview by the author, August 1, 2020, New York, NY.

[24] Veronica, interview by the author, August 18 2020, New York, NY.

[25] Darryl, interview by the author, August 1, 2020, New York, NY.

[26] Keith Wailoo, “Historical Aspects of Race and Medicine: The Case of J. Marion Sims,” JAMA 320, no.15 (2018): 1529.

[27] Jamila Taylor, “Racism, Inequality and Healthcare for African Americans,” The Century Foundation, Dec. 19, 2019. https://tcf.org/content/report/racism-inequality-health-care-african-americans/?session=1

[28] “Health Disparities Between Blacks and Whites Run Deep,” Harvard T. H. Chan School of Public Health, accessed Sept. 10, 2020. https://www.hsph.harvard.edu/news/hsph-in-the-news/health-disparities-between-blacks-and-whites-run-deep/

[29] William J. Hall, Mimi V. Chapman, Kent M. Lee, et al, “Implicit Racial/Ethnic Bias Among Health Care Professionals and Its Influence on Healthcare Outcomes: A Systematic Review,” American Journal of Public Health 105, no.12 (2015). doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2015.302903.

[30] Kelly M. Hoffman, Sophie Trawalter, Jordan R. Axt, et al., “Racial Bias in Pain Assessment and Treatment Recommendations, and False Beliefs About Biological Differences Between Black and Whites,” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 113, no.16 (2016): 4296-4301

[31] Darryl, interview by the author, August 1, 2020, New York, NY.

[32] Ashley, interview by the author, July 31, 2020, New York, NY.

[33] Ibid.

[34] Ariana, interview by the author, August 18, 2020, New York, NY.

[35] Ibid.

[36] Ibid.

[37] Brian M. Rosenthal, Joseph Goldstein, Sharon Otterman et al., “Why Surviving the Virus Might Come Down to Which Hospital Admits You,” The New York Times, July 1, 2020. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/07/01/nyregion/Coronavirus-hospitals.html

[38] Ibid.

[39] Amanda Dunker and Elisabeth Ryden Benjamin, “How Structural Inequalities in New York’s Health Care System Exacerbate Health Disparities During the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Call for Equitable Reform,” Community Service Society, June 4, 2020. https://www.cssny.org/news/entry/structural-inequalities-in-new-yorks-health-care-system

[40] Medicare 5-star quality ratings are developed by Medicare (administered by the U.S. federal government) and represent a facility’s overall quality, combining a variety of quality measures. Larger amounts of stars correspond to higher quality ratings. The types of measures considered in developing this rating include statistics relating to mortality, safety of care, readmission, patient experience, effectiveness of care, timeliness of care, and efficient use of medical imaging.

[41] Ariana, interview by the author, August 18, 2020, New York, NY.